When, in the 1970s, Howardena Pindell was working as a curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York – as the first African-American woman to serve in the museum’s curatorial department – she found she wasn’t always invited to events attended by her colleagues. ‘I was somewhat marginalised,’ she tells me. But there was an upside: ‘I could go home and work. I used the time wisely.’ During these evenings and nights, Pindell had been developing her own body of artistic work, some early examples of which are currently on display at Victoria Miro in Mayfair, along with more recent pieces.

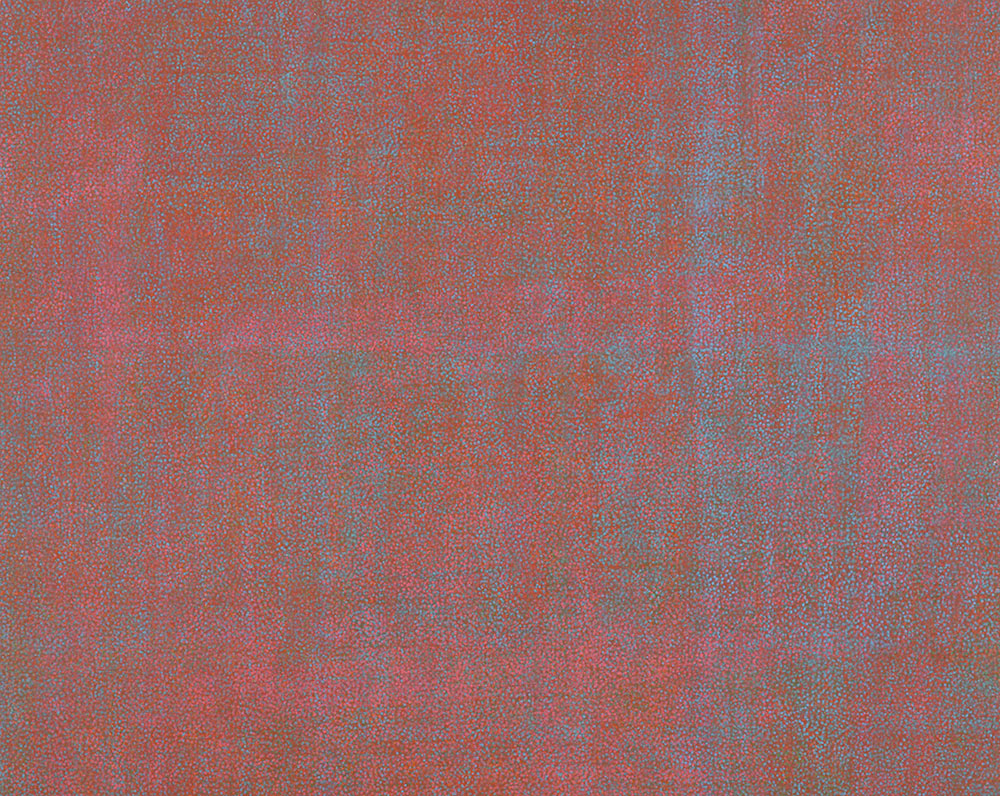

The earlier works are all paintings: large-format, horizontal canvases covered with layers of tiny dots, spray-painted on through stencils made of hole-punched card. The resulting images are shimmering, multi-hued – like a Seurat landscape without any figures or forms on which to focus. This is an intentional echo: ‘I love Seurat,’ Pindell says. ‘And someone has mentioned to me Monet’s water lilies.’ It was through her encounters with these artists, and many others, while working at MoMA, that Pindell developed her fascination with colour and its effects – something she had already read up on, when undertaking her Master of Fine Arts at Yale University in 1965–67. ‘I studied [Josef] Albers’ colour course. And so I understood colour more than if I had not taken that course.’

