On a recent visit to the new Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, I walked past the old school of fine art, a strikingly modern structure that resembles a factory more than a school. Nearby is the former school of applied arts, a slightly more expressive structure with hints of art nouveau.

Both buildings, now home to the Bauhaus University, are the work of the Belgian designer Henry van de Velde (1863–1957), who created a school based on a workshop system that would be taken over in 1919 by an architect named Walter Gropius. Like his successor, Van de Velde was not an architect of genius yet exerted a huge influence through teaching and writing and through the sheer breadth of his activities. But while Gropius designed the Bauhaus building at Dessau, which remains the defining image of modernism, Van de Velde left no such monument. His architectural career consisted of a succession of striking pavilions, interiors, display stands and temporary structures – none of which survive – as well as a few more permanent structures that are so varied in style and approach that it can be hard to see what connects them.

Van de Velde spent the first decade of his career as a painter, moving from a refined pointillism to Van Gogh-influenced swirls of skies, suns and straw. His book- and graphic-design work of the 1890s, in which sinuous curves and abstract patterns emerge from more figurative scenes, clearly lead to his furniture and domestic interiors (where those swirls translated into interlocking organic forms and complex geometries), less fluid than Parisian art nouveau, less severe than the Vienna Secession’s. He was astonishingly productive in virtually every field of design, from books to barber shops, houses to homewares.

The designer is certainly not a forgotten figure (he featured in every textbook and history I read as a student). The Continental Havana Company cigar store in Berlin (1899) is among the most familiar and remarkable of art nouveau interiors, even though it is long gone. The schools in Weimar (1908 and 1911) prefigured the idea of the art school as semi-industrial creative factory. Yet Van de Velde remains a rather elusive figure: never quite an innovator, always following in the footsteps of others, whether Ruskin and Morris, Victor Horta, or Josef Hoffmann; present in Zelig-like fashion at several transitional moments in the history of art and design. He was in Paris with the pointillists, sharing a studio with Signac. He was in Brussels as it became the crucible of art nouveau and in Berlin when it became a centre of European modernity. He was in sleepy Weimar as it enjoyed a renaissance as a centre of craft and industry and became the locus of the modernist revolution. Van de Velde died in Switzerland as the notion of Good Design – well-designed, functional objects – was on the rise; along with Max Bill (former Bauhaus student and founder of the ‘new Bauhaus’ school in Ulm), he was credited as its founder.

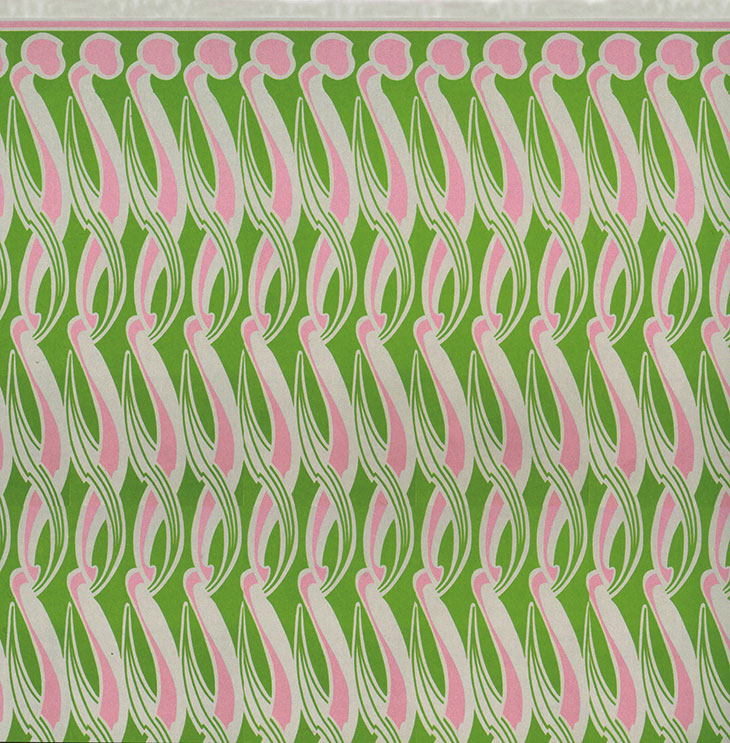

Wallpaper design, ‘Volutes’ (c. 1895), Henry van der Velde, published in Dekorative Kunst, no. 3 (1899). Courtesy Richard Hollis

He can also, however, seem like a curiously peripheral figure. Although he worked for the wealthiest individuals and companies of his day, his business was almost always shaky. Although he had been forced to resign from his post in Weimar during the First World War because of his Belgian citizenship, he was never forgiven by his countrymen for having spent most of the war in enemy territory. He became the archetypal European architect without a homeland.

Henry Van de Velde – The Artist as Designer is an admirable attempt to reintegrate its subject into the story of the birth of modernism. The renowned graphic designer and writer Richard Hollis (perhaps still best known for his collaboration with John Berger on the book Ways of Seeing) brings a professional eye to Van de Velde’s entire body of work. And what a body of work it is. From the early paintings of peasants in the fields and seaside scenes to designs for wallpapers, desks, food packaging, posters, memorials, coffee sets, cutlery, pottery, fashion and museums (the ‘original’ Folkwang, the Kröller-Müller), it’s difficult to think of any form the designer didn’t turn to. The buildings I remember from history lectures are here – Bloemenwerf, Van de Velde’s Arts and Crafts-influenced family home, in the southern suburbs of Brussels, and the low-slung theatre at the Deutscher Werkbund (a monumental and hugely influential structure that, oddly, lasted only six years). There are astonishing, swirling art nouveau interiors and blocky art deco buildings; chunky, bunker-like designs, and ugly bourgeois houses. It is a remarkable and very long journey, but Hollis makes it zip by.

Packaging designed by Henry van de Velde for the Tropon food company in 1898. Courtesy Richard Hollis

This is not a conventional biography like, for example, Fiona MacCarthy’s life of Gropius published earlier this year (see Apollo, May 2019). There may have been affairs and there were certainly traumas (including the loss of children) but Hollis doesn’t dwell on these. Instead he measures Van de Velde’s life through his works across all the media; everything seems to be illustrated, albeit often with rather small photos. Hollis’s analysis is acute, if occasionally a little forgiving. The essence is there in its title. Van de Velde may have espoused a modernist attachment to form following function, but there is always a hint of aesthetics overriding use in his work. He hankered after mass production but, like the Arts and Crafts designers before him, ended up ministering to the luxurious tastes of the rich.

There is, in this book, a slightly wistful tone about the conflict between the roles of a designer and an artist, between working to commission and fulfilling a personal vision. At the end of his long life, when he was respected but rather out of fashion, Van de Velde wondered if he should return to painting, or even dedicate himself to writing. In a way, this book by another designer embodies the conflicts, contingencies and complexity of a life combining art and design. To have one’s career encapsulated in a beautifully designed and affordable book seems a fine tribute. Twenty quid for all that work? Design for the masses.

Henry van de Velde – The Artist as Designer: From Art Nouveau to Modernism by Richard Hollis is published by Occasional Papers.

From the October 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.