From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

There aren’t too many round museums out there – it’s not easy to hang paintings on curved walls. But maybe there should be more. The two most conspicuous examples in the United States, the Guggenheim in New York and the Hirshhorn in Washington D.C., are also intriguing places to see modern art, their centripetal spatial dynamics imparting a certain force to the viewing experience. As it happens, they also share a history. In 1962 it was an exhibition of modern sculpture from the collection of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, arranged along Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous spiral ramp at the Guggenheim, that brought the art-loving mining magnate to public attention.

Hirshhorn had emigrated from Latvia to the United States at the age of six; by 16 he was working on Wall Street as a stockbroker. Canny investments, especially in Canadian mineral rights, gave him the means to assemble one of the era’s great collections, ranging from 19th-century American painters – Thomas Eakins among them – to emerging talents such as Willem de Kooning. Unusually for a private collector, he had a particular interest in sculpture, and was friendly with such figures as Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti. After the Guggenheim’s presentation of these holdings, he was avidly courted by S. Dillon Ripley, then secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Hirshhorn soon agreed to donate his holdings to the government, along with an endowment for a new museum. Reputedly, he liked the idea that a poor Jewish kid could grow up to have his name on the National Mall.

When the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden opened, in 1974, it was the first modernist building on the otherwise neoclassical National Mall, predating I.M. Pei’s East Building for the National Gallery of Art by four years. That alone would have made it controversial, but the design by Gordon Bunshaft, of the firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, made it positively shocking. Set atop four massive piers is an enormous drum, 231 feet in diameter; the Guggenheim’s main spiral could fit neatly into the central courtyard. The building was sometimes compared to a UFO coming in for a landing, and more frequently to a fortress, with its horizontal window akin to the firing slot of a gun turret. ‘Not a particularly friendly comment,’ as critic Paul Goldberger noted, ‘but then, this is not a particularly friendly building.’

That may be so, but thanks to its location on the Mall, the Hirshhorn is actually far more public-facing than any of its peers. It is one of very few major art museums in the country, and the only one devoted to modern and contemporary art, that is entirely free. It is also visited by a genuine cross-section of the public – more than 700,000 of them last year. If any US institution has the chance to bring new audiences to its subject, it is this one. And if its founding collection, typical of its time, focused almost exclusively on white men, today its programme is as diverse as America itself.

This transformation is the subject of the Hirshhorn’s current survey exhibition, ‘Revolutions’, held on the occasion of the museum’s 50th anniversary (until 20 April 2025). More than 200 works are included, many from the founding collection, punctuated by recent acquisitions of contemporary art. It’s a show about then and now, and continuities and disjunctions across time. That theme is announced in no uncertain terms on the opening wall, where a typically ravishing society portrait by John Singer Sargent – among the oldest works in the collection – is hung alongside a sensitive depiction of a Black woman in a cobalt blue dress, painted by the Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo in 2020. More than a century separates these two pictures. Yet they share a typology, and a conviction that a single artwork can conjure something larger than itself.

Actually, 2024 is a double anniversary at the Hirshhorn. Melissa Chiu is marking her tenth year as director, having arrived in 2014 from her previous position at the Asia Society in New York City. Despite having to navigate the fathomless sublime that is the Smithsonian bureaucracy, as well a nearly two-year closure during the pandemic and the perpetually turbulent politics of Washington D.C., she can claim a formidable list of accomplishments. Annual attendance has doubled, as has the size of the board of trustees. The museum entrance has been beautifully redesigned by the Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto – an imaginative choice, given that he is best known as a photographer. In an age of generally underperforming museum apps, a mobile guide called Hirshhorn Eye (‘Hi’ for short), introduced in 2018, impresses for its ease of use and depth of content. And that collection has grown and diversified considerably, most recently through a gift of 141 contemporary Chinese photographs from the New York-based collector Larry Warsh, recently on view in the exhibition ‘A Window Suddenly Opens’.

