From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘Now I feel we are in the real Provence,’ exclaims Henning Hoesch as we drive north-east from Marseille and catch a first glimpse of the red earth that is as distinctive to this region as the majestic Mont Sainte-Victoire that presides over it. It is a soil, and a landscape, that the German-born Hoesch has come to know intimately since he and his Swiss-French wife Julia acquired the Domaine Richeaume in 1972. There, they planted a vineyard and pioneered the production of organic wine in France; but another, far less likely, fruit also emerged from the fertile ground of the domaine: a collection of Italian – and Italianate – Old Master drawings. Oddly enough, these two projects are not unrelated.

Hoesch had never imagined he would become a vigneron – or, for that matter, a collector of drawings. He came from a family of prominent industrialists in the Ruhr, but elected for the life of the mind, studying – as one could at the time – at the universities of Cologne, Basel, Göttingen, Aix-en-Provence and Berlin before taking up a postgraduate fellowship at Yale. It was at Aix, in that year of academic revolution 1968, that he met Julia, and to Aix that they returned from the United States two years later. Hoesch ultimately found the manuscripts of medieval canon law frustratingly narrow and, at the age of 32, relished the prospect of a new challenge. The tragically early death of his parents put wind in his sails, and the couple’s fate was sealed when they saw a newspaper advertisement for Richeaume, its picturesque shuttered farmhouse nestling under the most famous mountain in the history of art. Although in parlous condition, it had been a working farm, producing garlic, lettuces, melons and corn. The only crop Hoesch could imagine devoting his life to cultivating was the noble vine, and thus the adventure began – after further studies in Dijon and Beaune.

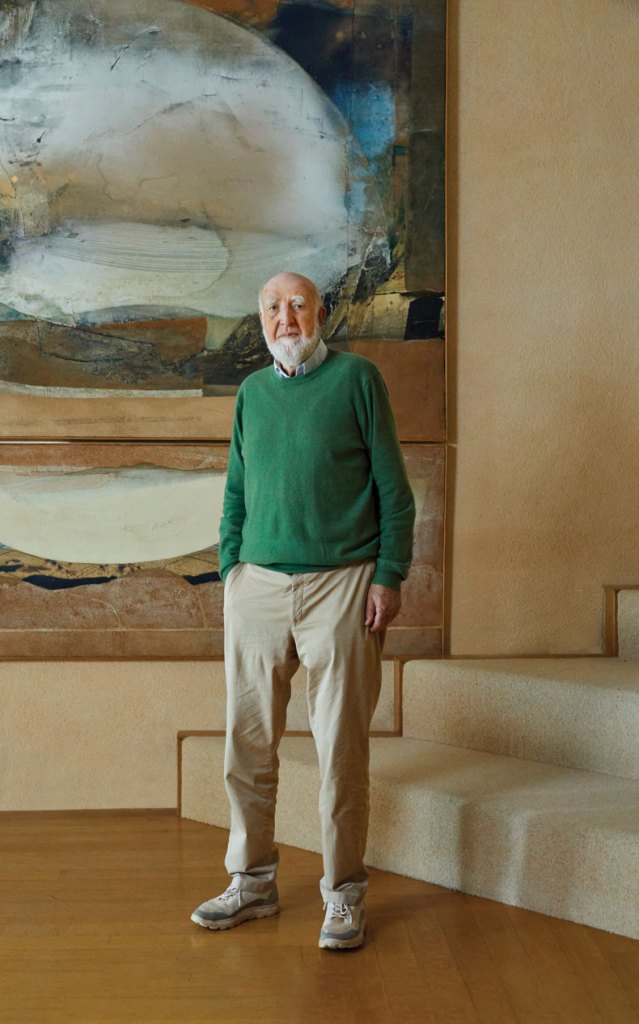

Henning Hoesch photographed in the Music Room of the Domaine Richeaume in Provence in October 2023. Photo: Magali Paulin

Walking with him around Richeaume, I soon realise how profoundly this magical place continues to move Hoesch, even after passing the estate over to his son, Sylvain, and returning to Germany for most of the year. Now in his 80s, he strides through the vineyards and terraces pointing out their features, natural and man-made, and nimbly negotiates vertiginous iron-red slopes to reveal the mysterious canyons formed by water rushing down from the plateau above. One of the reasons for choosing the organic and sustainable route over modern industrial farming, he says, was to preserve this very landscape.

