For the British Antique Dealers’ Association (BADA), established nearly a century ago, its annual fair has become an essential tool. Now comfortably installed in a purpose-built marquee in Duke of York Square, the BADA fair celebrates its 25th birthday this year, and offers speedy consideration of some of the finest objects BADA’s members can field in its choice Chelsea location. It is an event that is not just popular among collectors. ‘Interior designers are an important community,’ chief executive Marco Forgione tells me, as well as ‘museum curators, art advisors, and individuals looking for outstanding art and objects to decorate their home’. To suit these 21st-century buyers, the fair has upped its game, rebranding itself with a new website and partnerships aimed at building new audiences – among them the British Institute of Interior Design.

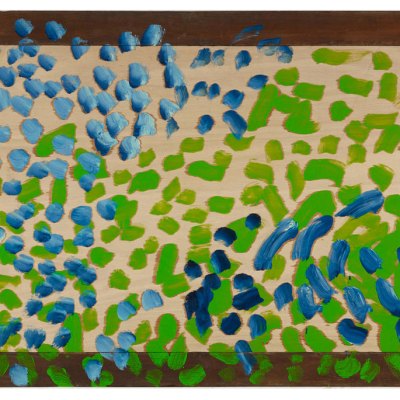

More than 90 dealers show objects that range widely across art, antiques, and contemporary design, embracing Old Masters, vintage jewellery and modern British painting – one of this year’s highlights is a large, vibrant canvas by John Hoyland (Alan Wheatley Art). While the authenticity of the objects on display goes without saying, vetting extends not just to their integrity. ‘They must also be beautiful, with excellent craftsmanship and notable provenances,’ Forgione insists. ‘BADA 2017 is not just about looking and admiring, it is about buying. It is all about an emotional engagement with objects.’

George III elliptical mirror (c. 1785), English, carton pierre. James WcWhirter Antiques, £11,800

It is clearly an approach that appeals to dealers. This year there are several new participants, including Mallett, Anthony Outred, Peter Petrou and joint exhibitors Alexander di Carcaci and James McWhirter. Petrou has commissioned the Irish designer and furniture maker Joseph Walsh to create a spectacular site-specific sculpture for the entrance to the fair (£245,000), and says of his eclectic display: ‘I have always bought in this spirit, but it is undoubtedly the new buyer’s idea of collecting. A lot of our clients will collect across the board, from Chinese and Japanese artefacts to Renaissance art and contemporary design. They are interested in visually arresting objects regardless of age.’

A pair of blackamoor figures (c. 1740), Dutch. Carcaci, £28,000

Carcaci is also exhibiting intriguing objects with complex back stories. There is a pair of Dutch early 18th-century blackamoor figures delicately carved with red hats, white cravats, knee-length buttoned tunics, and red socks, holding the tongues of stylised monsters. They would have been fixed to the wall and may represent Indian traders from the Coromandel coast in Tamil Nadu (£28,000). The dealership also has a precious red and white woven silk cloth, depicting a military camp with cannons and weapons, possibly woven to commemorate the Siege of Brussels in 1746 (£5,200). These complement James McWhirter’s painted and sinuous suite of mid 18th-century Italian furniture of around 1760 (£16,800) and, in a completely different mood, his elegant neoclassical carton pierre mirror, which dates to around 1785 (£11,800). Godson & Coles offers two exotic red japanned chairs from a famous suite of 77 pieces of furniture by the Clerkenwell-based master Giles Grendey. They were commissioned in 1730 by the Duke of Infantado for his castle in Lazcano, Northern Spain (price on application). Other new-found treasures include a rare George II walnut breakfront cabinet on stand, in the manner of Grendey. Made around 1740, it has a prestigious history in two major private collections before being bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 1964. Modern British paintings are displayed alongside.

Newcomer Anthony Outred brings a beautiful Roman cabinet dated 1650, the body crafted in ebony and rosewood, the drawers picked out in contrasting hardstone, with gilt urns, caryatids, and other mountings (£65,000). Outred tells me that Roman hardstone cabinets are rare because the Florentines, masters of pietra dura, monopolised the stone. Equally spectacular, but from a quite different culture, Thomas Coulborn & Sons shows an exuberant ivory-mounted Indian ‘Toilet Glass’ from the Punjab, dated 1850–60 (around £70,000). The town of Dera Ismail Khan, now in Pakistan, specialised in furniture ornamented with a type of elaborate, minutely incised lacquerwork – and this is a particularly fine example. ‘It will be part of a group of very interesting Anglo-Indian and colonial furniture and objects,’ Jonathan Coulborn tells me, ‘mixed in with some rare early oak furniture and objects from England.’

Sudeley Castle and St Mary’s Church, Gloucestershire, showing the effects of the Cromwellian demolition of 1649 (c. 1740s), Thomas Robins the Elder. Guy Peppiatt, £25,000

Another specialist in early English furniture, Paul Beedham, displays an extraordinary find – an elaborately carved oak overmantel almost 4m long, attributed to a Newcastle workshop of Dutch carvers. Dated around 1630, it once graced Hunwick Hall in County Durham but was thought missing since 1900, until it turned up at auction last year. Beedham recognised it from a photograph. ‘Something like this turns up once in a lifetime,’ he says. He is asking around £150,000. Howard Walwyn, a London-based clock specialist, exhibits a picturesque George II japanned quarter-striking moonphase longcase clock. Made around 1735, the movements are by Isaac Nickals of Wells, Norfolk (£85,000).

If English furniture has traditionally been a mainstay of the fair, another strength is British painting and works on paper. Indeed, there is a special loan exhibition of watercolours by Samuel Prout (1783–1852), a master of British architectural painting. Organised by John Spink, the display includes examples of Prout’s celebrated Venetian landscapes. Guy Peppiatt, meanwhile, has, among other English 18th- and 19th-century drawings, a charming and fanciful gouache by Thomas Robins the Elder (1715/16–70), depicting a Gloucestershire church and Sudeley Castle showing the dramatic effects of the Cromwellian demolition in 1649 (£25,000). Young dealer Archie Parker unveils a major trophy – a 1789 painting of two hack horses, sold by the Huntington at Christie’s New York last summer as ‘After George Stubbs’, which he has revealed to be a genuine work by the master (£750,000). Alan Wheatley, a modern British specialist with a leaning towards abstraction, shows paintings by Ivon Hitchens, Graham Sutherland and Alan Davie, alongside his vivid Hoyland (£95,000).

Tête d’oiseau (1950), Pablo Picasso. Sylvia Powell, £50,000+

Finally, there are ceramics by Picasso at Sylvia Powell, including a sharp-beaked, strongly incised Tête d’oiseau made in Vallauris in July 1950 (in excess of £50,000). Robyn Robb has gathered some fine examples of early English porcelain – including a Chelsea ‘Hans Sloane’ botanical plate, from 1755 (£8,750). Mark Goodger, of Hampton Antiques in Northamptonshire, has an array of beautiful antique boxes and accessories, including a papier mâché tea caddy by Henry Clay (£9,500), who patented the papier mâché manufacturing process in 1773. Clay typically decorated his caddies with Etruscan and landscape scenes, but this example of around 1795 displays wave-buffeted ships under stormy skies. While it is an object to set the heart of any tea-caddy collector racing, its singularity and the high quality of the painting will appeal to a much broader audience.

BADA takes place at Duke of York Square, London, from 15–21 March.