From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Is it having to wear a mask or the art itself that makes ‘Grief and Grievance’ at the New Museum such an exhausting show? After a couple of hours, it’s hard to breathe. Judging by the number of visitors dabbing at their eyes, it’s hard not to cry too. Subtitled ‘Art and Mourning in America’, the exhibition was conceived by Okwui Enwezor as a response to Donald Trump’s ugly rhetoric around race, what the Nigerian-born curator believed was not just an indifference to Black American grief but a weaponisation of white grievance. More melancholy: Enwezor died in 2019; the show has been brought to completion by the New Museum’s artistic director Massimiliano Gioni working with artist Glenn Ligon and curators Mark Nash and Naomi Beckwith.

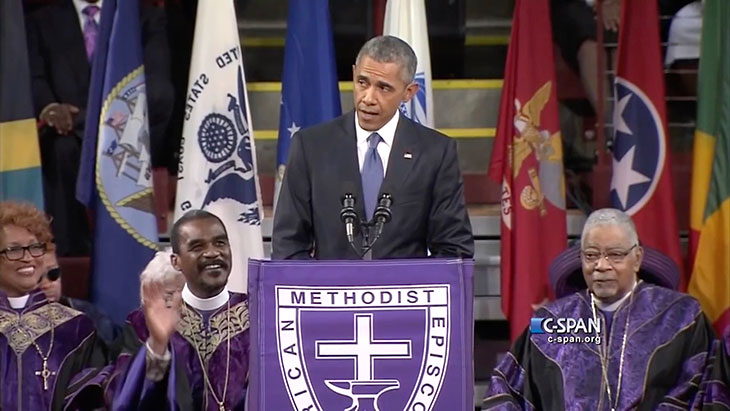

Thematic shows are risky enterprises. They risk turning art into theoretical fodder, mere illustration for critical arguments. (It’s striking that the essays in the exhibition’s handsome catalogue are mostly written by non-art historians such as Claudia Rankine and Ta-Nehisi Coates.) Still, there’s significant work here. Arthur Jafa’s Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016) is a tidal wave of a video made up of clips extracted from sources including rolling news, genre movies, sporting events and social media. Soundtracked by Kanye West’s ‘Ultralight Beam’, the images tumble and teem: a 17-year-old Notorious B.I.G. rapping on the streets of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn; Barack Obama singing ‘Amazing Grace’; LeBron James soaring and slamdunking. Many images are of Black Americans being harried, hosed, yelled at, shot in the back. Their movements are constantly restricted or regulated. To move without permission seems to be a crime.

Still from Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), Arthur Jafa. Courtesy the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels

And yet they rebel: lovers sway in private communion, Muhammad Ali avoids punches with balletic poise, churchgoers are possessed by the Holy Spirit. This is limbic resistance, motion and emotion, kinetic liberation. The clips are sometimes upsetting; sometimes – as when they’re taken from horror flicks such as Cloverfield – befuddling. For Jafa, the atmospheric pressure for Black Americans is so punitive and asphyxiating that even walking straight is an epic achievement. Love Is The Message may be too dizzying for some viewers, its quick cutting inducing image exhaustion, but its editing has real power and its juxtapositions radiate joyous, uncrushable energy.

More becalmed but at least as reverberative is The Birmingham Project (2012) by Dawoud Bey. Its name refers to Birmingham, Alabama, a city which, in the decades after the Second World War, was targeted by the Ku Klux Klan and became so combustible it was nicknamed ‘Bombingham’. In 1963 a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church killed four Black girls. Two Black teenage boys also died in the ensuing protests. None of their faces appear in Bey’s photographs. Instead, he has created a series of diptychs featuring current residents of Birmingham: in one half of each is seated a girl or boy of the same age as those killed in 1963; in the other half is a man or woman – the age those kids would be if they were alive today.

It’s a simple but beautifully executed idea. The individuals are photographed in religious or museum settings. The mood is quiet. Though they’re actors of sorts, it’s hard not to see the young ones as direct stand-ins for the fallen. We peer at their faces as we do those of the urchins and dreamers in Michael Apted’s Up series – with pity and with anxiety. The older sitters are phantasms: projections of who the kids might have become. Many Black American youths never do grow old – destroyed by poverty and toxic environments at least as much as they are by police violence.

Visitors stepping out of the lift for the New Museum’s second floor are immediately confronted by what seems at first glance to be a totalled, maybe firebombed car. This is Nari Ward’s sculpture Peace Keeper (1995) and the car, on closer inspection, is a hearse. It’s been smeared with grease that looks like tar and sits inside a cage that’s reminiscent of a prison cell, clumps of rusted metal pipes above, and dark and intimidating mufflers below. Move closer still, and there are feathers stuck to the vehicle. The work is mysterious, terrifying. It evokes both a crime scene and a salvage yard where there’s barely anything left to be salvaged.

Peace Keeper (1995) by Nari Ward (installation view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1995). Courtesy the artist, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul/Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Beijing, Les Moulins, and Havana

Ambient brutality is everywhere in the show. Melvin Edwards’ Lynch Fragments (1963–ongoing) – a wall-hung series of hooks and deformed chunks of metal – recalls the mechanical torture commonplace during plantation slavery. In the same room are Diamond Stingily’s Entryways, a series, begun in the mid 2010s, of wooden doors on which are propped menacing baseball bats. Artist and musician Terry Adkins is represented by his X-ray photographs of Southern memory jugs, drinking vessels to which spoons, bracelets and other affectionate knick-knacks are affixed as marks of attachment to the dead. Here they resemble forensic evidence, cold remnants of vanquished communities.

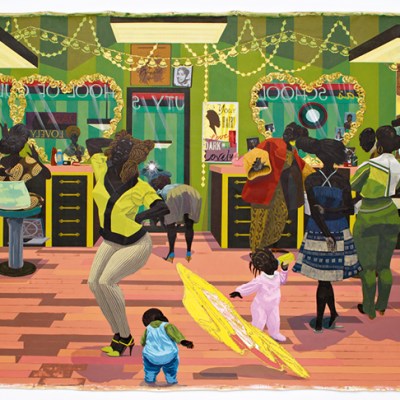

The show has its misfires. Carrie Mae Weems’s Constructing History series of 2008, in which she enlists art students to appear in staged presentations of mourning connected to the deaths of Black political leaders, resembles nothing so much as Sunday-supplement fashion spreads. Kerry James Marshall’s Souvenir IV (1998), a collaged banner of a domestic interior jazzed up with silver glitter and appropriated photos of Black entertainers, exemplifies rather than transcends the kitschy motifs it deploys. The hanging of Jack Whitten’s celebrated painting Birmingham (1964), made in the aftermath of the church bombing in 1963, is underwhelming, the work lost on the show’s top floor.

Birmingham (1964), Jack Whitten. Collection Joel Wachs. Courtesy the Jack Whitten Estate and Hauser & Wirth

As a cultural diagnosis ‘Grief and Grievance’ is unpersuasive, a sweeping threnody that doesn’t cede enough space to Black play, riddling and enchantment. In the time between its conception and staging, cities across America were taken over by Black people singing out – militantly rather than melancholically – for social change. And by millions of white people who were disavowing grievances or resentment. All of them were, in their exuberant and polyphonic fashions, contributing to a collective work of social art dedicated less to mourning than to the morning after.

‘Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America’ is at the New Museum, New York, until 6 June.

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.