From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

If there’s one thing that sums up the awkwardness of the Humboldt Forum, Berlin’s new flagship museum complex, it’s the black flagpole that rises up through the building’s central stairwell. Statue of Limitations, a bronze sculpture designed in 2018 by the Seoul-born artist Kang Sunkoo (b. 1977), is intended to be a statement – as the Humboldt Forum’s own website tells us – against ‘colonial injustice’. The giant flagpole rises from the ground floor to the building’s ceiling two storeys above, displaying the bottom half of a flag (also black) before it is abruptly cut off. The remaining part of the flag, which is revealed to be at half-mast, will be installed in a part of the Berlin district of Wedding known as the ‘African quarter’ – so called because the streets there were mostly named after parts of Africa that Germany once colonised.

The lower section of Kang Sunkoo’s ‘Statue of Limitations’, designed in 2018 and installed in the central staircase hall of the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, in 2021. Photo: David von Becker; © Kang Sunkoo/SHF

The sculpture is Sunkoo’s comment on the building that surrounds it: the Humboldt Forum is housed in a reconstruction of the Berliner Schloss, a baroque palace that was once home to the Hohenzollerns, the Prussian – and later German – imperial dynasty. It was here, for instance, that Kaiser Wilhelm II resided as the German Empire carried out a genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples in what is now Namibia, between 1904 and 1908. As the flagpole rises to the top of the building, it encounters a collection of statues of Hohenzollern monarchs, on a second-floor balcony that overlooks the stairwell. To avoid them seeming triumphalist, the statues have been positioned out of alignment: some stand at right-angles to one another; some are human-sized, while others are miniature. The statues have had a note appended at Sunkoo’s request, pointing out the colonial possessions acquired by different monarchs.

In the foreground: statues of Joachim I Nestor (1484–1535; left) and Johann Cicero (1455–99; right), Electors of Brandenburg, installed in the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. Photo: Cordia Schlegelmich; © Stiftung Preussische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenbrug/Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss

The intention is to surprise visitors, in a part of the building that people can wander in and out of for free; a chance encounter that will make them reflect on the uncomfortable aspects of the palace’s history – and by extension, that of Germany. But in doing so, it risks pleasing nobody. For some, the Humboldt Forum (named after the brothers Alexander and Wilhelm, Germany’s celebrated Enlightenment intellectuals) is an inherently reactionary project: the effort to physically restore a major symbol of German power and empire overshadows any progressive aims. Sunkoo has already had to deny publicly that his work is a ‘fig leaf’. For others, it is not conservative enough: in September, one Humboldt Forum board member – Marc Jongen, an MP with the far-right Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) party; board members are drawn from various parts of the political spectrum – condemned the German president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, for the ‘guilt and shame rhetoric’ of his speech at the building’s opening ceremony.

This, however, is exactly the kind of clash that the Humboldt Forum’s director, Hartmut Dorgerloh, says he welcomes when I visit in November. ‘We want to be first in the Olympics of conflict,’ he proudly tells me, explaining his hopes that the Forum will become a ‘catalyst’ for wider debate in German society. But does the project generate more heat than light?

The Humboldt Forum has been a controversial prospect since before it contained anything on display – before, in fact, the current building had even been constructed. The original palace, built in 1443 on what is now best known as central Berlin’s ‘museum island’, and expanded in the 17th century by the baroque architect Andreas Schlüter, was heavily damaged by bombing during the Second World War. In the 1950s, the East German government, which controlled the part of Berlin where the palace stood, decided to demolish it, eventually replacing the building in 1976 with its own Palace of the Republic, a modernist cuboid with bronze-mirrored windows that housed the GDR’s parliament, as well as a public leisure complex. After reunification, this too was demolished – ostensibly because the building contained asbestos – leaving the site empty.

It was a private businessman, a tractor tycoon from Hamburg called Wilhelm von Boddien, who launched a campaign to rebuild the former imperial palace. In the 1990s, he paid for the site to be covered in a tarpaulin that bore a life-sized image of what the reconstruction would look like. Other wealthy Germans joined him and, in the early 2000s, the German parliament approved plans for reconstruction: the deal was that private donors would pay for the facade, while the government took charge of what went inside.

