Gordon Parks was working as a porter for the Northern Pacific Railroad when he bought his first camera, a used Voigtlander Brilliant, at a pawnshop in 1937. Teaching himself to use the device, Parks quickly established his talent and range, shooting everything from fashion photographs to images of people living in poverty in Chicago’s South Side – images that, in his words, ‘convinced me that even the cheap camera I had bought was capable of making a serious comment on the human condition’. They convinced others, too, landing him a fellowship as a photographer documenting the work of the Farm Security Administration in 1942. Six years later, Parks made history as the first African American staff photographer and writer at Life, a position that he secured with a nuanced photo-essay on the teenaged Harlem gang leader Red Jackson. Parks would remain at Life for more than two decades, during which time he also adapted his semi-autobiographical novel The Learning Tree into a movie, making him the first African American director of a film for a major studio.

A number of photographs by Parks, many of which were made on assignment for Life, are currently on view in New York, at MoMA and at Jack Shainman Gallery. Coming on the heels of a two-part show of Parks’s work at Alison Jacques Gallery in London in the summer and autumn of 2020, this double bill suggests a recasting of his oeuvre as not only photojournalistic but also artistic. Both of these displays show how Parks took on the project of representing the realities of Black experience during the struggle for civil rights in the US – ‘bearing witness’, as Jelani Cobb puts it in an elegant short essay for the exhibition at Jack Shainman. He did so with the knowledge that he was also putting the stark realities of racial injustices before Life’s vast – predominantly white and middle class, frequently suburban – readership.

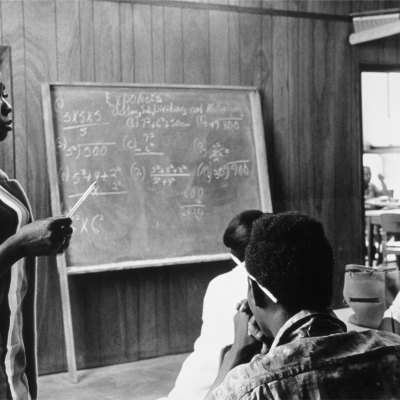

Untitled, Mobile, Alabama (1956), Gordon Parks. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © the Gordon Parks Foundation

At MoMA, the qualities of acuity and empathy that Parks brought to his depictions of urban crime are on full display. Mounted in November as part of the museum’s initiative to seasonally rotate a portion of the works in its permanent collection galleries (and featuring works that entered the museum’s collection last year), ‘Gordon Parks and the Atmosphere of Crime’ features images of crime scenes, police precincts, and prisons that Parks captured for a photo-essay published in Life in 1957. The images were to accompany the first instalment in a six-part series on the perceived growth of crime in US cities – a perception that, as Nicole R. Fleetwood points out in an essay in an accompanying catalogue published by Steidl, was tied up with white anxiety around demographic shifts as Black Americans fled the racial terrorism that pervaded the rural South. In the writings featured in the splashy exposé, Life’s editors largely failed to complicate or challenge misperceptions surrounding crime, though journalist Robert Wallace did note the inaccuracies of crime statistics.

Clustered on the wall at MoMA, the ‘Atmosphere of Crime’ prints are divorced from the words and cropping – and thus to an extent, the problematic framing – supplied by the magazine’s reporters and editors. Contrary to the convention of shooting crime photographs in black and white with a powerful flash, Parks opted to use colour slide film, making images that were soft and grainy with none of the harshness or implicit revelation of a flash bulb. In lieu of dictating what a criminal or a crime might be, he documented the processes of criminalisation. We see a pair of detectives on a raid, breaking down a door in a narrow, dingy hallway; a cop bent over a desk covered in papers, performing administrative duties; and a heavily populated prison with a vanishing point that makes its capacity appear endless – which, as part of the massive, seemingly indefatigable prison-industrial complex, it is.

American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942), Gordon Parks. Courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © the Gordon Parks Foundation

Fifty-eight photos by Parks, a mix of colourful archival pigment prints (he attains an inimitable celadon) and silver gelatin prints, span Jack Shainman’s two Chelsea exhibition spaces in ‘Gordon Parks: Half and the Whole’ (until 20 February). Parks made the photos across two decades; the earliest, shot in 1942 when he was working with the Farm Security Administration, is a clear-eyed portrait of an office-cleaning woman named Ella Watson that riffs on Grant Wood’s American Gothic – part of a larger project in which Parks documented Watson and her community over the course of four months. The photos in this exhibition are loosely grouped by series, with examples from notable bodies of work such as ‘Invisible Man’ (1952), a collaboration with novelist Ralph Ellison in Harlem; ‘Segregation in the South’ (1956), which documented the Jim Crow era in Mobile, Alabama in full colour; ‘The Atmosphere of Crime’ (1957), forming some overlap with the MoMA presentation; ‘How It Feels to Be Black’ (1963), dreamlike pictures from Park’s hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas; and ‘Black Muslims’ (1963), which chronicled the growing Nation of Islam movement and its key figures such as Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad.

Many of the photographs in ‘Black Muslims’ depict scenes of protest. On 27 April 1962, the Los Angeles police force raided a Nation of Islam mosque, shooting seven unarmed Muslims including William Rogers, who was paralysed for life, and Malcolm X’s close friend Ronald Stokes, who died. An all-white coroner’s jury went on to rule Stokes’s murder to be ‘justifiable’. Protests and rallies erupted in response. ‘WE ARE LIVING IN A POLICE STATE’ reads a protester’s placard in a photo by Parks. In another image, this time with a police officer meeting the camera’s gaze, a demonstrator holds a poster proclaiming: ‘POLICE BRUTALITY MUST GO’. The line of protesters bearing signs behind him goes on and on, past the edges of the frame and into the here and now.

‘Gordon Parks: Half and Whole’ is at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, until 20 February. ‘Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.