Icelandic life has its own distinctive rhythms determined by seasonal change and by light, or its absence. The island’s otherworldly landscapes are at once timeless and subject to constant climatic change. No hour is the same in these expansive skies, no minute. So perhaps it is not a coincidence that from the outset, Iceland’s largest independent art festival has focused on explorations of the concept of time, often in relation to the natural world. This year’s edition of Sequences, a biennial event now in its 12th edition, was thoughtfully curated by Daría Sól Andrews, and took the theme of Pása or Pause.

Andrews regards slowness in our current cultural moment as ‘a radical gesture, a form of refusal, a counter-tempo and a necessary breath’. Her programme brings together bodies of work and performance that may be painstakingly slow in process – based on observation or research – or only reveal themselves slowly over time. Artists consciously slow down the visual perception of their work or record changes over time that are otherwise imperceptible. There is also what may be called deep time. Olfactory memory is a key component of the Fischersund Collective’s sensory installation at the artist-run venue Kling & Bang. Decay posits decomposition as transformation through sight, sound and touch as well as smell, but it is the scents – rank and otherwise – that instantly propel the sniffer back to a place in their past.

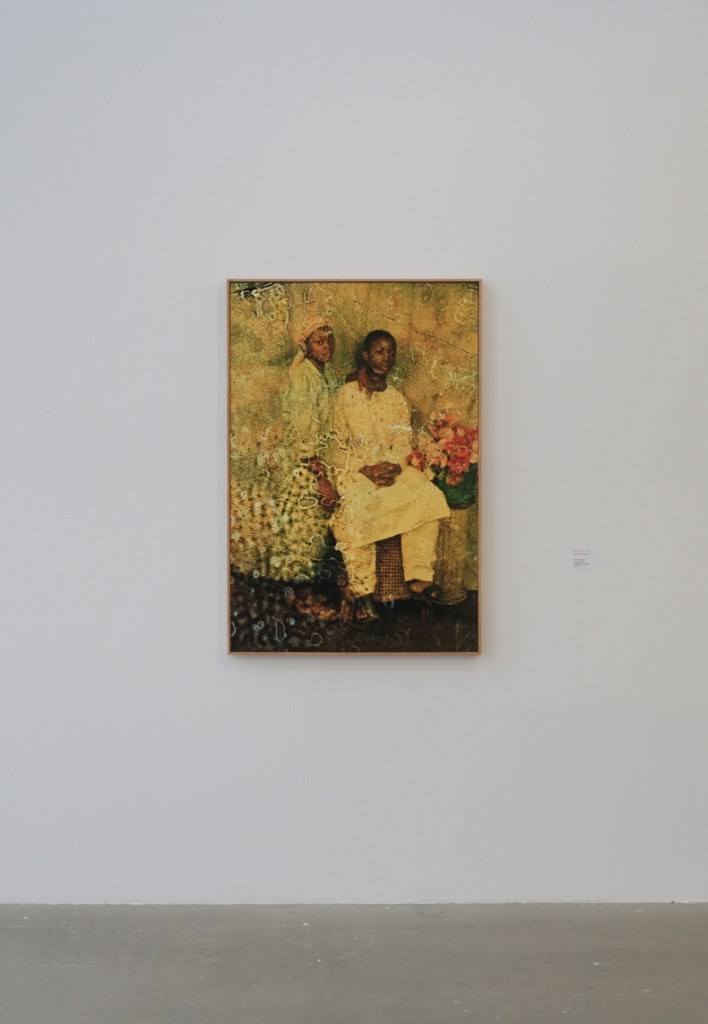

Even deeper memories, individual and collective, are considered in Aftertime at another artist-run space, the Living Art Museum. Time here is politicised, and negotiated through histories of violence, colonisation, slavery or systemic neglect. In her elegantly conceptual black and gold Land Back Now, Sasha Huber uses Morse code – a lingua franca based on touch and rhythm – to spell out in sculptural dots and dashes demands for the rights of Indigenous peoples. Also on display are the poetical and strangely painterly studio photographs salvaged over many years by the Lagos Studio Archives, their surfaces ravaged by neglect, chemical decay and mould in the West African climate. The vestigial presences surviving amid the bloom and encrustations in Archive of Becoming (2015–) are testimony to the fragility of life and its memorialisation.