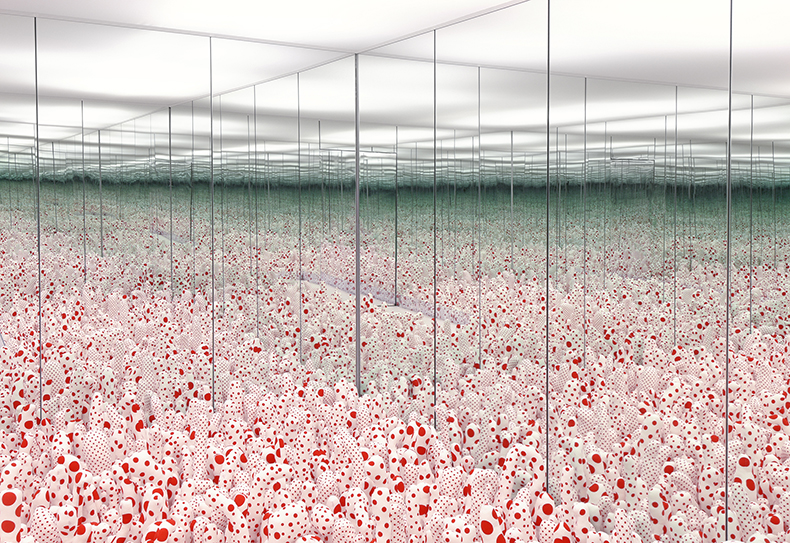

If one had to point to a project that has most defined Chiu’s directorship, though, it would unquestionably be ‘Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors’, presented to rhapsodic public response in 2017. The exhibition was such a runaway success that it is hard to recall a time when these mirrored environments were considered marginal to Kusama’s practice – a kitschy extension of her earlier maximalist abstraction. The Hirshhorn revised that script, presenting six of the chambers to show the full range of Kusama’s effects. In short order, the show became the hottest ticket in town and a citadel of avant-garde seriousness found itself one of the most Instagrammed places on earth.

The Kusama effect remains controversial. Quite apart from the social mediatisation of high culture (a ship that has definitely sailed), there is the more fundamental issue of whether immersive spectacle is a good thing for museums, or whether that sort of thing would be better left to Hollywood. Chiu professes herself agnostic on this question, but makes a point that can easily be lost in the debate: the real institutional impact of ‘Infinity Mirrors’ came only in the long term. ‘They came for Kusama,’ she says, ‘and stayed for Duchamp’.

A principle of ‘radical accessibility’, therefore, has animated the Hirshhorn throughout Chiu’s directorship. One of the first projects she green-lighted was ‘Processions’, a four-part collaboration with the Chicago-based artist Theaster Gates. The first of the events was particularly memorable. Titled ‘The Runners’, it was held in September 2016, in conjunction with the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Student athletes from Howard University circumnavigated the museum’s ring-shaped, third-floor galleries at a brisk jog, with Gates and his fellow Black Monks of Mississippi providing gospel-inflected song in accompaniment. The performance was moving in all senses of the word. An improvised activation of a normally contemplative space, it could also be read in emotional terms, as disturbing, hopeful, or both – what were these young Black people running from, or towards?

Gates’s activation of the galleries also confirmed something that Chiu and her curators had already been thinking: the Hirshhorn’s most effective projects, whether inside the building or out, exploit its unusually forceful architecture rather than fighting or simply disregarding it. That had been true of Krzysztof Wodiczko’s epic projection on to the building in 1988, one of the most famous public artworks of its day (the project was restaged by the Hirshhorn on its 30th anniversary), and it had again been true in 2011, when 102 of Andy Warhol’s Shadows paintings – his late, great, statement on mortality – were presented in an uninterrupted sequence around the gallery, inescapable as death itself. Circular thinking is also crucial to Mark Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge, commissioned by the Hirshhorn in 2017, and by any standard one of the most consequential American works of the 21st century. Much could (and has) been said about this monumental cycle of eight paintings. They curve around the third-floor gallery walls in the manner of a 19th-century cyclorama, which is no coincidence, as they were inspired by one that depicted the same event – the failed Confederate assault that marked the turning point of the Battle of Gettysburg and arguably the whole American Civil War – completed by the French artist Paul Philippoteaux in 1883.

