A town that has, in its centre, a street called the Land of Green Ginger surely cannot fail to be interesting, but this intriguing name is nowhere near as old as the much bombed and much abused city of Hull itself. Properly called Kingston upon Hull since the reign of Edward I, and situated where the river Hull meets the wide Humber, it was one of the most important ports in medieval England, with strong trading links with both the Baltic and the Mediterranean. Given its cosmopolitan commercial past, it is therefore depressing to learn that Hull voted 67 per cent for Brexit in the wretched EU referendum. But Hull, like other parts of northern England, long suffered from neglect by government as well as industrial decline, its sense of isolation exacerbated by being geographically out on a limb, way to the east in the old East Riding of Yorkshire.

No wonder that Hull made a bid to become this year’s UK City of Culture, hoping that the accolade might bring regeneration and prosperity as it has done for both Glasgow and Liverpool. There is certainly culture here already, represented above all by the Ferens Art Gallery, which was given to the city by the great eponymous benefactor, politician and industrialist, who built up Reckitt & Sons, local manufacturer of household goods. A swish, fashionable Beaux Arts classical building of the 1920s, recently revamped and enlarged, it faces Queen Victoria Square, now the heart of Hull, with the Edwardian baroque City Hall on one side and the unusual Victorian Italianate former Dock Office, now the Maritime Museum, on the other.

Others must extol the collection of the Ferens. But Hull is also well worth visiting for its architecture. As can be appreciated from the Pevsner Architectural Guide to the city by David and Susan Neave, despite everything Hull can boast a wide range of distinctive buildings – some of national significance. There are two medieval churches, and there are still buildings dating from the 17th century, notably the ‘Artisan Mannerist’ red brick house in the old High Street in which one local hero, the great anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce, was born. Much more is left of Georgian Hull, though rather less than when Ivan and Elizabeth Hall published their book on the subject in 1979. There are fine terraces, some miraculously surviving Georgian warehouses and, above all, the 18th-century buildings of Trinity House.

Most of the buildings, however, that now give an agreeable, robust character to Hull, date from the reigns of Victoria and Edward VII, when there was pride, prosperity, and a mercantile bourgeois civilisation. Testament to the last are the suburbs around Pearson Park with, in particular, a group of ‘Queen Anne’ houses by George Gilbert Scott Junior, wayward son of the great Sir Gilbert, who had family connections in Hull. Prosperity reached its highest in the years before the Great War, when the vast new monumental Guildhall was built to the designs of Edwin Cooper: its 32-column long side elevation would, as Sir Nikolaus Pevsner observed, ‘look convincing in an Italian city where they did their stile Vittorio Emanuele like that’.

After this high point, the story is of decline, beginning in the 1930s when the ‘stupid […] planning folly’ (Pevsner) of filling in the Queen’s Dock to make a banal park was perpetrated. Then came the war, with devastating bomb damage, followed, inevitably, by a Plan (by Sir Patrick Abercrombie), with ruthless proposals for further clearance and new roads which, mercifully, remained largely unexecuted. Instead, the area between Queen Victoria Square and Paragon Station was rebuilt in a genteel, vaguely classical manner that today seems a model of its kind. Elsewhere, however, planning decisions led to blight and desolation, now interspersed with modern architectural rubbish. How several buildings in the Market Place that survived bombing could have been destroyed two decades later, some to make way for a wall of brown mirror glass facing the parish church, defies comprehension.

For Holy Trinity – to be elevated to minster status in May – is one of the wonders of Hull and Yorkshire. Vying with St Botolph’s in Boston, Lincolnshire, and St Nicholas’s in Great Yarmouth to be the largest parish church in England, it is a masterpiece of late gothic – decorated and perpendicular – and conspicuous for the early use of (red) brick. Spacious and logical, with big windows with flowing tracery, transepts and a noble crossing tower between aisled chancel and aisled nave, it comes, as Pevsner wrote, ‘close to the English late medieval ideal of the glass-house’. Inside, there is, or was, an impressive sea of dark woodwork, with the chancel stalls dating from Gilbert Scott’s careful restoration and, in the nave, pews with vigorous and imaginative poppyheads carved by George Peck and dating from the earlier restoration in the 1840s by H.F. Lockwood. Unfortunately, the City of Culture status has been used as an excuse for a gratuitous scheme to remove many of the Victorian furnishings and to place on rollers those pews allowed to survive.

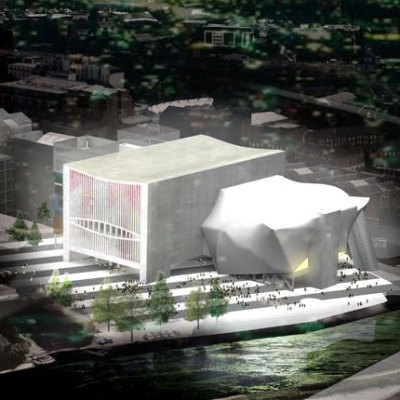

Holy Trinity is the earliest of Hull’s great public buildings. Not far away, across the river Hull, is the latest, and it best represents the city’s revival and escape from decline and mediocrity. Seeking to erect an ‘icon’ to achieve the mythical Bilbao effect, some imaginative councillors came up with the idea of taking advantage of the millennium to build a large aquarium, or, rather, ‘subquarium’. The site is the promontory where a citadel once stood. The architects chosen, by competition, were Terry Farrell & Partners. The result is an extraordinary, unprecedented structure that rises dramatically at the sharp apex where the two rivers meet. Unlike, say, the creations of the late Zaha Hadid, which tend to be blobs or heaps unrelated to context, the Deep (as it is called) both responds to the site and is full of intriguing and powerful resonances. Angular, sloping, and clad in various metallic textures, it might be a geological outcrop, or a whale rising from the deep (Hull once being a major whaling port), or a glacier. The inspiration referred to by Farrell is The Sea of Ice (1824), that dramatic painting by Caspar David Friedrich.

As architecture, perhaps the Deep is not wholly satisfactory as the composition rather collapses when seen from the rear. Also, it is a metal shed, which cannot but fail to express the nature of the interior – necessarily an affair of water tanks and ramps. But its zoomorphic form has given Hull something distinctive, original and unique, and it is surely one of the best of the millennial cultural monuments. Although it opened as long ago as 2002 (thanks to European Regional Development money as well as millions from the Millennium Commission), it may be too early to say how far it has helped regenerate the city. One problem is that between the Deep, and Holy Trinity and the Old Town there remains a divide. As noted in the 2002 book about the Deep, ‘crucial to the plan […] is the removal of the ghastly barrier of the 1982 southern ring road [Castle Street]’. But it is still there, still a barrier. Culture still has a way to go in Hull.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.