Museums have been getting into the surveillance game lately, and we don’t mean CCTV and enhanced security measures to pre-empt protestors. We’re thinking, instead, of the institutions turning the tables on visitors looking at the work on the walls – by looking more closely at what those visitors are seeing. Last year, for instance, researchers tracked the eye movements of viewers of The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch at the Prado and found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that hell is a much more appealing prospect. And, just the other week, the Mauritshuis in The Hague revealed the results of eye-tracking equipment connected to a brain scanner, which found – again unsurprisingly? – that people tend to look Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in the eye, before their gaze wanders over the rest of the canvas.

Art Rate Monitor’s results are in for a painting by the Canadian artist Florence Carlyle. Photo: courtesy AGO

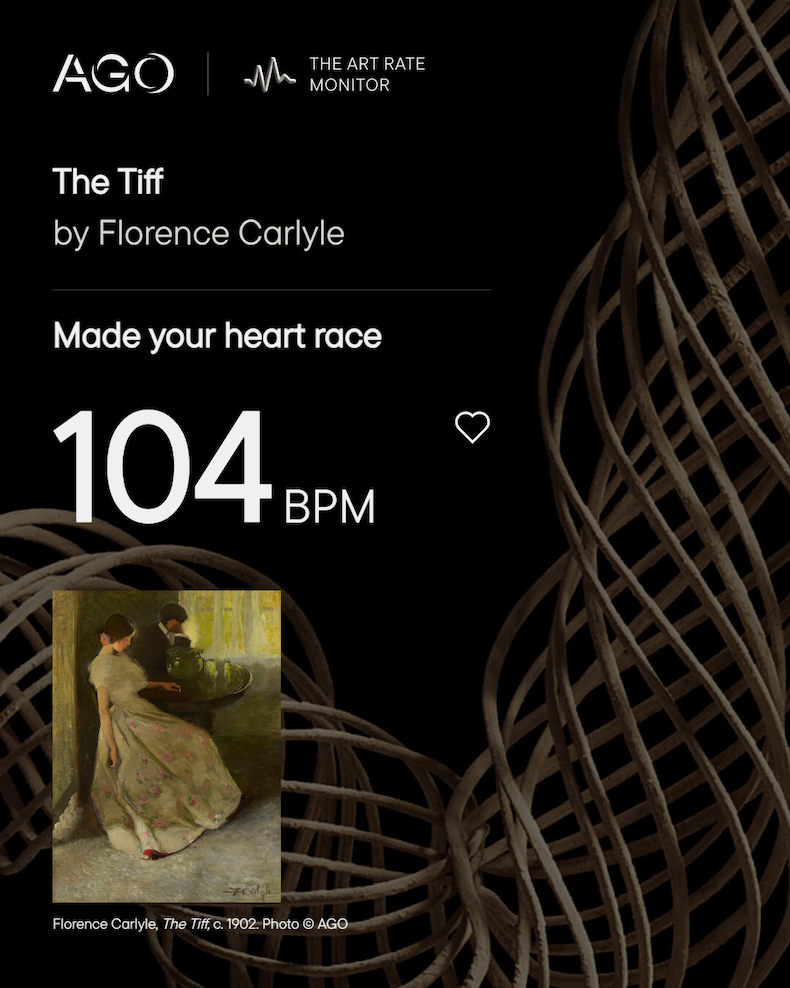

Now, the Art Gallery of Ontario has taken things further, in the interests of fun, with its Art Rate Monitor scheme. Since it launched in September, more than 3,000 visitors have moved round the Toronto Museum with a heartrate monitor and had the results summarised for them in an email at the end of their tours. This time the ‘findings’ are a little more unexpected. Rakewell wouldn’t quibble for a moment with the idea that Gerhard Richter is a great painter, but wouldn’t have predicted that his photo-realistic work Helga Matura (1966) would stop people in their tracks for so long – and slow the heart rates of the 20–30 age group more than that of any other group. And if viewers in the 30–40 age bracket are most stimulated by Otto Dix’s ghostly Portrait of Dr Heinrich Stadelmann (1922), is this the onset of midlife Weltschmerz?

The Heart of Mary (1759), Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz. Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

It’s true that some general practitioners have, from time to time, prescribed cultural activities to their patients, but we are, one hopes, some way off from doctors telling us to stand in front of a Rothko to relieve stress. But while we’re thinking about the cardiac side of art, perhaps we should go straight to the heart of the matter? In a new book called The Beating Heart (Head of Zeus), Robin Choudhury, a professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Oxford, charts depictions of the art from ancient ayurvedic texts to Renaissance anatomical diagrams to the Surrealists and beyond. Rakewell is particularly keen on the medieval German story of Frau Minne, who in an allegory of courtly love, has power over men’s hearts – and on the wonderfully literal depictions of the sacred and immaculate heart in mid 18th-century paintings from Mexico.

But a project much closer to Rakewell’s heart is Christian Boltanski’s Les archives du coeur (Heart Archive). In 2008, the artist began asking people to record their heartbeats in booths placed at his exhibitions, all over the world. The results were then added to a collection of audio files kept in a museum on the uninhabited island of Teshima in Japan. A recording of your roving correspondent’s heartbeat is in there somewhere (made at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2010). Perhaps it’s high time for a reunion – and to see what the Art Rate Monitor would make of the encounter?

Lead image used under Creative Commons (CC BY-NC 4.0)