From the outset, the project generated disputes. Advocates of reconstruction stressed that the project was aesthetic, rather than political – it was about restoring a masterpiece of northern European baroque architecture to Germany’s shattered capital. ‘Why must Berlin suffer from the Nazi times more than other German cities?’ Von Boddien asked the New York Times in 2018. ‘Why don’t we allow Berlin to be beautiful again?’ Others objected that to rebuild the palace was an inherently nationalist and conservative project. Some former Easterners, meanwhile, felt that their heritage – the GDR-era building – had been erased in the service of a new, unified Germany. The reconstruction attracted further criticism as it ran into delays and went heavily over budget: when the building was eventually completed, almost two decades later, it had cost more than 600 million euros.

Mandu Yenu throne with footrest, made before 1885 in the Kingdom of Bamum, Cameroon, installed in the ‘Colonial Cameroon’ display at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin. Photo: Alexander Schippel; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum/Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss

But it was one of the more innocuous-seeming decisions taken in the early days that has become the most controversial now. Having approved an essentially empty building, the German government decided that it would house items from state collections of non-European items: chiefly the Berlin Ethnological Museum, which holds collections from Africa, the Pacific and the Americas, and the Museum of Asian Art. The decision appeared to be far less of a political statement than, say, using the building to house part of the Federal government, which moved from Bonn to Berlin in the late 1990s. Besides, bringing the two museums – which were previously located in the outlying Berlin suburb of Dahlem, and attracted relatively few visitors – into the heart of the city’s tourist district would complement the collections of European and Classical art already on Museum Island. As Alfred Hagemann, head of the Humboldt Forum’s history of the site department, the curator in charge of the site’s history, tells me, at the time it seemed like ‘a nice idea’.

In the years since, however, collections such as these in Western museums – many of which were assembled during the era of European colonialism – have become highly politicised. Today, the need to acknowledge the violent circumstances in which many items were acquired (or stolen), and to discuss forms of redress including restitution is at the top of the agenda, including in Germany. Somewhat belatedly, Bénédicte Savoy – co-author of the landmark French report on restitution – was added to the nascent Humboldt Forum’s board, only to resign in 2017, complaining, among other things, of a lack of attention to provenance research.

For many people, the main sticking point was the building itself. Three of the four outer walls of the palace have been reconstructed as accurately as possible – mainly based on old photographs – with hundreds of stonemasons working on the facade’s carved decorations. (The fourth wall is a largely featureless modern grid, designed by the Italian architect Franco Stella, who has also fitted out the building’s interior in clean, if bland fashion.) The restoration is, as Hagemann pointed out to me, a work of art: some masons may have spent as long as two years on a single element. But for critics, it’s terribly misjudged. ‘Locating ethnographic collections in a Prussian castle is a complete mismatch,’ Savoy told the Art Newspaper recently. The building, she said, ‘is a symbol of German oppression, hegemony and colonialism’. Last month, the family of one donor, the banker Ehrhardt Bödecker, who died in 2016, asked that the Humboldt Forum remove his name from a collection of medallions honouring people who had given the project more than €1m, after he was revealed to have had a history of making far-right and antisemitic statements.

The dome of the rebuilt Berlin Palace, photographed in 2021. Photo: Stephanie Loos/AFP via Getty Images

One thing that has particularly upset critics was a decision to rebuild the chapel added to the roof of the palace in the mid 19th century, whose dome, topped with a golden cross and orb, bears an inscription which demands that ‘in the name of Jesus all of them that are in heaven and on earth and under the earth should bow down on their knees’. This declaration of might was the Prussian monarch Friedrich Wilhelm IV’s response to the revolution of 1848, and the revolutionaries’ demands for a constitutional monarchy – a retort that he obeyed no authority other than God’s. Today, sitting atop a former imperial palace that now contains some of the spoils of the empire, it seems even more jarring. When the dome and inscription was unveiled earlier this year, a protest group calling itself the Coalition of Cultural Workers Against the Humboldt Forum ceremonially dumped a papier-mâché replica of the cross and orb into the river Spree, which runs past the Humboldt Forum.

Until recently, the Humboldt Forum’s response to criticism has been ‘wait and see what we do inside’. A planned physical opening in December 2020 had to be transferred online, due to the coronavirus pandemic, but the building finally opened to visitors in July this year. Currently about a third of the galleries that house the collections from the Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Asian Art are open, while the building is also home to a branch of the Berlin State Museum – hosting an exhibition on ‘global Berlin’ when I visited – as well as displays scattered across the complex that tell you about the history of the site. (These include the ballot box in which the East German parliament voted for reunification, and the remains of statues from the baroque palace exterior, broken and blackened by war damage.)

