From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When we look at stained-glass windows, in churches and homes, are we merely looking through them? In scholarly and popular terms, only the glass in the great gothic cathedrals is fully appreciated. Most of the time, subsumed as they are within the Gesamtkunstwerk, the windows can recede into the background. This makes George B. Bryant’s book about the English painter and designer Henry Holiday (1839–1927) all the more welcome. It makes a compelling case for looking at the windows he designed for Protestant churches in New York and beyond – and paying closer attention to late 19th-century stained glass in general.

Holiday, who trained as a painter at the Royal Academy School, is probably best remembered for Dante and Beatrice (1883), which now hangs in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. His education made him an ideal candidate to reassess and revive stained glass as a medium and he entered the field at an especially fortuitous time. Many ancient civilisations could make stained glass, medieval artisans had developed techniques to enhance the expressiveness of the medium, but the industrial revolution transformed the process. Business was booming in the mid 19th century, thanks to the popularity of decorated church interiors inspired by the Gothic Revival, but commentators were critical of the mechanical design and manufacture of most windows. While Augustus Pugin advocated a return to gothic examples, he combined stained glass (where pigment is added to the glass and fired at high temperatures) with glass-painting (where colour is added after firing) in his pioneering work with John Hardman & Company of Birmingham. Holiday followed his example by establishing a long and productive relationship with James Powell & Sons before striking out on his own.

Holiday, who trained as a painter at the Royal Academy School, is probably best remembered for Dante and Beatrice (1883), which now hangs in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool. His education made him an ideal candidate to reassess and revive stained glass as a medium and he entered the field at an especially fortuitous time. Many ancient civilisations could make stained glass, medieval artisans had developed techniques to enhance the expressiveness of the medium, but the industrial revolution transformed the process. Business was booming in the mid 19th century, thanks to the popularity of decorated church interiors inspired by the Gothic Revival, but commentators were critical of the mechanical design and manufacture of most windows. While Augustus Pugin advocated a return to gothic examples, he combined stained glass (where pigment is added to the glass and fired at high temperatures) with glass-painting (where colour is added after firing) in his pioneering work with John Hardman & Company of Birmingham. Holiday followed his example by establishing a long and productive relationship with James Powell & Sons before striking out on his own.

The first section of the book covers Holiday’s life and career up to the early 1880s, when the artist established himself as a painter, designer and illustrator. In 1861, he took up a position with Powell’s Glass Works after his friend Edward Burne-Jones resigned to work exclusively with Morris & Co. Bryant’s discussion of Holiday’s windows for the chapel at Worcester College, Oxford, among others, moves his subject out from the shadow of Burne-Jones, whose high-profile commissions and affiliation with William Morris made him synonymous with ‘Arts and Crafts stained glass’.

In the chapters on Holiday’s later work in the United States, the artists John La Farge and Louis Comfort Tiffany provide points of comparison and contrast, as their windows can often be found in the same churches. Holiday’s works are notable for how his painterly sense enhances the design; he suggests depth through the relationship with the landscape and architectural details and his rich colour palette makes for luminous viewing. Holiday viewed the innovations of La Farge in particular, who used opalescent glass and often twisted or flattened the glass while it was still soft, as the substitution of ‘accident for design’. This quality, as he noted in his book Stained Glass as Art (1896), rendered it ‘inadequate for monumental decorative art’. It was the monumental Holiday strove to create and in commissions for the Muhlenberg Chapel at St Luke’s Hospital in New York, he achieved it.

