Art history is now a more rigorous discipline than was the case a century ago. As a result, it is less likely to produce figures like Tancred Borenius (1885–1948), the Finnish-born writer who was a regular contributor to this publication during its earliest years, and who will be remembered in London later this month when a plaque is unveiled at his former residence at 28 Kensington Gate. This will be followed by a seminar on his life and achievements at a venue in central London.

Borenius’s elegantly composed texts betray no hint that English was not his first language, although seemingly otherwise was the case when he spoke. As Durning-Lawrence Professor of the History of Art at University College London for a quarter of a century from 1922 onwards, his heavy accent left students struggling to understand what was being said; at least one of them attended because, as an insomniac, he found listening to Borenius more successful in achieving sleep than any medication.

This anecdote is recounted in a profile written by Denys Sutton and published by Apollo in April 1978, three decades after Borenius’ death. The two men had known each other, and Sutton’s account is affectionate. He recalled taking refuge one night during the Second World War in a London air raid shelter and there encountering Borenius, ‘spick and span, reading either Taine or Guizot, or was it Ollivier?’

That list of names gives an indication of the breadth of Borenius’s interests, wider than was or is common among art historians, and a reflection of his international background. Finland being still part of the Russian Empire when he was young, Borenius often travelled with his family to St Petersburg where he spent much time at the Hermitage. After studying art history at the University of Helsinki, he moved first to Berlin and then to Rome; while in Italy he completed a doctoral thesis which formed the basis of his first book, published in 1909, The Painters of Vicenza, 1480–1550. By this time he had settled in London, where he came to know Roger Fry and through him other key figures in the English art world. The same connection led Borenius to begin contributing to the Burlington Magazine, where he would eventually act as editor from 1940–44.

His association with that magazine by no means excluded engagement with others, not least Apollo which, according to Sutton, he played a part in founding in 1925. Unfortunately no records are known that detail the precise nature of Borenius’s involvement (early issues do not even carry the name of the magazine’s editor or staff), although Sutton proposes that he was ‘probably responsible’ for the generous amount of space devoted to music in the first years, with contributions every month from the likes of composer Constant Lambert (‘who at one stage supplemented his income by playing Wagner on the piano for the Boreniuses at home’) and Ernest Newman. Friends of Borenius such as Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell, and Desmond MacCarthy were also pressed into writing for Apollo, their articles appearing alongside more established art historians.

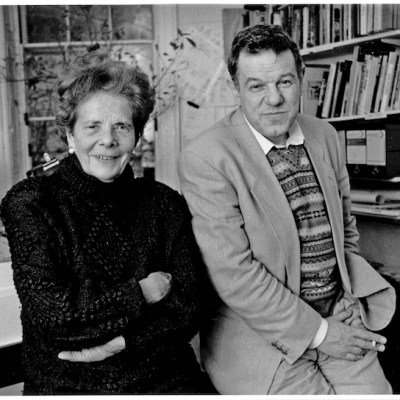

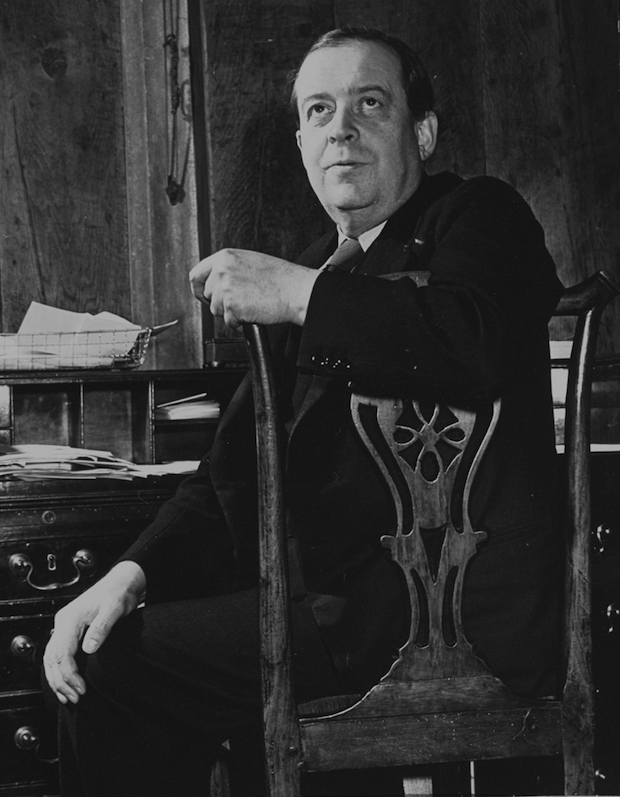

The Finnish art historian Tancred Borenius (1885–1948), photographed in his office in 1940. Photo: William Vandivert/Getty Images