Apart from the vines and olive groves, he and Julia have planted hundreds of ornamental trees, not least cypress, which are now of majestic scale, as well as fig, quince, persimmon and pomegranate among aromatic lavender, roses, rosemary and thyme. On clearing the overgrown fields around the farmhouse, they uncovered the remains of a sprawling ancient Roman settlement – walls, cisterns, fishponds, conduits and, over a small bridge, a cemetery. The site was subsequently excavated by archaeologists from Aix and York and is now left peacefully basking in the Provençal sunshine. Most auspicious was the discovery of a head of Bacchus, god of wine and festivity.

Hoesch’s alterations of the buildings and gardens include a grotto and cascade added to the terrace garden, inspired by the 16th-century Villa Lante in Viterbo – a similarly sloping garden, it too is animated by the constant splash of spring water and culminates in calm reflective pools. He recognised not only the quality of the vernacular stone masonry of the region but also its importance to the landscape. He and Julia have made traditional rustic walls built from differently sized stones – new and old – a defining feature of their work at Richeaume. The transformation of the neglected farmhouse and domaine could so easily have been a project of straightforward conservation and restoration, and pretence, with the plant of the winery hidden behind old facades and roofs. Instead, for this progressive working estate they chose to combine traditional techniques and modern materials to restore and rebuild imaginatively and unapologetically. As Lampedusa has one of his characters say in The Leopard (1958): ‘Everything must change for everything to remain the same.’

View of the outdoor theatre and concert space, designed by Odette Ducarre. The sculpture in the foreground is by Susanne Knorr. Photo: Magali Paulin

The first things to go were the hideous modern pigsties. In their place came solar-powered concrete cellars designed by architects Carlo Scarpa and Jean Tchepitchian, built immediately behind the house. Their temperature is regulated by the spring-fed and seemingly ornamental pool of water above them, which is ingeniously incorporated into an outdoor theatre and concert space. The presiding genius here, in the house and throughout the estate is the French modernist architect and designer Odette Ducarre, who had previously built a remarkable brutalist concrete home for the composer and conductor Pierre Boulez at St Michel-l’Observatoire, 40 miles to the north. Her starkly geometric minimalist interventions for Richeaume are unexpected and often witty. These range from oak furniture, doors and staircases to great stone curtain walls, concrete walkways through and across water, and the entire terrace garden, designed to regenerate the devastated landscape after the great forest fires that afflicted much of the south of France in 1989.

Music is part of Hoesch’s German cultural heritage – he himself plays the cello. He grew up on a beautiful estate belonging to his grandmother’s sister. After the war, the large farmhouse there was used to stage concerts for refugees. ‘I heard my first string quartet when I was six!’ he says. He and Julia have welcomed many distinguished ensembles to their indoor music room, and Sylvain has continued the tradition with a concert in support of Ukraine. Hoesch did not, however, inherit his parents’ enthusiasm for contemporary art.

The Music Room, with a staircase designed by Luis Barragán. Photo: Magali Paulin

Collecting entered his life in middle age, when the vineyard was established and its wines were already winning awards. It began in London when an old friend, the modernist photographer Elsbeth Juda, took Hoesch to Sotheby’s and they viewed a sale of Old Master drawings in 1986. ‘I had no idea I could afford these kinds of drawings,’ he explains. ‘As a young man, I had been very interested in drawings, but I only knew the big names. I was immediately attracted to a sheet of studies by Guercino. I had never heard of Guercino!’ He bought the drawing anyway.

This was one of the 17th-century Bolognese artist’s bold and calligraphic pen and brown ink drawings, a sheet of paper on which the draughtsman worked to give expression to the grief of a group of female mourners, and also to find the correct position for a particular leg. These kinds of first thoughts represent the very genesis of a work of art: you can almost see the artist’s thinking as he flourishes his pen across the page. The acquisition launched a collection that was to grow to number more than 100 works, dating from around 1500 to 1800 when, he says, ‘spiritually, the art of drawing changes.’ It was only much later, he says, that he began to understand why he collected and why certain drawings spoke to him. His focus on Italy was there from the start, though, guided by a long love of the country, which sprang from an early interest in Michelangelo and Leonardo and later travels relating to research on the relationship between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy. ‘This world of drawings was completely new to me. It was a second study, but also the second part of my life.’ Another challenge.

Studies of a Seated Female Figure (1600–20), Guido Reni

At first, Hoesch was intrigued by the question of attribution – that is, how a drawing may be identified by relating it to a ‘school’ of art (there seems hardly a city in Italy that did not have its own distinctive style) or by associating it with a known finished work of art. Most elusive of all is the kind of connoisseurship that enables someone to recognise the individual ‘handwriting’ of an artist. This kind of close, forensic study was both familiar and appealing to a man who had spent many years poring over medieval manuscripts, and was used to drawing from different sources of information for comparison and context. ‘You really have to be a detective,’ he says.

