The apple originated in the wild. But thousands of varieties have been cultivated over the centuries – and their many associations have been taken up by artists with relish. The apple can mean just about anything: temptation and the fall, innocence and knowledge, immortality and death, love and sexuality, fertility and decay. No wonder it’s provided such a windfall for artists – from Greek vase painters to Pop artists.

I am part of the team behind ‘Apples & People’, an online programme which explores different aspects of humanity’s connection to the history, science and culture of the apple. Over the next 18 months illustrated apple stories will be released online, centred on an Apple World Map that we’ve commissioned from the artist Helen Cann. Down the line we’ll also stage exhibitions in the apple-growing county of Herefordshire. But in the meantime, here are eight great art-historical apples to get your teeth into.

Dürer’s Adam and Eve

Forbidden fruit. The Garden of Eden is where the apple assumes its symbolic status in Western art as an emblem of temptation. The Bible doesn’t single out the apple, but in representing the Fall artists took up the domestic sweet apple as their enticement of choice. This 16th-century engraving by Albrecht Dürer leads us into the garden at the point of temptation, as Eve takes the apple from the serpent to give to Adam. Dürer’s Tree of Knowledge visually separates the figures of Adam and Eve, with a naturalism in stark contrast to their idealised human forms.

Adam and Eve (1504), Albrecht Dürer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Orchard Painter’s column-krater

The ancient Greeks cultivated extensive orchards, handing down the technique of grafting to the Romans. This vase, attributed to an early classical artist known as the Orchard Painter, may depict the Hesperides, the mythological nymphs charged by the goddess Hera with guarding the golden apples of immortality – a task they bungled when Hercules succeeded in smuggling some of the fruit from the garden. They could be troublesome, those golden apples: just think of the one that caused the Trojan War.

Terracotta column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water; c. 460 BC), attributed to the Orchard Painter. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Pomologia and Pomona Herefordiensis

‘Pomology’, or the study of fruit, reached new scientific and artistic heights in the 18th century as it became possible to produce hand-coloured engravings for lavish publications dedicated to recording different varieties of fruits. Johann Hermann Knoop’s Pomologia (1758) included beautiful illustrations of apple cultivars that appear to project from the page, so convincing is his use of perspective and shading. The Herefordshire-born horticulturalist Thomas Andrew Knight followed with Pomona Herefordiensis (1811), a treatise on England’s cider apple and perry pear varieties. The illustrations record the minute details and blemishes observed on the gathered specimens by artists Elizabeth Matthews and Frances Knight, the author’s daughter.

‘The Red Must’, plate 4 in Thomas Andrew Knight’s Pomona Herefordiensis (1811). Cornell University Library, Ithaca

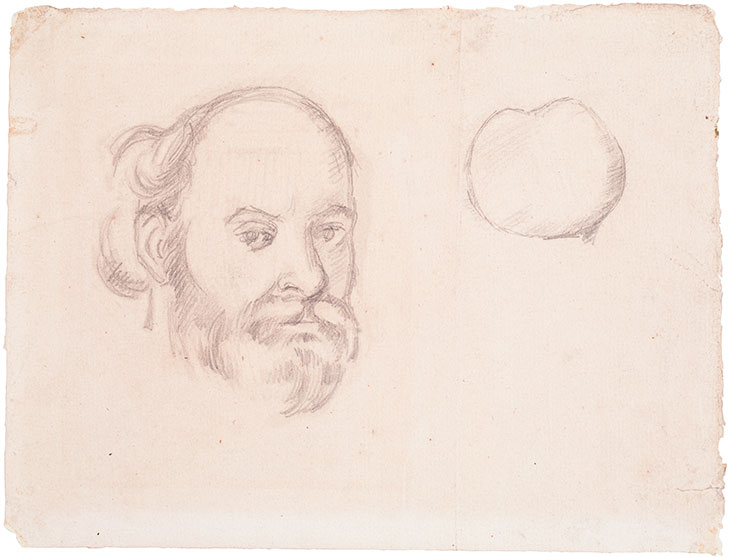

Cézanne’s apples

‘With an apple I want to astonish Paris’, Cézanne once said. In his still lifes, the artist radically reimagined how three-dimensional objects could be captured in paint, incorporating multiple viewpoints instead of a single perspective. So allured by the apple was Cézanne that, in one self-portrait, it seems not only to have lodged itself in his art but also in his mind: the drawing shows the artist’s head alongside an apple, as though they were commensurate forms. Perhaps Cézanne lived by his own dictum, often addressed to his portrait sitters – ‘Be an apple!’.

Self-portrait and Apple (1882–83), Paul Cézanne. Cincinnati Art Museum

Magritte’s Son of Man

A suspended green apple, most likely a Granny Smith, obscures the face of a man in a bowler hat: René Magritte, of course. The green apple seems to have shed most of its historical meaning by this point. It’s become the artist’s motif or identity, almost an empty vessel for the surreal contemplation of philosophical ideas. Magritte’s green apple was swiftly scrumped by pop culture: Apple Records, which The Beatles founded in 1968, was branded with an apple taken from Magritte’s Le Jeu De Morre (Paul McCartney had acquired the painting).

A green apple displayed at the opening of Musée Magritte, Brussels, in 2009. Photo: John Thys/AFP via Getty Images

Kiki Smith’s Red Apples

Eve and the forbidden fruit, Snow White’s poisoned apple: the association of women and apples most often spells bad news. Little wonder that women artists have been drawn to the fruit, often in an attempt to question established narratives and create their own mythologies. In Claire Partington’s ceramic sculpture Drunk Eve, the apple has given way to cider and a happily swigging Eve has discarded her fig leaf and silenced the serpent. Kiki Smith, meanwhile, has often strewn apples across gallery floors.

Red Apples (1999), Kiki Smith. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © Kiki Smith

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Apple Cores

Claes Oldenburg’s Apple Core sculptures update the vanitas tradition with a giant, decaying fruit. The withered core points to humanity’s imperfections – the once gleaming red apple now demolished, discoloured and discarded. Oversized and comical, the core also appears fragile and ready to topple. Its tough sculptural material (in the version at SFMOMA, steel) is at odds with its giant spongy appearance. Not one to bite into, then.

Installation view of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Geometric Apple Core (1991) at SFMOMA in 2016. Photo: Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

Barnaby Barford’s ‘MORE MORE MORE’

Barnaby Barford is ‘obsessed’ – his word – by apples, as is clear from his recent body of work, ‘MORE MORE MORE’. Exploring contemporary consumerism led him back to the idea of the forbidden fruit, to temptation and original sin. His almost Disneyesque Tree of Life holds an abundance of rosy red apples ripe for picking. Each china apple is hand-painted with text: a virtue, vice or human condition. It’s art that cuts to society’s core – exposing the good, the bad and the rotten.

Chaos (2019), Barnaby Barford. © Barnaby Barford

Antonia Harrison is programme curator of ‘Apples and People’, a partnership between the Brightspace Foundation, the Hereford Cider Museum and the National Trust in Herefordshire. It is being helped by a panel of some of the world’s leading apple experts – from USA, China, New Zealand, Italy and across the UK.