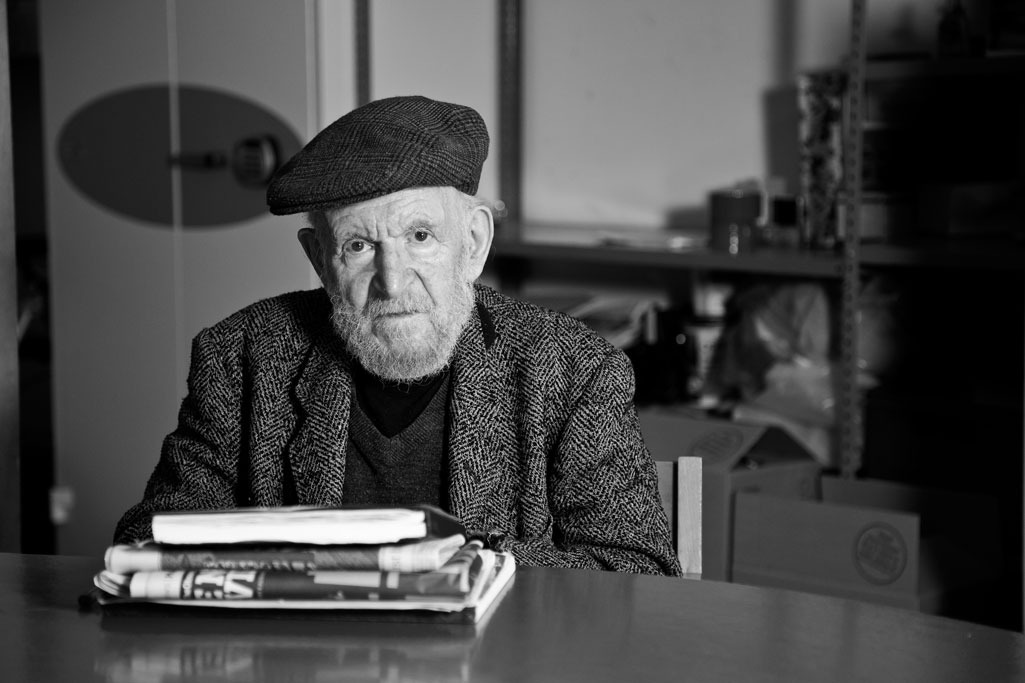

Gustav Metzger, the soft-spoken activist with a revolutionary art agenda, died last week at the age of 90. The pioneer of Auto-Destructive and Auto-Creative Art rejected the art world and invented the ‘art strike’, while his Historic Photographs series of installations are among the most powerful works to have born witness to the tumultuous history of the 20th century.

Metzger set an example that most of us would find hard to follow. John A. Walker, the British art critic and historian, called him the ‘conscience of the art world.’ He had a fierce integrity that led him to reject the capitalist infrastructure of the art world, costing him financial security and professional success. He made work that was ephemeral and unsaleable. He was a key precursor of activist art, devoting his energies to drawing attention to social and environmental issues. He spent much of his life a ‘stateless’ person. At times, he led a precarious existence.

Metzger was born in Nuremberg in 1926. He witnessed Kristallnacht first-hand, and lost most of his family to the Holocaust. In 1939, he escaped with his brother on the Kindertransport to England. During the war, he worked in a furniture factory in Leeds, becoming immersed in radical left-wing politics, while the work and writings of Eric Gill seeded the notion of becoming an artist. In 1945 he enrolled at the Borough School of Art in London, attending night classes with David Bomberg, a colourful, unconventional teacher with strong political beliefs who left a lasting impression on Metzger.

It was, however, his break with Bomberg in 1953 that proved pivotal for Metzger. He moved to King’s Lynn where he traded junk from a makeshift studio-warehouse on Queen Street and ran a second-hand bookstall on Cambridge market. Here, his campaigning activities (with the local CND and North End Protest groups) began to merge with his aesthetic concerns; in 1957 he organised a modest exhibition of religious relics, mutilated and defaced during a period of iconoclasm between the English Reformation in the 1530s and the Commonwealth of 1649–60. This exhibition established the dialectical dynamic that would remain central to Metzger’s artistic practice: a symbiotic relationship between destruction and creation.

