The liberation of most of Mosul from the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) made global headlines in April. Largely lost in the coverage of the conflict was the recapture of another significant site at the end of the month: the Roman-period city of Hatra. On 26 April Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces announced they had recaptured the site from ISIS after fierce fighting.

Hatra rises out of the desert some 90 kilometers south of Mosul in the midst of a network of usually dry wadis. Its forlorn location belies its once fabulous wealth. Caught between the twin superpowers of the Roman and Parthian Empires, Hatra was well positioned to make a fortune by taxing trade caravans looking to take a shortcut across the desert.

Like Palmyra to the west and Petra to the south, Hatra became fabulously wealthy. The ancient city measured two kilometres across with a massive ornately decorated temple complex right in the middle of it. It was ringed by a massive fortified wall.

Hatra was a client state of Parthia for most of its history and its wealth made it a frequent target for the Romans. The emperor Trajan besieged it without success in AD 116. Septimius Severus laid siege to Hatra twice in AD 198.

The UNESCO-listed ancient city of Hatra, south of Mosul, on 27 April 2017. Iraqi forces recently retook the archeological site from ISIS militants. Photo: AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty Images

Each time, the city’s location worked against the attackers. While the defenders had plenty of water locked away inside the city walls, the desert in every direction offered none for the besieging army. Any party that broke away from the army to search for supplies was immediately attacked and slaughtered by Hatrene cavalrymen. As the Romans approached the city walls the defenders used catapults to lob jars filled with hornet nests at the attackers. Burning oil poured over the walls set both siege engines and the men manning them on fire. But the desert was the biggest killer: after three weeks Severus’ army had lost more men to heatstroke and disease than in combat. With mutiny brewing in the ranks, he broke off the siege and retreated to Palestine.

Hatra would eventually fall, not to the Romans but to the forces of the Sassanid king Shapur I in AD 240 as he sought to mop up the last remains of the Parthian empire which his father had destroyed. Shapur was a brutally efficient siege warrior. During a later siege of the Roman city of Dura-Europos in Syria in AD 256 his troops made the first known use of poison gas in warfare.

Shapur had both Hatra and Dura-Europos razed to the ground and neither was ever rebuilt. In AD 363 the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus described Hatra as ‘an old city lying in the midst of a desert and long since abandoned.’

The desert preserved the ruins of Hatra, which were excavated, conserved and restored by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1960s and 1970s. The city famously served as the film location for the opening scene of The Exorcist in 1973. Its very remoteness likely protected it from damage and looting in the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq invasion, but the city was captured by ISIS in 2014.

In March 2015 reports swirled through the media that much of the city had been destroyed, but when ISIS released a video of the destruction the next month it showed a few men with sledgehammers and machine guns defacing or shooting a few statues without destroying any of the buildings.

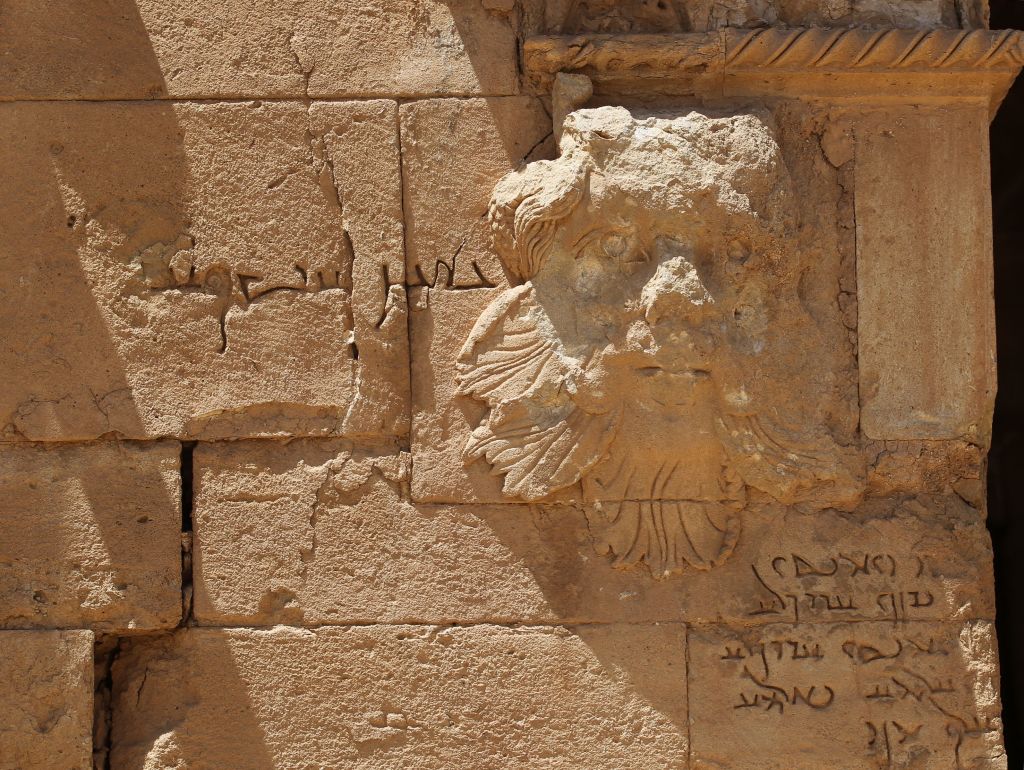

An Aramaic inscription next to this relief identifies it as a Gorgon. A video released by ISIS in 2015 features a militant attacking the piece with a sledgehammer. In this photo (taken 27 April, 2017) damage can be seen to the top of the head and nose. Photo: AHMAD AL-RUBAYE/AFP/Getty Images.

Now that Iraqi forces have recaptured the site the reason they spared the buildings has become apparent: ISIS was using the area of the Great Temple to train its troops in urban warfare. Climbing ropes and obstacles were set up among the stone walls. The surviving human sculptures had targets affixed to them and are covered in bullet holes showing that they were repeatedly shot as part of training for room-to-room fighting. Other parts of the site were used to store ammunition and explosives.

ISIS likely chose to place a training center inside the ruins of Hatra because they knew that coalition warplanes would not bomb a priceless historical site. However, paradoxically by doing so they also preserved the site, as a completely destroyed site could not provide the cover they desired. The damage so far appears to be light. Aside from numerous bullet and shrapnel scars in sculptures and walls the buildings all appear to be structurally sound and the site appears in much the same state as it was in the 2015 video.

Bullet holes can be patched and walls repaired. Hatra’s remoteness may never allow it to become a major tourist attraction, but it also aids its survival – something which is no doubt a comfort to many Iraqis.