Bradford responded not just to the enormity of Philippoteaux’s cyclorama – 13m tall, it is now preserved at the Gettysburg National Military Park – but also its almost cinematic fusion of fact and fiction. Using his signature technique, he layered printouts of its scenes together with rope, paper and paint, then selectively peeled back through the morass. The result is a distressed and disjunctive surface, a deconstructivist equivalent to Maya Lin’s famously mute Vietnam War Memorial, just a short, reflective walk away along the National Mall. As an endless topology of torn narrative, it is a perfect metaphor for American history, and given the Civil War’s centrality to ongoing conflicts about race, regional identity and competing ideals of freedom, also a powerful statement on the present day.

One question Chiu must get a lot – I certainly wanted to know – is how long Bradford’s masterwork will remain in place. At least for now, it is impossible to imagine it being removed; it would be like the Reina Sofía taking down Guernica. (The museum has two other long-term, site-specific installations, by Laurie Anderson and Barbara Kruger.) This raises an interesting question: how long is ‘the now’? On its 50th birthday, the Hirshhorn is responsible for about twice as much art history as it was when it was founded. Many of the works in ‘Revolutions’, which once seemed so radical, now feel remote, and require careful explanation so that visitors can understand their significance. How should a museum devoted to contemporaneity, like the Hirshhorn, steward artworks that become historical the moment they’re installed? How can it plan for the long term while still being responsive to the moment?

There’s no simple answer to these questions. To the extent that Chiu has one, it is to expand the theatre of operations. At the outset of a planned revitalisation of the building and its campus – a project that has been jointly awarded to SOM (Bunshaft’s firm) and Selldorf Architects – the Swiss artist Nicolas Party covered the necessary scaffolding with a huge mural, depicting faces peering out from behind colourful curtains. Hiroshi Sugimoto has been invited to extend his earlier work at the museum entrance, now advising on the layout of the surrounding sculpture garden. One working principle of this development is to position more audience-friendly works at the garden’s perimeter, with more challenging abstract sculpture closer to the centre.

At the same time, the Hirshhorn has involved itself in less conventional undertakings, including a reality TV show. The Exhibit: Finding the Next Great Artist, jointly produced with MTV and Smithsonian Channel, aired last year to an audience of millions. As is usually the case, there wasn’t much actual reality involved; the proceedings were hardly an accurate representation of how artists work (the seven contestants were asked to respond to a variety of set briefs in a limited time, and were then judged by a panel of art world celebrities). It was good fun though, and excellent promotion, with the Hirshhorn featured throughout and Chiu herself gamely appearing on screen – such is the job description of the 21st-century museum director.

Another, far more serious outside-the-walls initiative came about in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer in 2020. This horrific incident prompted all public-facing American institutions, museums included, to clarify their commitments to racial justice. Few found a response appropriate to these charged circumstances. The Hirshhorn was an exception, partnering with the Smithsonian American Art Museum and 11 other institutions around the world to organise a free, 48-hour streaming of Arthur Jafa’s indelible Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), a hard-hitting video work about racial violence in the United States. At a time when the Smithsonian was still closed due to Covid restrictions, it was the very definition of ‘radical accessibility’: not just a gesture, but a real service to the general public, transmitted through the medium of art.

Fifty years in, the Hirshhorn has reimagined itself in ways that its founders could scarcely have anticipated. Today it is not just a museum, but a performance stage, a broadcaster and, at times, a public sculpture. Chiu is not alone in exploring such roles for her institution; a flexibility of approach has become almost obligatory in the 21st century. But there is something special about the way the Hirshhorn is doing it. It’s all too easy to think that cross-disciplinarity is inherently progressive, but both infrastructure and expertise are real and it’s unlikely that the public is always better served when its museums also try to be theatres and cinemas. Chiu and her team approach this seemingly forbidding building as a place to drop ideas into the world, allowing them to ripple outward. What will the next decade, and the next half century, bring to the Hirshhorn? It’s impossible to say. But right now, this is one museum that’s definitely on a roll.

‘Revolutions: Art from the Hirshhorn Collection, 1860–1960’ is at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., until 20 April 2025.

From the May 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.