Howardena Pindell in her loft at 322 Seventh Avenue, New York, c. 1970–71. Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Victoria Miro, London/Venice; © Howardena Pindell

Until now, Pindell tells me, these paintings have only been exhibited once, soon after they were produced, at the A.I.R. Gallery – a woman’s co-operative that she co-founded in New York, before withdrawing in 1975 over tensions regarding the lack of interest in racial politics in the group of mostly white artists. Indeed, in the following years, Pindell found herself increasingly impelled to discuss race and identity not just in her activism but also in her art. The most well-known instance of this is her video Free, White and 21 (1980), in which the artist appears in two roles: herself, recounting the prejudice she has experienced, and the White Woman, who refutes these claims.

And yet, as the more recent works in the exhibition attest, abstraction remains an important mode for Pindell, and one which is not entirely divorced from politics. Dispersed among the large canvases are a series of small, three-dimensional pieces assembled from cut-out card circles, spirals and squares, graph paper and thread, and made between 2007 and 2010. Scribbled on some of the painted cut-out circles are a series of numbers, randomly assigned by Pindell. ‘I heard years ago that, apparently, during slavery they had slave tags that were circular, which would have numbers on them.’ She has also on other occasions recounted a disturbing childhood memory of, while travelling through Kentucky, coming across red circles stamped on mugs for use by non-white people. Are these the reasons for her use of circular chads, then, both in these and in the 1970s paintings? Not quite – or not entirely. The idea of the circle motif, Pindell recalls, was something she borrowed from a fellow student at Yale, Nancy Murata. But more importantly: ‘I like writing numbers, I enjoy punching holes, I enjoy painting.’

Untitled #59 (2010), Howardena Pindell. Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Victoria Miro, London/Venice; © Howardena Pindell

This joy in the act of making – ‘the physicality of it’ – is a driving force for Pindell, and one which is palpable in the laboriously wrought surfaces of her works. For all their geometric shapes, grids and repetition, they are a far cry from the minimalist aesthetic that was so fashionable in 1970s New York. ‘I was the opposite,’ Pindell says. ‘I kept thinking that the difference actually, at one point, between white art and black art is that white artists wanted to make work that looked like it was made by a machine. I call it “look mom no hands”. And then black artists wanted the expression of their personality, the touch, the texture.’

In recent years, as institutions have begun working harder to foreground African-American artists in their collections and programmes, new audiences have come to encounter Pindell’s work. She has been included in group shows such as ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ and ‘We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Woman, 1965–80’, which opened in 2017 at the Tate Modern and Brooklyn Museum respectively. When I ask Pindell about these exhibitions, she opens out the conversation into a wider discussion about the evolving relationship between politics and culture in recent decades. She contrasts the conservative backlash against radical art that characterised the culture wars of the 1980s and ’90s with the current political situation – which has, she suggests, had some fortuitous (if unintended) effects. ‘First of all, Trump’s not interested in culture, which is a great relief.’ Meanwhile, ‘some people, who were conservatives on the borderline, have moved further left – because he’s so atrocious and offensive to them. It has meant more money seems to be going towards Indigenous artists, First Nations artists, black artists, Asian artists.’

Untitled (1972), Howardena Pindell. Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York and Victoria Miro, London/Venice; © Howardena Pindell

So how does she feel about the increased exposure her work has received as a result of this shift? ‘There are some black artists who don’t want to be in shows that are labelled “black art”. I don’t mind it because I want people to be able to find me,’ Pindell says. And increasingly, they are: in 2018 she had her first retrospective at the MCA Chicago, and she is currently preparing for a show that the Fruitmarket Gallery in Edinburgh and Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge are organising, which will open in 2020. Here’s hoping that, what with this hectic schedule, there’ll still be time for Pindell to do what she loves best – writing numbers, punching holes, and of course, painting.

‘Howardena Pindell’ is at Victoria Miro, Mayfair, until 27 July.

Note (October 2021): Howardena Pindell’s exhibition scheduled for 2020 was delayed and will now open at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh on 13 November 2021 (until 2 May 2022); it then tours to Spike Island, Bristol and Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.