‘It is important to interpret the details of what you see,’ he continues, warming to his theme, ‘but the real reason for collecting drawings has nothing to do with making attributions.’ The reason lies in the drawings themselves and how they move us, speak to the soul. ‘For me, a drawing must be vivid. It must express a vitality and a timelessness,’ he says. ‘In a way it is a paradox, seeing perfection in something that is unfinished.’ He would far rather have a drawing than any finished painting: his collection is full of examples of drawings where the fluency and immediacy of the artist’s initial conception is lost during the laborious process of translating one into the other. What he is seeking is a quality ‘which transforms the provisional into the timeless’.

He cites no less an authority than Giorgio Vasari, the first historian of Renaissance art. Opening his copy of Vasari’s famous Lives, Hoesch reads passages describing history as ‘truly the mirror of human life’ and deeming ‘the pleasure that comes from seeing past events as present’ as ‘the true end of that art’. The subjects of Hoesch’s most valued drawings are certainly very present, their expressions and mannerisms no less recognisable to us today. The three men drawn around a table deep in thought and discussion might be spotted in any bar – the artist Salvator Rosa very possibly drew them in such a place, using what he saw for a representation of Joseph Interpreting Pharaoh’s Dream. A particularly bravura example is an ink drawing of A River God on the Bank by Jacques de Gheyn II, dated 1610. The river god is ruminating among reeds at the edge of a river. Hoesch says, ‘He is a perplexed old man who does not understand the world any more, and is so inward-looking that he fails to notice the two ducks flying past.’ By Vasari himself he has a reclining figure of Saint Mark, who is so engrossed in his book that he is oblivious to the fact that the lion beside him, his symbol as one of the four Evangelists, is biting his thigh: ‘It is such a comic drawing. I laughed when I first saw it, and still do.’

