The first time I encountered the work of Huang Yong Ping was in an exhibition in Oxford in 1993. A huge structure of yellow silk and canvas occupied almost an entire room. To enter the tent, the visitor had to bend down and pass underneath a cage, in which up to a thousand locusts scuttled about – slowly shrinking in number as they were devoured by five scorpions. It had been made specially for the exhibition, David Elliott’s ‘Silent Energy: New Art from China’. It took its title, Yellow Peril, from the racist term coined in the late 19th-century to describe the ‘threat’ of a ‘yellow race’ invasion of the West. The work was an acerbic, visceral comment on migration and displacement.

Yellow Peril (1993), Huang Yong Ping. Installation view of ‘Silent Energy: New Art from China’, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1993. Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London; © ADAGP Huang Yong Ping

The disruption of space and use of live creatures are both typical elements of Huang’s work, which often juxtaposes culture and nature in order to confront vast questions about who we are, as historical and cultural ‘creatures’. A key figure of conceptual art from the People’s Republic of China, he pioneered a holistic, intellectual approach that drew on Chan Buddhism, Wittgenstein, Piero Manzoni and John Cage, among others. Or as Huang famously put it, ‘Chan is Dada, Dada is Chan’. His radicalism stemmed from his generation’s experience of the Cultural Revolution, when ‘Smashing the Four Olds’ was launched as a mass movement by Mao, who told millions of youth, ‘It is right to rebel!’.

Huang studied at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts from 1978–82. Like other artists who emerged from the academy in the first cohort after the Cultural Revolution, he was rebelling against ideological conformity, seeking a way out of a stifling art training consisting of copying 19th-century, European oil paintings and busts.

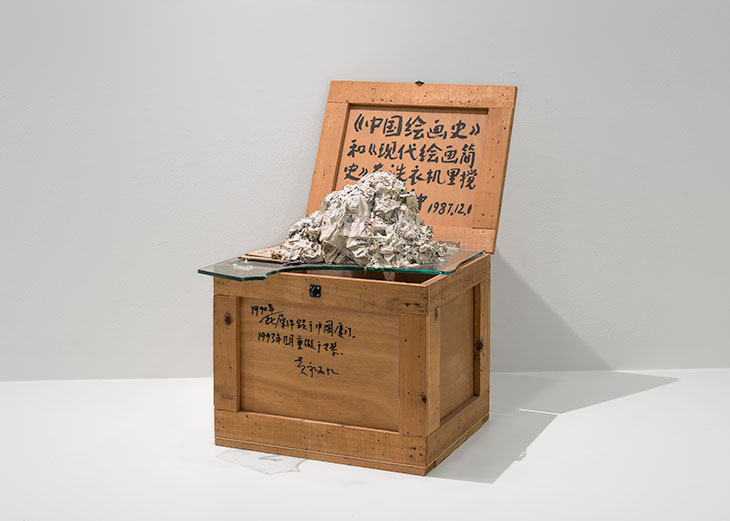

The History of Chinese Painting and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987), Huang Yong Ping. Installation view, ‘Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2017. Photo: David Heald/© Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2017; courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London

Huang’s achievement in his search for responses to China’s cultural conservatism in the mid 1980s came with the pulping of two books – a Dada-inspired strategy. The History of Chinese Art and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987) is a roughly compiled assemblage of pulped paper mounted on an old wooden box, inscribed by Huang in messy handwritten script. This work of ‘anti-art’, as Duchamp would have it, was a bold statement – breaking down and fusing together two art-historical traditions. Other important works made before leaving China were the collective action Xiamen Dada (1986) – performed by the Xiamen Dada group, which Huang had co-founded that year – and Towing Away the National Art Gallery (1988). In the latter, he proposed to pull the Chinese gallery off its foundations using 1,000 metres of hemp rope.

In 1989 Huang took a trip (which became a permanent move) to Paris for his participation in the seminal ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ exhibition at the Centre Pompidou. This, together with the support of the curator Hou Hanru, who collaborated with him on several occasions, led to his rise during the 1990s as a visible Chinese artist on the global circuit. Works like Yellow Peril were made with a new awareness of his status as an outsider in the West.

Empires (2016), Huang Yong Ping. Installtion view of ‘Monumenta’, Grand Palais, Paris, 2016. Photo: Joel Saget/AFP via Getty Images

Huang became a French citizen in 1999, the same year he represented France (alongside Jean-Pierre Bertrand) at the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999 – a clear sign that he had arrived on the international art scene. After that, he continued to produce many memorable works such as the gargantuan Empires, created for Monumenta (2016), consisting of an 130-ton aluminium snake surrounded by tall islands of stacked shipping containers in the great space of the Grand Palais. At the time, he declared, after 27 years in Paris: ‘I am still an outsider’.

Huang always had the air of a boffin, exuding a nerdy curiosity about the world, which he approached as a kind of mathematical quest. He was also wonderfully down-to-earth and straightforward. His death is a sad loss to the art community across China, Europe and the rest of the world, only mitigated by the considerable legacy he leaves in a body of work that is philosophically challenging, ambitious in scale and visually exciting. Long may they be appreciated.

Katie Hill is programme director of the MA in modern and contemporary Asian art at Sotheby’s Institute of Art.