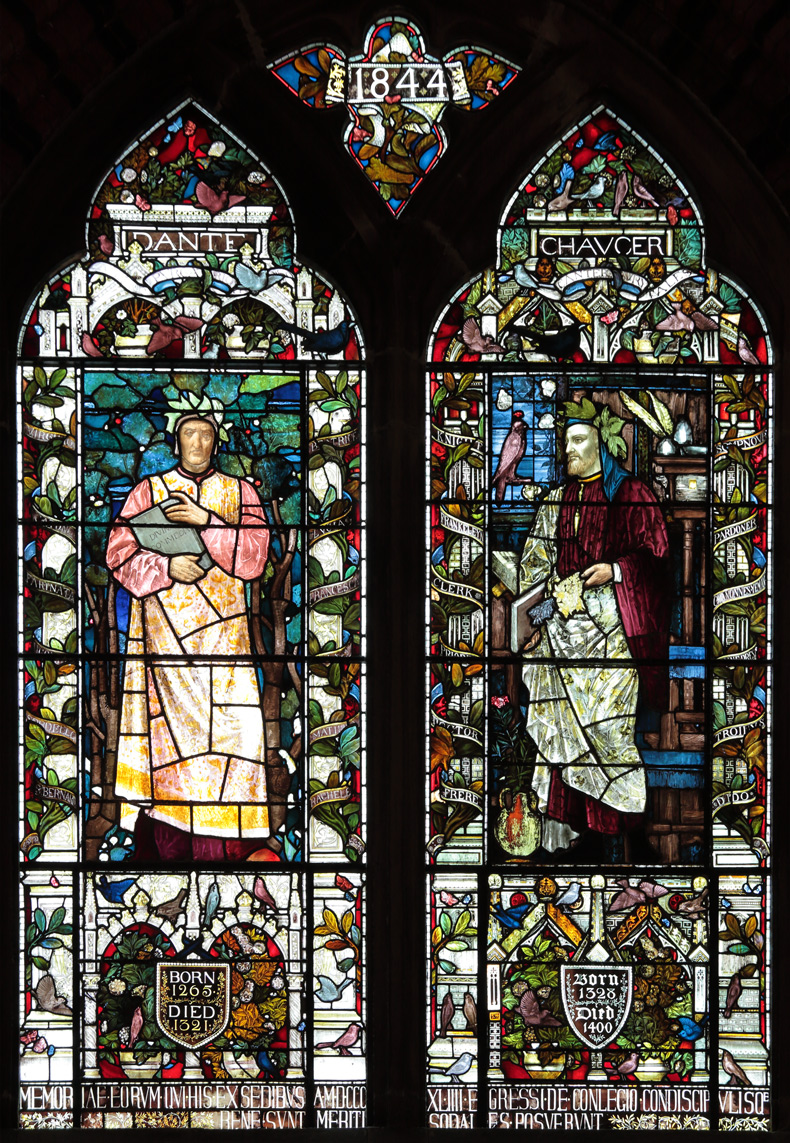

Dante and Chaucer (the Harvard Class of 1844 window), 1879. Memorial Hall, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Photo: © George Bryant

Bryant’s detailed accounts of many of Holiday’s magnificent windows point to the artist’s colossal artistic achievement; they also point to the fragility of the medium. Throughout the text, windows are subject to redecoration, relocation and destruction. The story of those in Christ Church, in particular, encapsulates the still uncertain fate of some of his greatest works. In 2000 and again in 2012, lightning strikes damaged the church in the Cobble Hill neighbourhood of Brooklyn, and the New York City Building Department closed it when stones fell off the building and killed a pedestrian below. Like many of the churches that commissioned Holiday in New York state, Christ Church was founded in the 1830s. Many cities in the north-east and in New York state were growing rich from the rise of industry in this period. It was with great civic pride that the residents of Cobble Hill commissioned a building in the Gothic Revival style by the British-born American architect Richard Upjohn. In 1842, the congregation consecrated and began to decorate their new church, a project that would continue for decades.

In 1885, the rector of Christ Church travelled to London and commissioned a new chancel window from Holiday, including Jacob’s Ladder/I am the Way and an Annunciation, followed by another in 1888. In 1916–17, the windows would be reconfigured by Tiffany, but much of his scheme was lost to fire in 1939. Fortunately, Holiday’s Annunciation survives; we can still see the statuesque Virgin Mary, clad in a richly decorated blue gown, who turns to face the Angel Gabriel with an expression both expectant and resigned – or we could if the building were not still contained by scaffolding and closed even to its congregation.

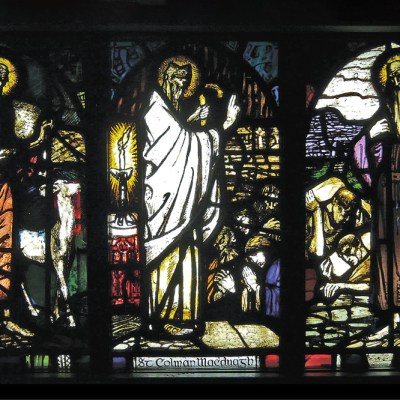

Boy Christ, (1877), Henry Holiday. Church of Our Saviour, Pennsylvania. Photo: © George Bryant

Other changes followed when the Brick Presbyterian Church moved to Park Avenue in Manhattan around 1940. It offered Christ Church its own Holiday window, Love, which had been commissioned in 1884 as a memorial to former New York governor Edwin W. Morgan. As Bryant puts it, ‘there is some poetic justice’ in the fact that a Holiday window replaced the burned Tiffany windows that had, originally, displaced Holiday’s earlier commission.

Bryant’s book joins others in a small but growing corpus of scholarship on 19th-century stained glass, including the trilogy of volumes by William Waters and Alastair Carew-Cox on Pre-Raphaelite work (Seraphim Press) and Peter Cormack’s Arts and Crafts Stained Glass (Yale University Press). Lund Humphries and the author are to be commended for investing time and resources in excellent photography. Stained-glass windows are difficult to record accurately and the brilliance of Holiday’s colour palette shines through in these reproductions.

Henry Holiday: His Stained-Glass Windows for Gilded-Age New York by George B. Bryant is published by Lund Humphries.

From the September 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.