‘Draw Antonio, draw Antonio, draw and don’t waste time’. A sheet of paper housed in the British Museum makes Michelangelo’s views on art education very clear. He wrote this in response to a particularly poor effort by his pupil, Antonio Mini, who had attempted to copy a Madonna and Child, penned by Michelangelo for his edification. While a lot may have changed in art pedagogy over the last 500 years, the drawing remains, and if Michelangelo’s counsel fell on deaf ears back then, students have recently been taking his advice to heart.

Studies of the Virgin and Child (c. 1522–24), Michelangelo. Pen and brown ink, with copies in red chalk by Antonio Mini. The inscription reads: ‘Disegnía antonío disegnia antonío / disegnia e no[n] p[er]der te[m]po’ (‘Draw Antonio, draw Antonio, draw and don’t waste time’). © The Trustees of the British Museum

Over the past year and a half Sarah Jaffray and I have welcomed over 700 fine art students to the museum’s Prints and Drawings Study Room during more than 100 workshops. Generously supported by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation, it was our mission to show them drawings by artists from the 15th century to those working today, and to encourage close looking and drawing from them. The British Museum’s collection is a treasure house containing over 50,000 drawings and more than 2 million prints, but when we first met with tutors at London art schools, we were told that students were likely to be hostile to drawing, and more likely to keep a blog than a sketchbook. To remedy this, we provided sketchbooks to them all upon arrival, and spent months scouring the breadth and depth of the museum’s collection to provide them with the most exciting drawings we could find. The many discussions these works inspired informed the selection of an exhibition of 70 drawings – ‘Lines of thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to now’ – which will soon begin touring the UK, opening at Poole in September, before travelling to Hull and Belfast in 2017.

Studies for the Last Judgement (1534), Michelangelo. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The exhibition is structured around the premise of drawing as a thinking medium, with works grouped not chronologically, but according to the different types of thought process which drawing both records and demands. Initial thoughts, brainstorming, enquiry, association and development are all visible in drawings by artists working centuries apart, and bringing their work together demonstrates what can be learned from looking at masters of the past in the context of today. The exhibition will be the largest and most diverse group of drawings ever to be toured by the British Museum. One of the highlights is Michelangelo’s dynamic study for the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel (1536–41), in which the artist brainstorms various configurations of bodies in defiance of gravity, zooming in to focus on a figure, and then out again to take in the whole group. Similar evidence of a mind in motion is a bold drawing by Picasso, one of hundreds made in order to develop his incendiary masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). The final works relating to both drawings have such authority it is refreshing to imagine them existing in a state of flux, and to be party to the decision-making process covered up in the finished works.

A clump of trees in a fenced enclosure (c. 1645), Rembrandt. © The Trustees of the British Museum

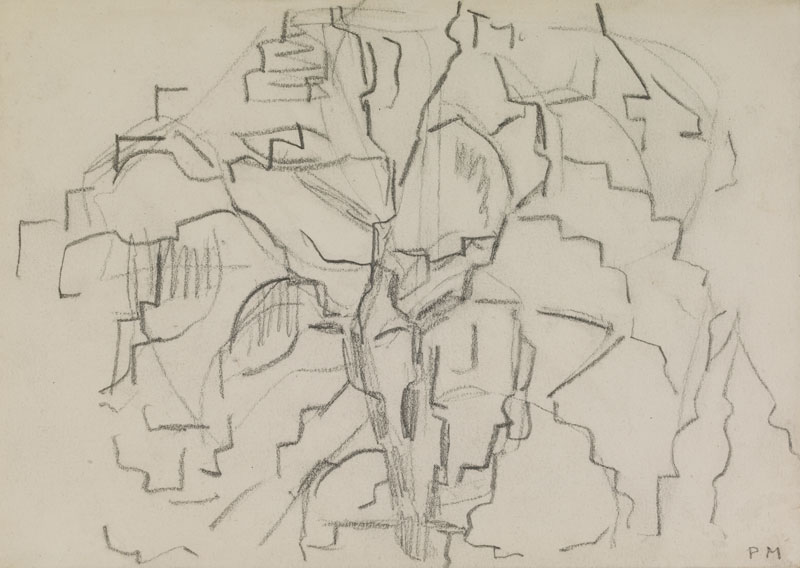

Tree study (1913), Piet Mondrian. © The Trustees of the British Museum

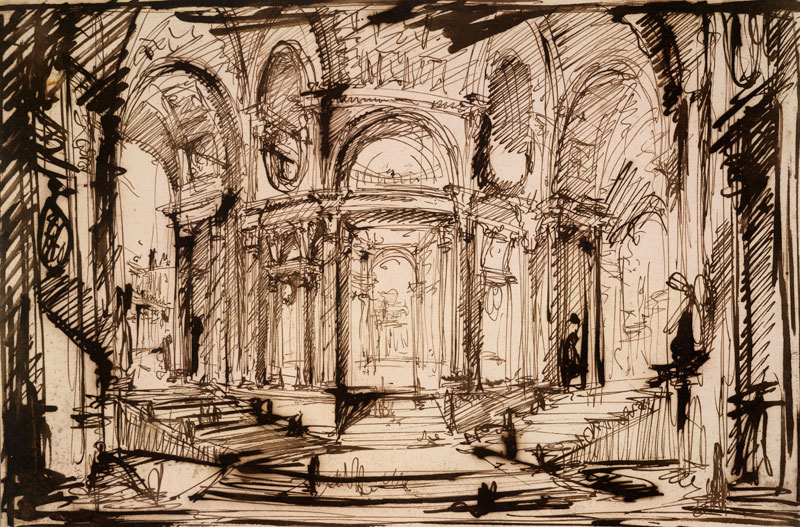

The juxtaposition of different drawings has resulted in numerous insights, for example in tree studies by Rembrandt and Piet Mondrian made nearly 300 years apart. Both Dutch painters made the studies en plein air for later development back in the studio. Both also used a schematic line to represent the relationship between solid and void in a tree’s boughs, a rhythm of vertical and horizontal marks which resonates across centuries. Another surprising correspondence is between a brooding pen drawing by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, and one by the Ethiopian-American artist Julie Mehretu. The latter has described her works as ‘narrative maps without a specific place or location’, built up as a palimpsest of marks in response to architectural views, plans and diagrams. Piranesi’s fantastical space was created in response to a set design by Filippo Juvarra (1678–1736). The artist altered the format but retained the latter’s innovative use of the scena per angolo double vanishing point, inducing a similar multiplication of perspectives.

Interior of a circular building (1752–60), Giovanni Battista Piranesi. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Untitled (2002), Julie Mehretu. Reproduced by permission of the artist. Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Drawing from drawings is not an attempt at reproduction, but an attempt to find something out – both about what is going on in front of you, and, as Henri Matisse noted, about one’s own work. He claimed that he made copies in the Louvre in order to find himself. The results of our workshops were surprising and invigorating; responses ranged from concrete poetry and oil painting to performance, yet all began with the act of drawing. While the exhibition has been formulated to appeal to art students across all disciplines, the quality and variety of drawings will appeal to anyone with an interest in the process of creation, and encourage them to take a leaf out of Michelangelo’s book.

‘Lines of thought: Drawing from Michelangelo to now’ is at Poole Museum from 3 September–6 November, and subsequently tours to the Brynmor Jones Library Art Gallery, University of Hull (3 January–28 February 2017), the Ulster Museum, Belfast (10 March–7 May 2017), the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe (25 May–17 September 2017) and RISD Museum, Providence (5 October 2017–7 January 2018).