The exhibition ‘Harold Gilman: Beyond Camden Town’ at the Djanogly Gallery in Nottingham marks the centenary of Gilman’s death during the great influenza epidemic that swept through Europe in the wake of the First World War, killing more people than the war itself. The artist died on 12 February 1919, the day after his 43rd birthday. Amazingly it is nearly 40 years since the last exhibition devoted entirely to his work, though it is well-represented in public collections throughout the UK and remains familiar through shows and publications devoted to the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town groups, and his close association with Walter Sickert, Spencer Gore and Charles Ginner.

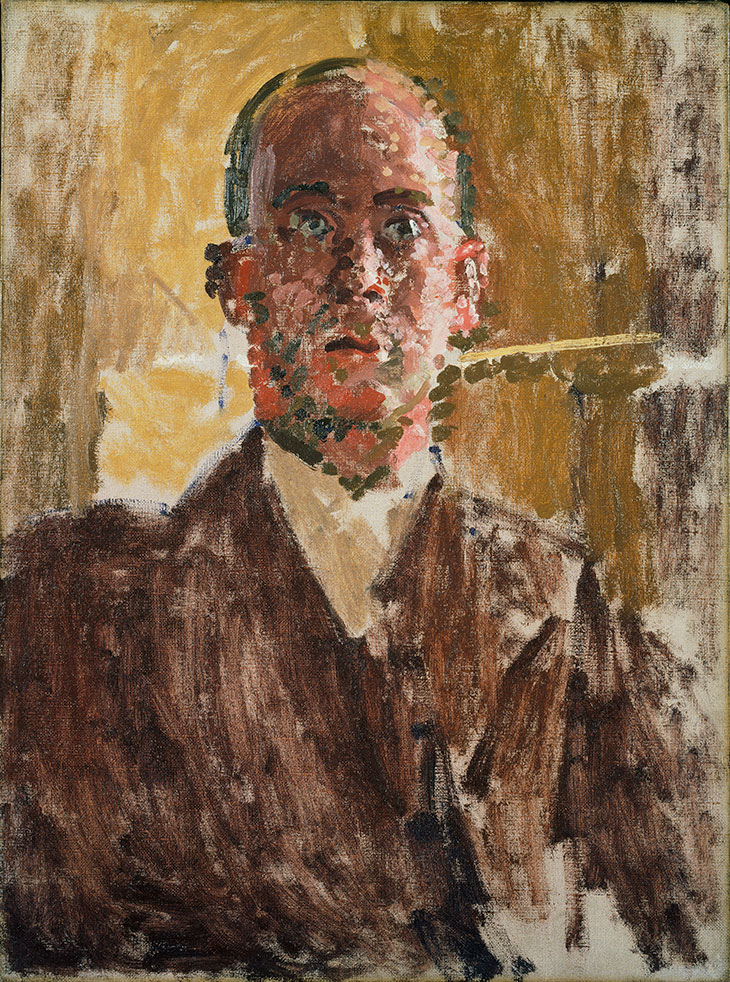

Harold Gilman (c. 1912), Walter Richard Sickert. Tate

Gilman’s background was firmly middle class and respectable: he was born at Rode in Somerset, the second of seven children of the Reverend John and Emily Gilman. Later, when his father became vicar of a parish on Romney Marsh, he was sent as a boarder to Tonbridge School, progressing briefly to Oxford and then as a tutor to an English family in Odessa. On his return to England he went to Hastings School of Art, followed by four years at the Slade. These biographical facts omit mention of the most traumatic event of his life, which also shaped his career. As a teenager he was tripped up racing down a school corridor, fell heavily on his hip and was bedridden for two years; the accident crippled him for life, leaving one of his legs shorter than the other. It was during his forced confinement that he began to draw.

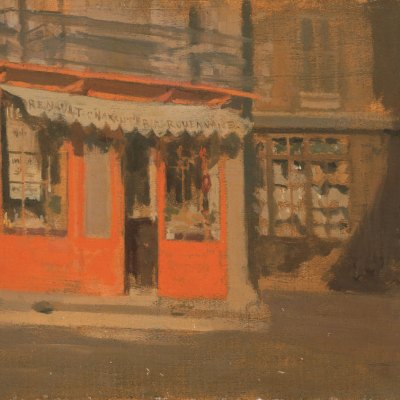

After leaving the Slade Gilman went to Spain, where he copied works by Velázquez and Goya, and met his first wife, an artist from Chicago named Grace Canedy. Together they visited Canada and the US, and back in England both husband and wife exhibited in the inaugural Allied Artists’ Association exhibition in 1908. Shortly afterwards Grace decamped, returning to America with their three children. This is roughly the point at which the current exhibition begins, with most of the works dating from the last decade of Gilman’s life. As Wendy Baron writes in her essay in the excellent, well-illustrated catalogue, up until 1910 his ‘vocabulary remained inoffensive, his handling that of a fluent Whistlerian tonal painter’.