Timescales where change in the natural world is imperceptible to the human eye are explored in ‘Sediment and Signal’ at the Nordic House. Ragna Róbertsdóttir works with elemental materials. Mindscape, ‘slow clocks’ where sea salt or black lava salt is mixed with water and left to crystallize, eerily evoke both the smallness of the rockpool and the vastness of the cosmos. Rhoda Ting and Mikkel Bojesen are also interested in the meeting of art and science, growing and studying living organisms such as the fungi installed here in Rhizome and interpretingthe millennia-old sediment drilled four kilometres under the ocean floorin Deep Time. ‘We are interested in what continues to evolve, survive and adapt, and what we can learn from them,’ Bojesen says.

Bryndís Snæbjörnsdóttir and Mark Wilson similarly combine fieldwork, archival research and interdisciplinary collaboration to explore human-non-human relationships, and species displacement and extinction. The video and sound pieces Time and Tide and Time and Again present dripping glaciers and narratives of man’s encounters with the polar bear, in folklore and in documented incidents. Matrix (Svalbard), a hand-blown glass recreation in reduced scale of an excavated snow den, is a chilling intimation of the vulnerability of nature in the Anthropocene. WAUHAUS invites us to reflect on an entirely man-made landscape above a landfill site and what lies beneath it – degrading or not – in the video piece Some Unexpected Remains.

Walking around Reykjavík’s exhibition venues is a reminder of how many world-class artists have emerged from this small country of some 360,000 souls. We pass the studios of Olafur Eliasson and Ragnar Kjartansson, the latter showing the durational performance film Santa Barbara. This homage to the cultural influence of the first American TV soap to show in Russia after the end of the Soviet Union, is, as director Ása Helga Hjörleifsdóttir tells us, strangely opportune at a time when the United States increasingly resembles Russia.

A collaboration between the National Gallery of Iceland and Reykjavík Art Museum presents the most comprehensive exhibition to date of the pioneering and magisterial video and new media artist Steina (b. 1940). That the artist has long been at the forefront of new technologies is made clear by her mesmerising and immersive six-channel video installation Mynd (2000), which combines Chinese landscapes and Icelandic frozen emerald oceans, horizontal and vertical channels. She used ‘time warp’ and ‘slit-scan’ processing tools to capture multiple moments in a single frame.

Asked why Iceland punches above its weight in the creative arts, Adda Valdimarsdóttir, Reykjavík’s director of culture, replied: ‘Everything begins with education. There has always been good infrastructure here.’ Exhibition and studio spaces are subsidised, and artist salaries awarded, but there are also grants to study overseas. ‘We need to be global and local,’ Valdimarsdóttir insists. Steina, for one, left in 1959 to study violin in Prague, where she met her future collaborator, Woody Vasulka. She still considers herself first and foremost a musician. Iceland’s creative culture is collaborative and often multidisciplinary – Ásta Fanney Sigurðardóttir, for instance, who will represent Iceland at the 2026 Venice Biennale, weaves various media with poetry.

Mischief also abounds. The almost contemporaneous State of the Art music festival offered chamber music in the Reykjavík Air Rescue Team’s garage and a performance of Mort Garson’s Plantasia in a greenhouse, while putting the rock into baroque with Vivaldi in a nightclub – bass, strobes, shots, wigs et al. The arts in Iceland are nothing if not unexpected.

Sequences took place at various venues in Reykjavík from 10–20 October. ‘Steina: Playback’ is at the National Gallery of Iceland and the Reykjavík Art Museum until 11 January 2026. To find out more about visiting Iceland, visit Inspired by Iceland.