Outrigger ship, late 19th century, from the island of Luf, installed in the ‘Oceania’ display at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, in 2021. Photo: Alexander Schippel; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum/Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss

The Ethnological Museum is home to perhaps the most sensitive exhibits of all. The 500,000 items, most of which are still stored at the original Dahlem site – it will remain open for research, while around 20,000 items will be on display at the Humboldt Forum once it is fully open – form one of Europe’s largest collections. Many items were taken by force, or under circumstances where the people who handed them over could not give meaningful consent. Among them is a large double-hulled boat from Luf Island, Papua New Guinea. It occupies a central position in the new museum, in a large hall to the side of the main galleries; the curators intended to display it as an example of an item that was taken with consent – until a recent book linked its acquisition to a colonial-era massacre. Alexis von Poser, deputy curator of the Ethnological Museum, tells me that they are now working with descendents of the boat builders: rather than asking for the original vessel back, they want the museum to help them build a new one.

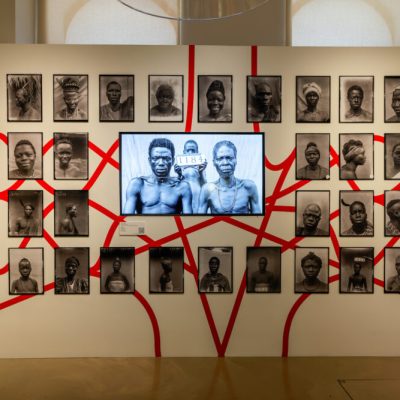

In its new setting, the Ethnological Museum is at pains to make its troubled history clear. Its first main room greets visitors with a quote from the US author Robin DiAngelo, proclaiming, ‘I have a white frame of reference and a white worldview’, as part of a display on the legacy of colonialism. This strikes an odd note, since DiAngelo, whose best-selling books are the favoured texts of corporate diversity initiatives, is often criticised by other anti-racists for making racism a question of individual psychology. A museum, by contrast, ought to be the ideal place for a conversation about the more complex ways in which power structures affect our behaviour towards one another.

The Ethnological galleries that are currently open focus on items from Africa and the Pacific. Many of these are displayed in what the curators call ‘open storage’: glass cabinets that hold dozens of similar items, in a way that mimics the shelves of a museum storage room, but which are available for the public to view. One such case, from the Frobenius collection of items taken from the German Congo before 1904, holds dozens of ceremonial metal blades and axes. In another part of the museum, a large case holding musical instruments from many different parts of the world is arranged to show visitors how Western collectors have categorised them by type – and how this differs from source communities’ ways of thinking about sound and music.

Indignation (2012) by Justine Gaga, installed in the ‘Colonial Cameroon’ display at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, in 2021. Photo: Alexander Schippel; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum/Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss

Interspersed among the older objects are contemporary artworks and displays intended to tease out the history of the collection – and the conditions under which it was assembled. One cabinet contains photos of items belonging to the Herero and Nama peoples, such as ceremonial robes. The originals have been sent to Namibia as part of a restitution process: rather than ask for the objects outright, the Ethnological Museum’s Namibian partners have asked to study them, so they can determine which objects, stolen from them by colonialists more than a century ago, are of value to the communities from which they originated. A room displaying objects from Cameroon – including a beaded, bright blue and red throne that once belonged to King Ibrahim Njoya, who ruled Bamum from 1886 until 1933 – includes an installation by the contemporary Cameroonian artist Justine Gaga. Pillars made out of gas canisters, of the kind many people in Cameroon use at home for cooking and heating, painted orange, blue, pink and turquoise, bear words such as ‘CAPITALISME’, ‘VIOLENCE’, ‘FONDAMENTALISME’ and ‘PRIVATISATION’. How the museum deals with its most contested items – its collection of Benin Bronzes, which Germany seems increasingly open to returning to Nigeria – remains to be seen, as the Nigeria gallery won’t be open until next year.

