In March 1918, the National Gallery director Sir Charles Holmes and the then Treasury adviser John Maynard Keynes travelled to Paris on a secret wartime mission to buy up masterpieces of French 19th-century art at knockdown prices from the posthumous sale of Degas’s art collection. They acquired 13 paintings by Ingres, Delacroix, Corot, Gauguin, Cézanne and Manet – including his Execution of Maximilian (1867–68) – and returned with £5,000 change from their £20,000 government grant.

The Execution of Maximilian (c. 1867–68), Edouard Manet. © The National Gallery, London

If you’re investing in artistic futures, don’t ask a dealer or a curator – ask an artist. This is the moral of the National Gallery’s exhibition ‘Painters’ Paintings’, which explores the collecting habits of eight painters – Freud, Matisse, Degas, Leighton, Watts, Lawrence, Reynolds and Van Dyck – through a mixed hang of 80 paintings that juxtaposes works they acquired with works they painted.

Chronologically the story starts with Titian’s The Vendramin Family (c. 1540–43/1550–60), once owned by Van Dyck, and ends with Corot’s Italian Woman (c. 1870), once owned by Freud. Artist collectors, it emerges, are driven by a mix of motives from compulsion to emulation. ‘I buy! I buy! I can’t stop myself,’ confessed Degas, while Reynolds regarded his acquisitions ‘as models which you are to imitate and at the same time as rivals with whom you are to contend’.

The connections between artist collectors and their ‘models’ and ‘rivals’ aren’t always clear. Degas, for instance, was a voracious collector of Ingres and Delacroix, but while a pair of pastel sky studies by Degas and Delacroix could almost be by the same hand, it’s harder to see what Degas absorbed from Ingres – although the pose of Oedipus in Ingres’s Oedipus and the Sphinx (c. 1826) could be that of a dancer about to tie on a shoe.

The Four Times of Day: Noon (c. 1858), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. © The National Gallery, London

Preliminary sketches were especially valued by artist collectors wanting to pry into their heroes’ working methods: with their patchworks of collaged additions, Rembrandt’s two studies for The Lamentation of Christ (c. 1634–35), once owned by Joshua Reynolds, seem to offer insights even into the master’s thought processes. Before the 19th century, artist collectors focused on Old Masters, but Reynolds made a rare exception for Gainsborough’s Girl with Pigs. Leighton was a good deal more adventurous, helping to form the British taste for Corot by acquiring The Four Times of Day (c. 1858) for Leighton House.

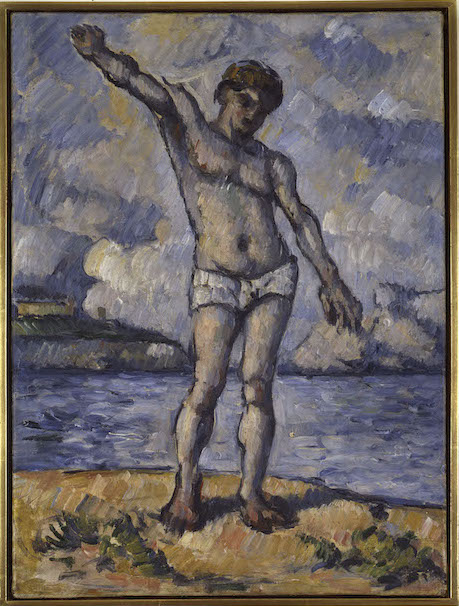

Bather with Outstretched Arm (1883–85), Paul Cézanne. Collection Jasper Johns. Photo: © Dorothy Zeidman

In terms of staying power, Corot steals the show as the perennial painter’s painter: his early Roman Campagna (c. 1826) hung in Degas’s bedroom and his late Italian Woman in Freud’s. His main challenger is Cézanne, represented here by two pocket masterpieces from the collections of Degas and Matisse. Degas owned the strangely magical little Bather with Outstretched Arm (1883–85) now in the collection of Jasper Johns, while Matisse owned the Three Bathers (1879–82) on loan from the Petit Palais, featuring a standing nude with hair hanging down her back. The painting’s pairing with Matisse’s bronze relief, Back III (1913–16), is the most telling juxtaposition in the show. Matisse credited it with having sustained him through his career, declaring: ‘I have drawn from it my faith and my perseverance’. If he was honest, he might have added ‘and my Backs’.

Three Bathers (1879–82), Paul Cézanne. Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris. © Petit Palais/Roger-Viollet

It’s hard to know what route to take through this exhibition. The catalogue works backwards chronologically from Freud, as it was the bequest of his Corot to the National Gallery in 2011 that gave the curator Anne Robbins the idea for the show. In the exhibition Freud is oddly squeezed between Van Dyck and Reynolds, but the core of the displays is the Degas collection, which fills two galleries. These might have been expanded into a fascinating exhibition on their own, allowing the British public to speculate on what that unspent £5,000 could have bought us.

Italian Woman (c. 1870), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. © The National Gallery, London

‘Painters’ Paintings: From Freud to Van Dyck’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 4 September.