When your name is in the dictionary as an adjective then you’ve reached a certain level of fame. Elon Musk may be one of the most famous people in the world, but his name isn’t an adjective and if it were, it probably wouldn’t be for anything good. Having a museum dedicated to your life’s work is also testament to a successful career and a good measure of fame. Since Elon Musk doesn’t have one (yet), this is just another area in which he is trumped by the English cartoonist William Heath Robinson (1872–1944). In 2016 the Heath Robinson Museum opened in Pinner, the suburb of north-west London where the artist lived during his most productive decade. Pinner is deep into what is known as ‘Metroland’ and full of what John Betjeman called ‘sepia views of leafy lanes’. If Elon Musk does ever has a museum dedicated to him it will be somewhere much showier, but Robinson’s life and work seem well suited to the pleasant park of which his museum now occupies a corner next to a duck pond.

The museum’s permanent collection tells the story of Robinson’s life and career, describing a hard-working illustrator who lived a reasonably modest and happy life mostly on the outskirts of London. After leaving the Royal Academy Schools in 1897, Robinson wanted to become a landscape artist, but the need to earn a solid income led to him pursue a career in illustration, a career his father and two older brothers were already engaged in. This led to him finding his niche in drawing the weird and wonderful contraptions for which he is best known. By 1912 the phrase ‘Heath-Robinson contraption’ had entered the dictionary.

‘Doubling Gloucester cheese by the Gruyère method in an old Gloucester cheeseworks when cheese is scarce’ (1940), W. Heath Robinson. Heath Robinson Museum, Pinner

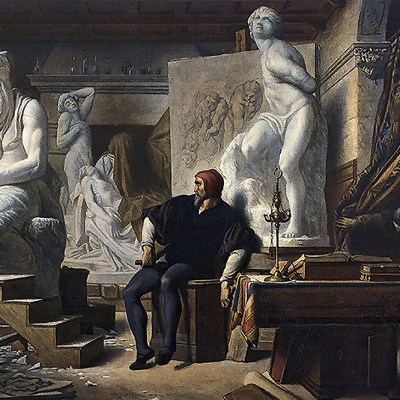

Throughout the museum are reminders that Robinson had to make a living; he married his long-time fiancé Josephine after a night of working ‘until the small hours’ and buying his suit on the way to the church. There are instances of Robinson being entirely dependent on the needs of publishers (has anything changed for illustrators?). A project illustrating the works of Shakespeare, for which Robinson used a formal style, was never published because of the lack of a publisher in the United States. These more highbrow illustrating jobs seem to be the ones in which he took most pride. A photograph at the end of the permanent displays shows Robinson at his desk with these more refined illustrations for magazine and book covers on the walls. However, it is the drawings of outlandish contraptions that he produced regularly for The Tatler and The Sketch, that seem to have paid the bills – and explain why people might take the trip out of central London along the Metropolitan Line to Pinner today.

Drawings of these machines are at the centre of a temporary exhibition, ‘The Humour of William Heath Robinson’, which presents illustrations from 1905 through to 1943 and marks the 15oth anniversary of the artist’s birth. Even though Robinson’s magazine career took him through both World Wars, harmlessness seems to be the theme that runs through his work. Even when he tackled the horrors of the day, his depiction of German soldiers gassing British troops in the trenches from 1915, for example, is a million miles from John Singer Sergeant’s Gassed (1919). Instead of mustard gas, the Germans are shown spraying laughing gas at the British trenches. Robinson later wrote of the First World War: ‘I believe that our sense of humour played a greater part than we were always aware of in saving us from despair during those days of trial.’

Perhaps it was the avoidance of reality that made his cartoons so popular. A cartoon, Picking the Pickelhaube which appeared in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News in 1915 was inspired by a letter from serving soldiers. Robinson took up their suggestion to have a British soldier playing a game, the aim of which was to grab the spiked ‘pickelhaube’ helmets from the heads of Germans in the opposing trenches. Robinson imagined a makeshift fishing rod made of rifles strapped together with a bar of soap on the end of the line, the pickelhaube spikes sticking into the soap as it is cast above the opposing trenches.

‘German breaches of the Hague Convention – Huns using siphons of laughing gas to overcome our troops before an attack in close formation’ (1915), W. Heath Robinson. The Heath Robinson Museum

Heath Robinson’s work was so well regarded throughout the First World War that the US Army paid for him to go out and join them in France in 1918 – his one and only journey outside the British Isles. Meeting the troops doesn’t seem to have turned him into a realist, though, not that I imagine that’s why he was hired. A drawing of American troops published in The Sketch in 1919, depicts them ‘Taking a peak in the Vosges district’. It’s no battle scene, though, as the Americans are literally picking up the peak on which the Germans are encamped and using a combination of tractor, aircraft and a horse to pull it away, while a man on a bicycle follows poking the hill onwards.

Although the cartoonist may have taken more pride in his illustrations of scenes from Shakespeare, ‘The Humour of Heath Robinson’ shows why he was and is still so loved. He may have not have made a fortune or led a life of adventure, but from the suburbs he managed to make the fantastical creations that people have enjoyed for more than a hundred years.

‘The Humour of William Heath Robinson’ is at the Heath Robinson Museum, Pinner, until 4 September.