It seems incumbent on museum curators to confect a thesis for every exhibition. Those responsible for the exhibition of work by Gustave Caillebotte that recently opened at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris elected to focus on the Impressionist artist as a painter of men. It is a perfectly reasonable idea, especially since the impetus of the show was the recent acquisitions of two masterpieces with male subjects, Partie de bateau (Oarsman in a Top Hat) and Jeune homme à sa fenêtre (Young Man at his Window) by the Musée d’Orsay and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles respectively. (A third venue, the Art Institute of Chicago, contributes the artist’s masterpiece, the monumental Rue de Paris, temps de pluie.) Moreover, Caillebotte was unusual, if not unique, among his peers for frequently depicting the world of men.

Young Man at a Window (1876), Gustave Caillebotte. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

What is perplexing is the curators’ obsession with the painter’s sexual orientation. The wall texts and captions of this exhibition are loaded with the kind of euphemisms more familiar from the obituary pages of the Daily Telegraph. Gustave Caillebotte, we learn, was a bachelor who preferred the company of men, who desired to belong to a group, lived with his widowed mother and may well have had daddy issues. Most of the exhibits are interpreted through this prism, even though – as the same texts admit – there is no definitive proof. (For the record, at the end of his life, the artist lived with a younger woman and two sailors.) One might ask whether this matters. And, moreover, what about the paintings themselves?

For Caillebotte was a highly original artist. This is more than evident in this major exhibition of some 65 paintings and almost half as many drawings – supplemented by male costumes and accessories, and family photographs. Caillebotte painted the domestic sphere, the traditional preserve of women and of women artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, although he was not the only male artist to do so. His images, in contrast to theirs, tend to feature brothers, male friends and family servants. These men read, pay calls, lounge or stare out of the window. One plays billiards, a group gathers for the fashionable card game of bezique. This is a leisurely world of the slightly bored – the affluent Caillebotte family divided their time between Paris and a country estate. (The artist had no need to sell his paintings, and the majority remained with his family, which is why his work began to be reassessed only in the 1970s.) With the exception of the aforementioned Jeune homme à sa fenêtre, which owes an intriguing debt to German Romanticism, these paintings are far from his finest.

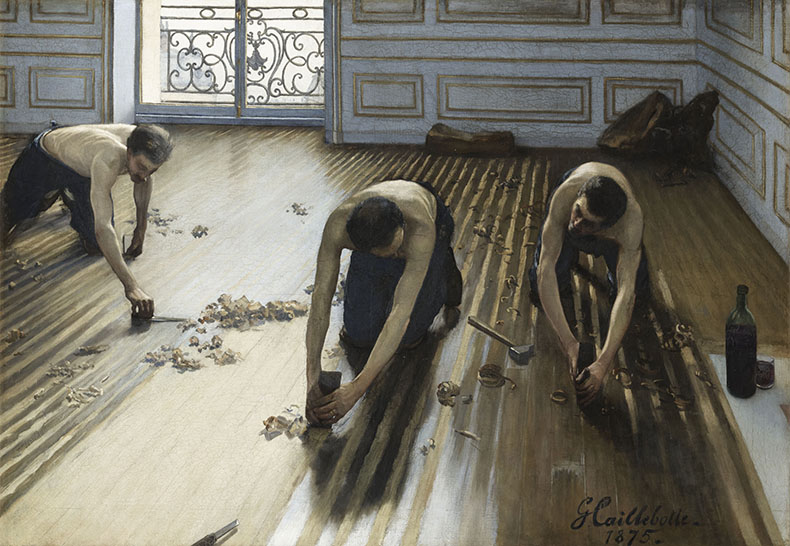

While Millet and Courbet had depicted the unidealised, back-breaking work of the rural poor, Caillebotte’s contemporaries found a new social realism in modern urban labour. Most chose female subjects – Degas memorably depicting the petites filles, the laundresses and milliners often obliged to supplement their meagre earnings with sex work. In his first major painting, Raboteurs de parquet (Floor-scrapers), unveiled at the Impressionist exhibition of 1876, Caillebotte instead looked to sinewy bare-chested workmen who, bent over and crawling along the floor on their hands and knees, intently scrape away the edges of buckled floorboards. The light suffusing the interior to articulate the stripes of the wetted and drying floor, and the curious curls of wood shavings, must have intrigued the painter’s eye, as did the patterns of the panelling and balcony grille.

Raboteurs de parquet (Floor scrapers) (1875), Gustave Caillebotte. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

It is not his technique or approach that arrests – both are close to those of conventional academic Salon painting – but the subject-matter, its strangely poetic mood and, above all, the radical composition and scale. This monumentality, usually accorded to history painting, plus a high horizon line, plunging perspective and expanding, empty foreground – also favoured by Degas – became hallmarks of Caillebotte’s greatest works. His focus on rhythmic repetitions of diagonal line and pattern become increasingly apparent in complex compositions such as Peintres en bâtiment (The House Painters) of 1877 and Le Pont de l’Europe, painted the previous year. The subject of the latter appears to be as much the lattice of giant metal girders as the figures which cross it – the new bridge was one of the Second Empire’s most celebrated feats of civil engineering. Here lay the heroics of the modern city. Caillebotte is believed to have painted himself as the figure at the crux of this x-shaped composition. It is suggested that he is more interested in the young workman gazing over the yards of the Gare Saint-Lazare than in his female companion – if, indeed, that is who she is.