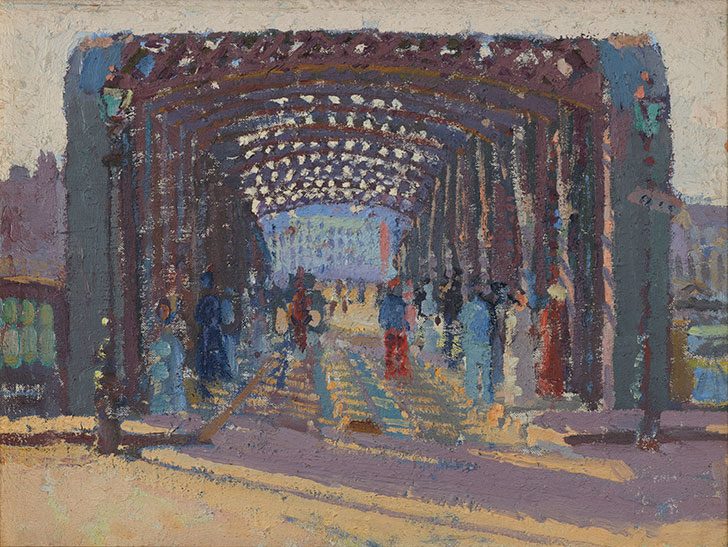

The Swing Bridge, Dieppe (1911), Harold Gilman. Photo: Douglas Atfield

It was not romantic strife, however, but a chance meeting with Sickert in February 1907 that catalysed Gilman’s artistic transformation. The exhibition opens with his scintillating painting of Gustave Eiffel’s Swing Bridge, Dieppe (1911), a thinly painted Impressionist work composed of dappled brushstrokes. It marks a turning point in the evolution of his technique from nostalgic fluidity to the opaque, highly wrought, almost jewel-encrusted surfaces one associates with his mature work. Elsewhere, as a founding member of the Camden Town Group he wholeheartedly adopted the Sickertian repertoire of what Baron summarises as ‘down-at-heel models in dingy bed-sitters, bric-à-brac on mantelshelves, run-down areas of north London, ill-favoured nudes on iron bedsteads’. Yet, while Sickert’s works from this period, such as the Camden Town Murder series, are invested with emotion and narrative, Gilman gives priority to the matière of paint rather than content. Through a ruthless analysis of his sitters’ features and carefully applied, thick dabs of paint in reds, blues and greens, he gradually built up the surfaces of his canvases. Although he shows some sympathy with his models, they are as much vehicles for technical experimentation as flesh-and-blood human beings; he can empathise equally strongly with a bowl of pears.

Twenty-six of the works in this exhibition are of single figures, almost invariably female, middle-aged, care-worn and weary. The most famous is the Tate’s portrait of Gilman’s landlady Mrs Mounter, with her gentle air of acceptance of life’s hardships; a generation later she could have been Tommy Handley’s model for Mrs Mopp in the wartime radio comedy It’s That Man Again, known for her catchphrase ‘It’s being so cheerful as keeps me going’. An outstanding exception among this array of models is the 1917–18 portrait of Gilman’s mother seated, relaxed in a wickerwork armchair, reading a book, her features defined by the subtlest of tonal modelling. Painted in the last years of his life, this portrait may have been a harbinger of potential change – he had recently married again, to another artist named Sylvia Hardy, and entered a new phase of domestic calm and stability. Sylvia and their small son John are depicted in Mother and Child (1918) – the painting, held in the Auckland Art Gallery in New Zealand, is reproduced in the catalogue and represented in the exhibition by one of Gilman’s stark, schematic preliminary drawings.

Study for Leeds Market (c. 1913), Harold Gilman

From his teenage years on, drawing was an important activity for the artist and he developed a quick shorthand technique, akin to that of Van Gogh’s. These remarkable ink drawings, of which there are a number in the exhibition, show his ability with a minimum of lines and dashes to grasp the essential essence of his subject – be it figure, landscape, the skyline of Dieppe, the harbour at Halifax, Nova Scotia, or a complex structure such as the canal bridge at Flekkefjord. The most extreme example here is his study for Leeds Market, shown in conjunction with the finished painting from c. 1913, in which the intricate web of girders supporting the roof of the vast hall is set down with breathtaking confidence. It is a beautiful drawing in its own right, as well as a document containing all the information required for the canvas that was to follow.

‘Harold Gilman: Beyond Camden Town’ at the Djanogly Gallery, Nottingham Lakeside Arts, University of Nottingham, until 10 February 2019.