It was in King’s Lynn that Metzger developed his first Auto-Destructive Art work, a form of action painting in which he daubed and sprayed acid onto a blank ‘canvas’ of synthetic nylon. As the acid dissolved the fabric, the painting destroyed itself. This heavily symbolic performance was repeated as a guerrilla intervention on the South Bank in July 1961, and became a powerful metaphor for the destructive systems of war and capitalism.

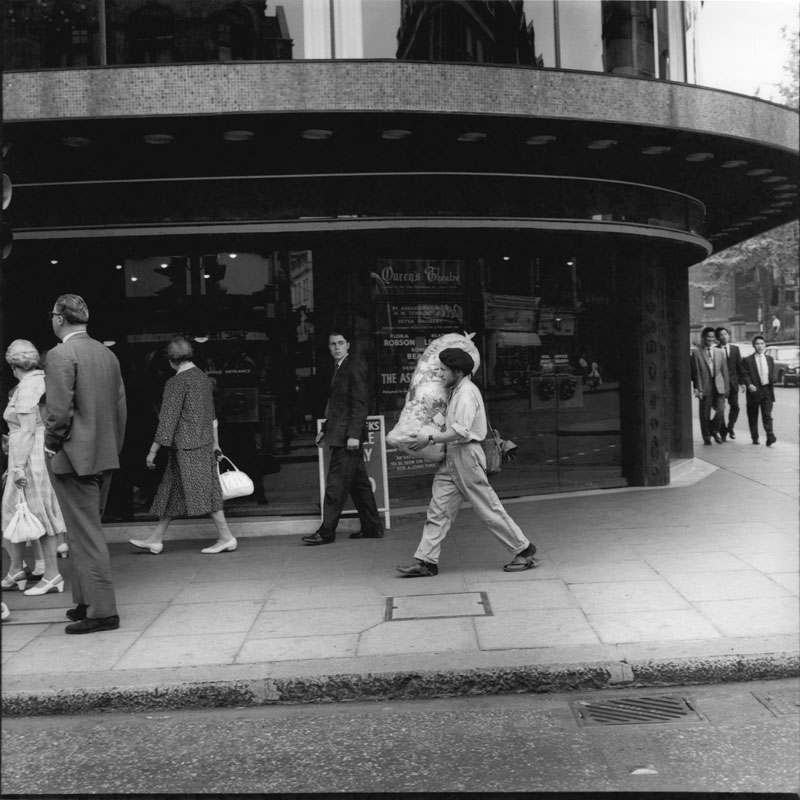

Gustav Metzger (1960), Ida Kar. The artist used to collect rubbish sacks from outside the fashion houses in Great Marlborough Street and showed them in his earliest lecture/demonstrations on auto-destructive art. © National Portrait Gallery, London

‘Auto-Destructive Art seeks to be an instrument for transforming people’s thoughts and feelings, not only about art, but wants to use art to change peoples’ relation to themselves and society’, Metzger told an audience assembled at the Architectural Association in 1965. Many of his proposals for Auto-Destructive Art, which he saw as ‘a form of public art for industrial societies,’ were hugely ambitious and technically complex, with prohibitive costs and practical implications that meant they remained largely unrealised. Nevertheless, he worked on these proposals, developing models in collaboration with architects, computer software engineers and others, over several years. Thanks to a recent resurgence of interest in Metzger’s art, the work Karba (originally proposed for Documenta V in 1972), was realised for his exhibition at Lund Konsthall in 2006, and Project Stockholm, June Phase I (originally conceived for the first UN conference on the environment in 1972) was staged at the Sharjah Biennial in 2007.