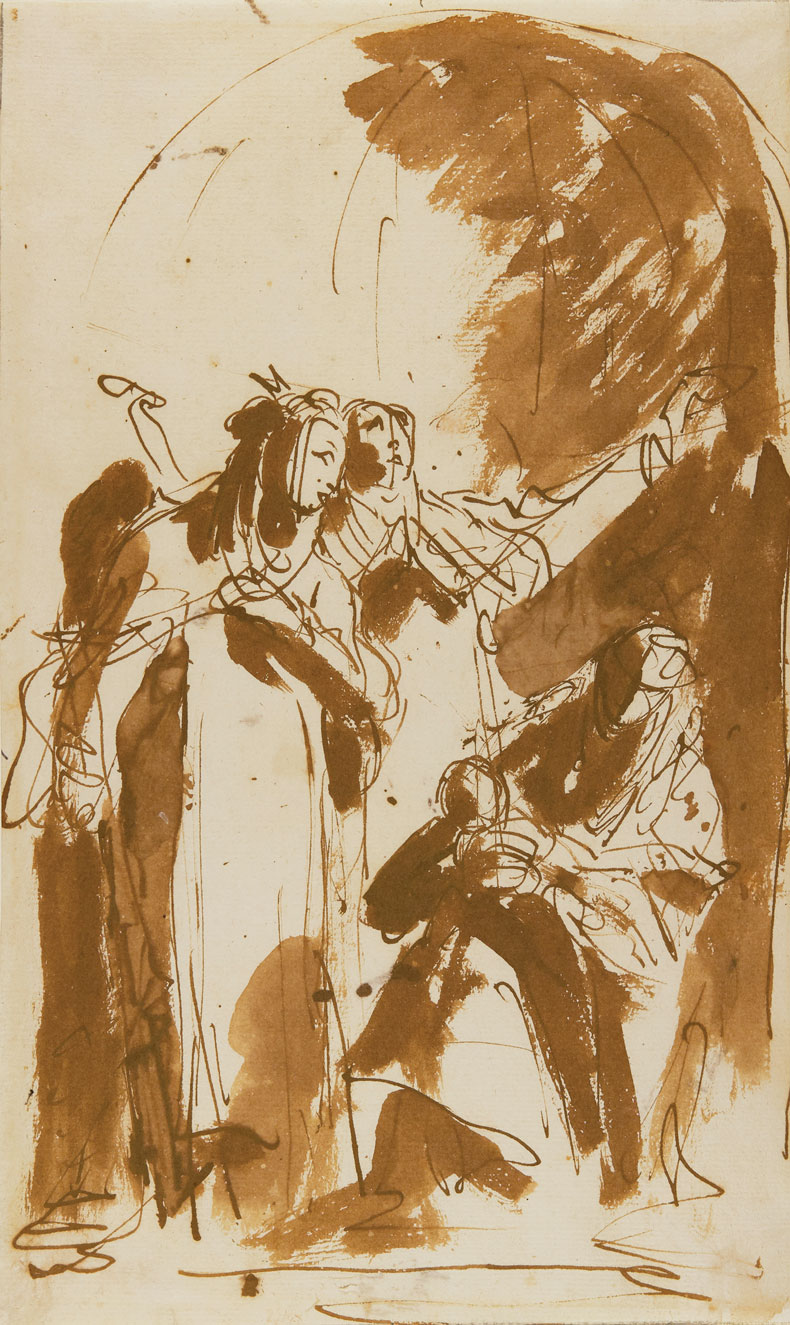

At the same time, Hoesch has continued to pursue drawings in which the artist rapidly lays down his thoughts with great economy, although there is always a sense of some kind of resolution. Guido Reni’s studies of a seated female figure show him searching for the most eloquent pose and expression. Telling line is combined with almost abstract wash in Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s sketch for his 1746 altarpiece of The Virgin Appearing to Saints Catherine of Siena, Rosa of Lima and Agnes of Montepulciano with the Christ Child. Few artists convey so much by so little as Claude in a sweeping panorama of the Roman Campagna with the so-called Villa of Maecenas in Tivoli, dated 1647. Landscape drawings, the collector says, appeal to him more and more.

The Virgin Appearing to Saints Catherine of Siena, Rosa of Lima and Agnes of Montelpulciano with the Christ

Child (1746), Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

These are all drawings in pen and ink, but while the collector is fascinated by an artist’s choice of medium and how he uses it, he has no particular favourite. The 17th-century Florentine artist Cecco Bravo, for instance, selected red chalk for his extraordinary drawing, perhaps for a ceiling fresco, of Phaeton Carried away by the Chariot of the Sun. It is an example of Hoesch’s penchant for finished drawings although, he insists, it remains a ‘real’ drawing in its freedom of handling, energy and movement. The four horses plunging headlong across the sky strain every sinew.

That first choice of Guercino demonstrated an instinctive taste for baroque at a time when what is often termed Mannerist art was much more the taste of the day. Hoesch is, after all, one of life’s independents – he chose to introduce grape varieties traditionally grown in Bordeaux and the Rhône, principally Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon, not to follow appellation guidelines, or follow his Provençal neighbours by focusing on rosé.

The Carracci family in Bologna – brothers Annibale and Agostino and their cousin Ludovico – challenged Mannerist excesses and initiated a return to a more naturalistic classicism, encouraging their students to draw from life. The relationship between these artists has long intrigued Hoesch and he continues to add to this group, most recently by a beautiful black chalk nude made by Agostino of a Mary Magdalene. He has also made discoveries among their oeuvres but perhaps no discovery is more thrilling than his identification of one of only two known drawings by El Greco, a study after Michelangelo’s figure of Day. ‘Beauty is a word we have not yet used,’ Hoesch announces, ‘and yet it is the most important.’ Another I suggest, is pleasure; both seem to be denied in the narrative around so much contemporary art. It was to reassert the importance of beauty and pleasure that Hoesch first published a two-volume catalogue of his Old Master drawings titled Galleria portatile (Michael Imhof Verlag) and then exhibited its highlights in the Museum of Prints, Drawings and Photographs in Dresden’s Residenzschloss in 2022. Book and exhibition were intended in part as a provocation, a polemic.

The Penitent Magdalene (1591–95), Agostino Carracci

He flourishes an image of Parmigianino’s study relating to his frescoes of the Wise and Foolish Virgins decorating the Church of Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma. ‘This has a perfection. It is an ideal of feminine beauty,’ he enthuses. It is clear to him that it gave Parmigianino pleasure to make his preparatory drawing beautiful as well as useful. In the catalogues, Hoesch hoped to transmit pleasure by encouraging others to take time to immerse themselves in the world of drawings, and in the mind and creative process of the artist – hence the exceptionally generous amount of comparative material. Hardly surprisingly, the cover of the first volume is Andrea Boscoli’s Triumph of Bacchus of around 1582.

After the wildfires of 1989, the drawings were taken to Germany for safekeeping. A reminder of the collection remains in a sleek oak table designed by Ducarre for viewing drawings – a streamlined curve combined with sharp angles, which she likened to a kneeling camel awaiting its burden – in one of the libraries. This is a house of libraries, each one devoted to a different phase of Hoesch’s life and interest. Richeaume is a place to read, work, play and listen to music and, of course, enjoy wine. Hoesch has preserved the spirit of the place by looking to the future, and sought the essential present in the art of the past.

From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.