From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

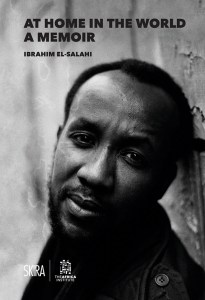

Born in Sudan in 1930, Ibrahim El-Salahi is one of the most important modernist artists of the 20th century. He is best known for his paintings and drawings, which integrate the refined strokes of Arabic calligraphy with African motifs and a fluency in European art traditions. He is a founding member of the Khartoum School, one of the most important centres of modern art in Africa.

At Home in the World presents the artist’s own account of his life for the English-speaking world. His memoir in Arabic was previously published in Sudan to coincide with his touring retrospective, ‘Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist’ in 2012–13. It begins with El-Salahi’s childhood in colonial Sudan and moves through different periods: in London, the Americas, Sudan, Qatar and Oxford (where he now lives). El-Salahi focuses on moments and experiences ‘that have stuck uppermost in my mind and from which I have learnt a great deal.’

A host of extraordinary people and interactions have shaped his views. Among the most revealing are the meetings he describes while travelling the Americas in the 1960s (as a recipient of a UNESCO Fine Arts Fellowship and Rockefeller Foundation residency). His recollections of meeting artists such as Jacob Lawrence are interspersed with encounters with ordinary people. He meets struggling Puerto Rican immigrants and spends an evening with a nervous young man about to join the paratroopers, anticipating deployment in Vietnam. Race and religion are also key themes. There is a vivid account of talking to Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, in Chicago. They discuss Sudan (where Muhammad had visited), Islam and the United States. He reflects on the struggles and contradictions of the American Civil Rights Movement and on being an African observer of these transformations.

El-Salahi also reflects on pivotal moments in his development as an artist. He describes, for example, his return to Sudan in 1957 (after studying at the Slade School of Art in London) and his puzzlement that all the works he produced were bought by Western expatriates. With an ethnographic eye, he investigates what images Sudanese people consumed and enjoyed. He finds them in Arabic calligraphy and African motifs of everyday life. These enquiries lead him to creating some of his most important works, such as Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I (1961–65; Fig. 1), which integrate ‘Arab’ and ‘African’ forms. Reborn Sounds encapsulates this mode of work – with its strong lines and negative spaces inspired by calligraphy and ghostly images of African masks. It is painted in oil and enamel on a Sudanese cotton called dammuriya, further invoking the past, tradition and place. El-Salahi recalls how his hands moved across the canvas ‘as if I had no will of my own and had been totally overpowered by this unknown spirit working within me.’ Despite its significance, El-Salahi notes that Alfred Barr Jr, in his role as director of collections, had been close to acquiring this piece for MoMA in the 1960s, but declined because of the quality of the traditional fabric.

Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I , (1961–65), Ibrahim El-Salahi. Tate, London

While El-Salahi is ‘at home in the world’, his life (and works) have been shaped by the cultural history, landscapes and political upheavals of his country of birth. But this relationship has not been straightforward. A turning point came when he returned to Sudan in 1972 (after a period working as Sudanese cultural attaché in London) to take up a role in the ministry of culture. Sudanese friends in London warned him against returning because of the tense political situation. After a failed coup, El-Salahi (wrongly accused of involvement in anti-government activity) was imprisoned for six months in 1975. Writing and drawing was banned, but he made drawings on tiny pieces of paper and buried them in the sand of the prison floor. He left the drawings behind in the sand, but carried with him the ideas he developed in prison and the practice of processing pain and trauma through art. El-Salahi describes producing a collection of abstract line drawings and poems (Prison Notebook, 1976) after he was released from prison but still under house arrest. He notes, ‘I must have tried through abstraction to make sense of why things unexpectedly happened to me, and to bring some order back…’

El-Salahi has not lived in Sudan since 1977, although he has been a prominent figure in the country’s cultural life and diaspora. He worked in Qatar (a role facilitated by his friend, the Sudanese author Tayeb Salih), but found this unsatisfying. He returned to England in 1982 to be with his family and to work more on his art. The artist describes having no money and going to the job centre in Hackney. The only vacancy was for a poorly paid sausage packer. He tried to apply, but was turned down on the grounds of being overqualified, too old (he was 52 at the time) and lacking experience of sausage packing. He is still practising from his home in Oxford and remains engaged with the world around him; his most recent works are a series of Coronavirus Mask drawings. All these memories are delivered with a light and thoughtful touch. El-Salahi doesn’t tell us what to think about his life, but spreads the pieces out before us, inviting us to see the many connections.

At Home in the World: A Memoir by Ibrahim El-Salahi is published by Skira/The Africa Institute.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.