Borenius’s own contributions began in the second issue (February 1925) with a feature on ‘Early Italian Pictures in the Collection of Lord Carmichael’, a former colonial administrator. There followed similar pieces on aspects of the collections of Viscount Lee of Fareham and Viscount Lascelles. In both cases, while Borenius focused primarily on Italian pictures, his primary area of expertise, he also examined other schools, an indication of the extent of his interests. This became more apparent in later work for Apollo when he wrote on such subjects as English illumination (June 1928) and Queen Mary’s collections of Chinese jade and enamels (November 1933 and July 1934 respectively). Access to the latter came through the queen’s daughter, Princess Mary, who in 1922 had married the aforementioned Viscount Lascelles, later sixth earl of Harewood. Between 1929 and 1939 Borenius and his family spent a month every summer at Harewood House, Yorkshire, where they would be joined by the queen. Borenius paid visits with her to other properties and antique dealers in the area.

Borenius’s 1925 article on the Lascelles collection of Old Master drawings, erudite and informative as was ever the case, fails to touch on one crucial point: his own role in its assembling. For much of his career, Borenius, who had expensive tastes as well as a wife and three children to support, maintained links with the commercial art world, advising Sotheby’s on Old Master paintings, drawings and prints, as well as performing similar services for Agnews at one period. He was therefore admirably placed to offer the benefit of his wisdom and connections to Viscount Lascelles, who in 1916 had inherited the estate of a great uncle, the very rich and very parsimonious second Marquess of Clanricarde. A considerable portion of this inheritance was spent on developing the art collection at Harewood, with the assistance of Borenius. However, as already noted, the ‘full disclosure’ that would now be regarded as necessary is absent from the text he wrote for Apollo: the majority of readers would likely have been unaware of his part in amassing the pictures under discussion.

Autre temps, autre moeurs. What might now be judged a conflict of interests was then not unusual. After all, both Sir Hugh Lane and Robert Langton Douglas continued to operate as art dealers while serving as director of the National Gallery of Ireland. Nevertheless, in James Stourton’s recently published biography of Kenneth Clark, it is made clear that when in 1934 the post of Surveyor of the King’s Pictures became vacant, Borenius, despite his friendship with the queen, was not appointed because he was felt to be ‘tainted by a too-close involvement with the art trade’.

Given the many subjects on which he wrote and spoke, Borenius also ran the risk of making mistakes in his attribution. Such appears to have been the case with a picture he discussed in the February 1926 issue of Apollo. Called The Love Letter and then owned by Detroit banker Julius Haass, the work was attributed by Borenius to Gabriel Metsu. Tellingly no provenance is provided, Borenius preferring to emphasise ‘the felicitous arrangement of the composition’ and the ‘exquisite harmony of colour and modulation of tone’ as providing irrefutable evidence of Metsu’s hand. The attribution has not stood the test of time, and today the painting, its present whereabouts unknown, is absent from the artist’s catalogue raisonné.

Mistakes of this sort were almost inevitable. Borenius’s output was prodigious, since he not only wrote for several art publications but also produced a succession of books and catalogues of private collections. In addition there was his lecturing, and for many years in the 1930s he oversaw the excavation of the medieval Clarendon Palace near Salisbury in Wiltshire. Contemporary accounts make it clear his extra-curricular hours were equally busy: the artist Adrian Daintrey, who as a student recalled Borenius’s ‘inaudible lectures in his own brand of foreigner’s English’ later encountered him in the guise of ‘the most gallant social butterfly possible’. Sutton called him ‘both cosmopolitan and erudite’ and one was as likely to encounter him at one of aesthete Stephen Tennant’s weekend house parties as at the opera in Covent Garden.

Multiple demands on his time meant that having been a diligent contributor to Apollo at the start (11 features in 1925, seven each in the two following years), his presence in the magazine gradually slackened. By the 1930s he only occasionally provided material, the last contribution being an article on ‘Masterpieces of English Illumination’ in May 1936. While the full story of Borenius’s involvement with this publication during its first decade may never be known, the diversity of the subjects on which he wrote and the assurance of his authorial tone – even if occasionally misplaced – helped to set a standard which has been maintained ever since.

For more information on the Borenius events in London on 23 March, contact Paulus Thomson.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here