Von Poser hoped that the museum would be understood as more of a space for collaboration than inert displays. A set of carved wooden masks from New Ireland used in Malagan funeral ceremonies, for instance, were largely acquired with the consent of the owners – Von Poser says they had evidence that at least one was stolen, but that many were given away since the masks were traditionally discarded once the ceremonies were over. New Ireland’s current residents don’t want them back, but they are in touch with the museum because they want to examine the objects to revive traditional carving skills. This kind of collaboration, says Von Poser, is an example of how facing up to the colonial legacy ‘is about more than just restitution’. It’s not yet clear how intelligible this will be to visitors who aren’t lucky enough to get a guided tour, however: interactive video screens, intended to provide more information about the objects and the communities from which they come, still weren’t operational when I visited.

Installation view of the ‘Jain Art in India’ display at the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, in 2021. Photo: Alexander Schippel; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Ethnologisches Museum/Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss

At the Museum of Asian Art, the collections have again been arranged to be more open to the casual visitor. While the Dahlem site was very much a museum ‘by connoisseurs, for connoisseurs’, according to the curator, Martina Stoye, grouping items on display by school of art, at the Humboldt Forum they have been reordered. In the rooms currently open, which mainly display items from the Indian subcontinent, items have been grouped according to religion and arranged chronologically. In a room devoted to Buddhist worship (one central cylindrical cabinet holds dozens of Buddha heads), it is easy to see how devotional objects evolved from non-figurative carvings to figurative statues over several centuries.

The curators I speak to all seem a little uneasy in their new surroundings, keen to point out the limitations of the Humboldt Forum or where they would like to see things improved. Von Poser says that staff are committed to restitution where appropriate, and to working with source communities, but that it depended on resources. (A recent story in the German press revealed that the Humboldt Forum has only four paid staff working on provenance research.) To further such work, he says, ‘we need a societal agreement that this is important and worth spending tax money on’. It’s possible that money will be forthcoming: Germany’s new coalition government has just announced a commitment ‘to advance the reappraisal of colonial history’ by supporting research, as well as ‘dialogue with societies of origin’ and the restitution of objects.

Walking around the site, the overall effect is a little bewildering: at only a third capacity, it would already take days to look seriously at everything on display. There is a shopping mall feel to the building, enhanced by the jazzy, brightly lit signage in the building’s public areas. Stoye told me that she wasn’t sure if the mix of different museums would gel, but she appreciated the way in which visitors – there have been an estimated 350,000 since the Humboldt Forum opened in July; the site eventually expects around 3m a year – make chance encounters with objects and displays as they explore the site.

When I spoke to Dorgerloh, he said he hoped the Humboldt Forum would become ‘like a magnifying glass for Germany, to make aspects of our history and of our present more obvious’. The director was keen to stress the ‘forum’ aspect of the project – the palace courtyards are public spaces, open 24 hours, while the venue also contains events spaces that will host talks and performances. ‘This is something for the mainstream,’ he says. ‘It is not preaching to the converted. It is preaching to the people.’ Dorgerloh, who has been director of the Humboldt Forum since 2018, was formerly the curator of Brandenburg’s Prussian royal palaces and gardens – a perhaps unexpected background for such a contentious project, but one that he felt gave him good grounding in fielding pressure from both left and right.

‘My professional background is monument preservation, so this is obviously a central question,’ he says: ‘Why should we maintain these old buildings having no kings any more – or in a de-Christianised society, why should we maintain these churches, and so on. I think that the answer is very simple. We need the past for creating a future, and the future is not something that can be created while only reflecting the glorious past of your own nation, because we can no longer talk about national solutions for global problems.’ The Humboldt Forum, he suggested, could provide a ‘bridge’ – not just between past and present, but between rival camps in a divided society.

That is a laudable aim. Whether a giant, contentious architectural folly is the place to do it, however, is another question entirely. On leaving the Humboldt Forum, through a baroque portico, I noticed one of the ‘flashbacks’ – objects relating to the history of the buildings that have stood here over the centuries, which are now dotted around the site. Three pictures are displayed together, showing moments when this place was the focus of popular protest: a painting of soldiers fighting with demonstrators during the 1848 revolution; a black-and-white photograph of a demonstration outside the Palace of the Republic in 1968; and protesters holding pro-democracy banners on its front steps in 1989. The aim, perhaps, was to situate the Humboldt Forum within Germany’s democratic heritage. But the pictures looked terribly small underneath the heavy stone arch. To me, at least, it was a reminder that democratic energy often comes from outside institutions, rather than within them.

From the January 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.