Metzger was a passionate peace activist and campaigner against nuclear weapons. He was a founding member of the Committee of 100, an anti-war group formed in 1960 that favoured mass non-violent resistance and civil disobedience as forms of protest. In 1961, a week before the 17 September demonstration, he was among the 32 members (who also included Bertrand Russell) who elected to go to prison rather than be ‘bound over’ by the courts in an effort to prevent them from attending the demonstration. He was also a committed environmentalist and a vegetarian since the 1940s. His contribution to Sculpture Projects Münster in 2007 was the RAF (Reduce Art Flights) poster campaign.

Although Metzger campaigned against air travel and cars, and resisted owning a telephone, he was not anti-technology or science; far from it. He was interested in its potential to inspire and make new forms of art that could broaden our perceptual horizons and enhance our understanding of the world. Metzger was an early advocate of creative exchange between art and science, and actively sought out scientists as collaborators, drawing on their expertise to develop innovative artistic forms and some of the earliest light projections in the UK (Metzger produced lightshows for The Who, Cream and The Move at a concert on New Year’s Eve, 1966). Perhaps the most well-known example of these artistic experiments is Liquid Crystal Environment (1965/2005), currently on display at Tate Britain. He developed the technique that enabled him to create this work with the protein chemist Arnold Feinstein in Cambridge in 1965.

Between 1969–72, Metzger was also the founding editor of PAGE, the bulletin of the Computer Arts Society. In this role, he worked to expose the relationship between the military and capitalism, and highlight the social and ethical implications of technology. He wrote papers on emerging computer technologies and developed a number of artworks using plotters and programming software. He also became heavily involved in the Art and Science and New Science working groups of the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science (BSSRS).

Metzger was an erudite art historian, highly knowledgeable on topics from Vermeer to automata, and a natural polemicist. He developed the iconoclastic lecture/demonstration in the early 1960s, prefiguring the evolution of the genre as a form of performance art. In 1966, he co-organised DIAS: the Destruction in Art Symposium, which caught the mood of the countercultural underground and mobilised artists across Europe and the US with performances from Yoko Ono, John Latham and Hermann Nitsch.

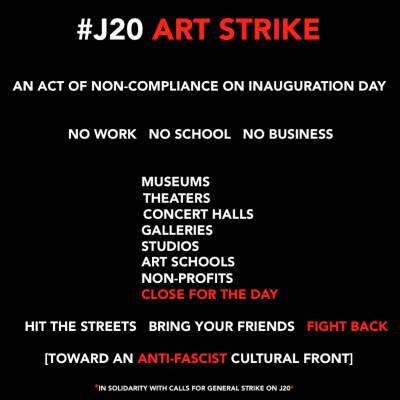

In the 1970s, Metzger became increasingly disillusioned with the art world. His contribution to the 1974 exhibition ‘Art into Society/Society into Art’ at the ICA, London, was to call for ‘Years without Art, 1977–80’. He left Britain to pursue research and curatorial projects in Germany and the Netherlands, returning to London in the early 1990s.

In 1998, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford organised the first UK survey of Metzger’s work. The exhibition marked the beginning of growing worldwide recognition of his unique contribution to 20th-century art. Retrospectives followed at the Generali Foundation in Vienna in 2005 and the Serpentine Gallery in 2009, while solo shows proliferated in New York, Mexico City, Warsaw, Nuremberg, Lyon and London. In 2014, he and I worked together on a show in Cambridge (where he had attended art school in the 1940s, and returned to twice in the 1960s to deliver lecture/demonstrations with titles such as ‘The Chemical Revolution in Art’).

Gustav Metzger believed in the responsibility of artists to inspire revolutionary social change. He never lost hope. Calling for a worldwide day of action to remember nature on 4 November, 2015, he said: ‘We appeal to arts professionals from all disciplines to take a stand against the ongoing erasure of species. It is our privilege and our duty to be at the forefront of the struggle. There is no choice but to follow the path of ethics into aesthetics.’

Elizabeth Fisher is an independent curator and writer based in the UK.