As he prepares for an exhibition at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham – his largest

show in the UK to date – Haroon Mirza talks to Gabrielle Schwarz about ‘composing’ with light and sound, and his creative criticism of Louis Vuitton.

How did you become interested in sound, light and electricity?

I’ve always been interested in sound and music. I’ve DJed from a very young age and been into various types of music – not making music, as I never had the patience for that, but thinking about how it’s constructed, and the difference between visual space and acoustic space.

Then I started my Masters in design at Goldsmiths, and I remember we did a workshop with some architects, a hacking workshop. At this point I was becoming interested in creating autonomous systems – systems that operate autonomously with electricity and natural processes. During the workshop I realised I could generate sound from LED lighting. Slowly it emerged that I could use sound as a compositional material. And then I found other things like energy-saving light bulbs, radio waves and other materials and technologies that I could play around with and use as sonic elements.

In the past you’ve described your role as that of a composer. Could you expand on that analogy?

Being an artist is quite a broad thing, so for me it was about trying to define what it is I do. And ‘composition’ is a word that’s used in many disciplines, whether it’s architecture, design, painting, sculpture, music. We live in a time in which those artistic disciplines are breaking down – and rightfully so. The only reason they have existed for the last few hundred years is because of the art market industry and economy.

The Enlightenment has a lot to answer for in terms of how it imposed the need for categorisation. That’s why we have this thing called ‘art’, which is actually lots of things, but it’s also none of them. ‘Composer’ is a word that I am comfortable with because I compose things – objects and materials and images in space, and sound in time.

Taka Tak (2008), Haroon Mirza. Courtesy British Council Collection, Lisson Gallery and hrm199

The show at Ikon spans much of your career to date. Has it led you to think about how your work has evolved?

Yes, in a way all the works in the exhibition have been selected to show that evolution. Looking at them together has also really helped me to identify what you could call the ‘signature’ of my work.

There are a few things that have become apparent. One is the sound element – this process of generating sounds that are latent in everyday objects. Then there are all the electronics that control the work, also openly presented as part of the installation. Then there’s the visual logic, which could be described as assemblage – of sound, objects and materials arranged in various ways. There are coloured cables, and objects on turntables, and in later work there are solar panels arranged in geometric forms that provide electricity to power other elements.

The newest works in the exhibition [collectively titled Rules of Appropriation] are these solar works that refer to, or are inspired by, a series of window displays that the fashion brand Louis Vuitton did, which were themselves very close to the work that I’ve been making over the last several years. There was no communication with the brand about this, they just did it.

What’s your stance on appropriation?

It’s always been a part of my work, whether I’m thinking about cultural appropriation, or appropriating materials like video or objects, or other artworks sometimes. I’m not personally into copyright and the protection of ideas – I think ideas are in the realm of knowledge and should be shared. But in the fashion industry it’s all about brands and identity. Once in Venice, a long time ago, I saw a guy getting his arm broken by the police for selling counterfeit bags. At the same time brands think it’s fine to appropriate things themselves. I don’t think it’s fair and correct that they do that. It’s really worrying when something that you spend time and energy in developing for another purpose, for a more discursive reason, gets reduced to a gimmick and something that is used to sell objects, sell things.

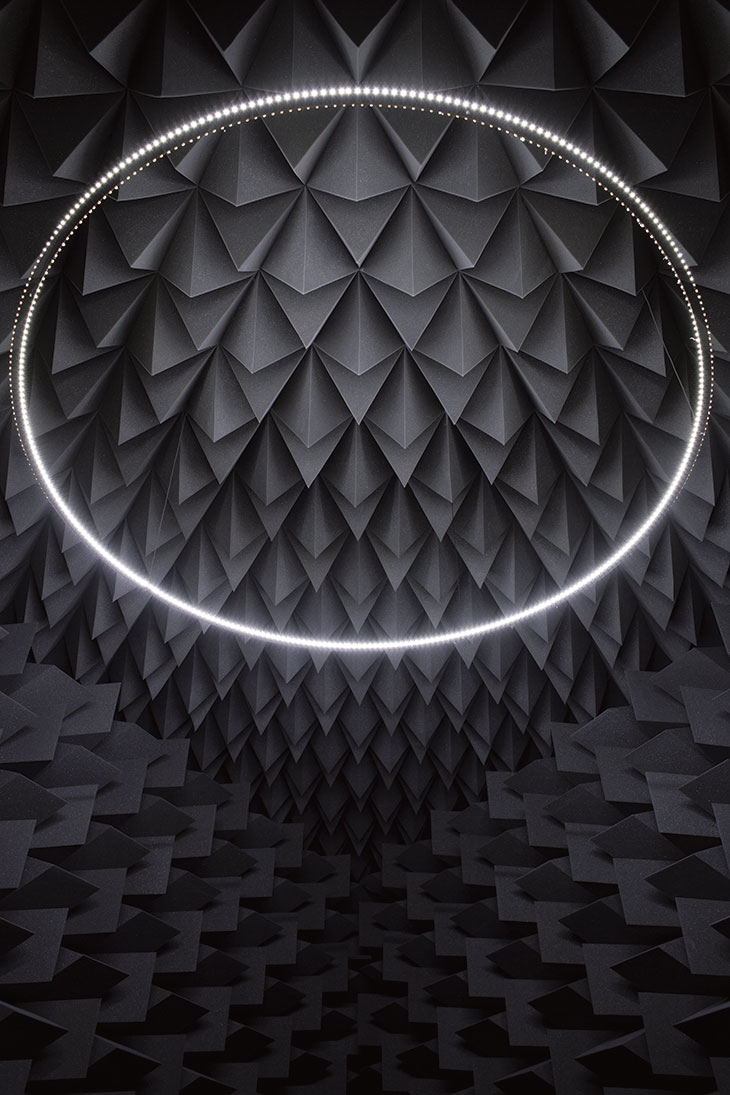

The National Apavilion of Then and Now (2011), Haroon Mirza. Installation view at the Venice Biennale, 2011. Courtesy hrm199 and Lisson Gallery

How important to you is it that the ideas behind your work are communicated to the viewer?

It’s not really important to me in the sense that that’s what they need to get; I think there are layers of content that you can dig into if you wish. Some of my works are more experiential than others, which demand that you interrogate them a little more – works such as Taka Tak [2008], which was named after a residency in Lahore in Pakistan and talks about the place of music in Islamic culture. And then there’s something like The National Apavilion of Then and Now [2011], which is a triangle-shaped anechoic chamber – a room that absorbs all the reverberation in the space. It’s also very dark so you lose a sense of where you are. There’s a halo of light above your head and it gets brighter and brighter, and you hear the sound of the electricity that’s driving it, and that gets louder and louder until it just cuts out. You’re thrown back into darkness, you’ve got these dots in your eyes – phosphenes on your retina – and you might sense a slight bit of tinnitus. It’s kind of pure experience: it’s a really minimal work, but so much happens in terms of your physiology and your psychological response.

Is minimalism an important reference point for you?

Yes, all the artists that are usually associated with minimalism, although they didn’t really call themselves minimalists – people like Fred Sandback, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin – have a great influence on and relevance in my work, although their work really stops at light. Then you’ve got people who were doing the same kind of thing with sound, composers such as Philip Glass and Stockhausen and Steve Reich. So I guess the anechoic chamber was combining sound and light in a minimalist gesture – although that’s just one way of defining it.

‘Haroon Mirza: Reality Is Somehow What We Expect It To Be’ is at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, from 30 November–24 February 2019.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.