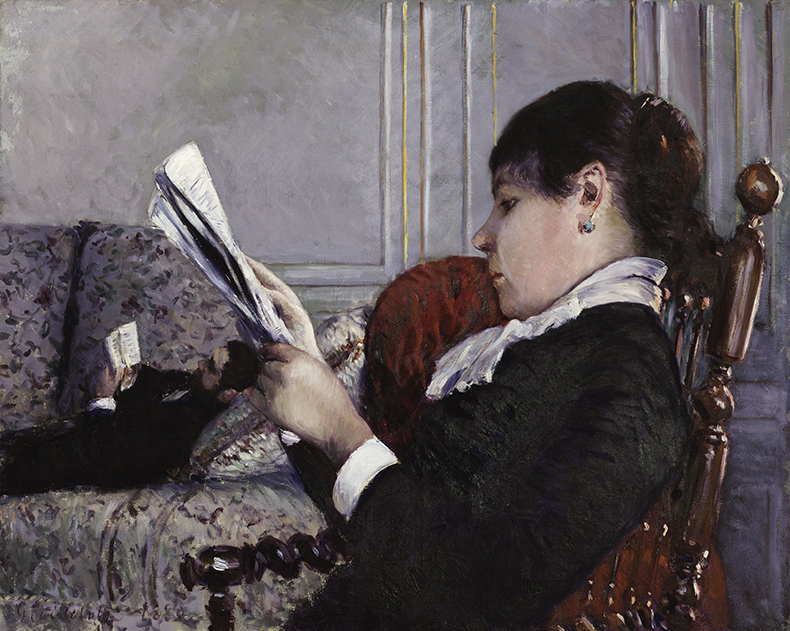

Inevitably, much is made of the two nudes at their toilette – both of them men, in contrast to the more familiar bathers of Degas. Yet between the two paintings hangs an even more explicit female nude, Nu au divan (Nude on a Couch) of c. 1880. Not included in this show is an early pastel of a female nude and Femme à sa toilette (Woman at a Dressing Table) of around 1873, an intimately observed domestic scene of a young woman dressing, which would have counterbalanced this emphasis on the masculine narrative. The artist used his female companion, Charlotte Berthier, as the model for Intérieur (Interior) of 1880, painted after his mother’s death when he and his brother Martial had moved to an apartment on the Boulevard Haussmann. Here she sits concentrating on her newspaper, while behind her a diminutive male figure sprawls on a sofa apparently reading a novel. This image of gender role-reversal offers a different facet to this exploration of modern masculinity. Did he wish, as is suggested, to present a male ideal that defied gender stereotypes?

Intérieur (Interior) (1876), Gustave Caillebotte. Private collection. Photo: © Caroline Coyner Photography

There is, however, no mistaking the virility of the myriad oarsmen heaving away at their oars in the river scenes that succeeded the artist’s ambitious series of streetscapes. None is more arresting than the Canotiers of 1877 which has us sitting in the boat along with the rowers, their concerted physical effort akin to that of the floor-scrapers. With these outdoor sporting scenes of regattas, boating and swimming – Caillebotte himself was a keen amateur yachtsman – the artist is credited with inventing a new genre.

No less innovative is the breathtaking audacity of the ‘bird’s-eye’ view from his balcony, Boulevard vu d’en haut, of 1880. This looks down through the branches of a tree to the street below, the curving, brightly leaved branches echoing the shape of the tree-grate at its base. The composition is found to owe nothing to either Japanese prints or contemporary photography. It is another, particularly original example of the painter’s fragmentary snapshots of modern reality.

Boulevard vu d’en haut (Boulevard seen from above) (1880), Gustave Caillebotte. Private collection. Photo: © Comité Caillebotte, Paris

Much of Caillebotte’s work remains ambiguous in its meaning, and thus open to interpretation. Even so, the notion that the artist would, for example, have considered himself ‘exploring his bourgeois identity’ is ludicrous. If the intention of the curators was to stimulate discussion, they have succeeded.

The advantage, however, of seeing these marvellous works of art at the Musée d’Orsay is that the exceptional collection of paintings that the artist acquired while supporting his fellow Impressionist friends and colleagues, and which were subsequently bequeathed to the state, is gathered together for a special display on the museum’s fifth floor.

‘Caillebotte: Painting men’ is at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, until 19 January 2025, then travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, from 25 February–25 May, and the Art Institute of Chicago from 29 June–5 October.