From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

According to Pliny the Elder, at the beginning of art there was competition. In Chapter 36 of his Naturalis Historia he describes how Zeuxis, the greatest painter of the 5th century BC, was challenged by another artist, Parrhasius, to see who could create the most convincing trompe l’oeil. Zeuxis painted a bunch of grapes with such fidelity that birds flew down from the sky to peck at them. Confident of victory he demanded that Parrhasius draw back the curtain that hid his own submission to reveal what he had made. It was, however, the curtain itself that was painted and Zeuxis was forced to admit that he had been bested: while he had fooled the birds, Parrhasius had fooled him.

The anecdote remained popular among both artists and connoisseurs and in 1455, the scholar Lorenzo Valla codified its message: ‘It was designed by nature that nothing can progress and grow that has not been built, fashioned and worked by more than one – especially if these compete with one another for fame and praise.’ According to Valla, it was the creed of imitari, emulari, superare – ‘imitate, emulate, surpass’ – that drove art forwards.

This trio of loaded words provides the theme of ‘Idols and Rivals’, a wide-ranging and thought-provoking exhibition currently running at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Through 114 works from antiquity to the late 18th century – half of which are loans, the others from the museum’s spectacular holdings – it looks at some of the artists who took on, intentionally or otherwise, Valla’s invocation. It is a thematically rich exhibition of which every strand could be spun off into a fully-fledged show of its own.

The works are shown in pairs or small clusters and stand for any number of other examples across art. There is, for example, a pair of works that treat the mythological artistic competition between Apollo and Marsyas, when the satyr challenged the god to a musical contest, with fatal consequences. A krater by the Suessula Painter of the second half of the 5th century BC from the British Museum shows with extraordinary delicacy Marsyas playing the flute, while Luca Giordano depicts the brutal flaying of the satyr that followed. In his image of shrieking pain and horror (c. 1695), Giordano was himself emulating earlier works on the theme by Jusepe de Ribera.

The Renaissance itself is traditionally held to have started with the competition, in around 1401, for the Baptistery doors in Florence. The entries by the two finalists, Filippo Brunelleschi and the winner Lorenzo Ghiberti are shown in the exhibition by casts. Their sparring later turned into enmity when Brunelleschi humiliated his rival over his inability to finish the dome of the Duomo.

Personal dislike famously gave an edge to the relationship between Michelangelo and Leonardo – with the former publicly sneering at Leonardo’s failure to cast a huge equestrian statue of Francesco Sforza. Their private competition was made inescapable when both were commissioned to paint large scenes for Hall of the Five Hundred in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Neither work was finished but their cartoons proved hugely influential to subsequent artists. When they were exhibited side by side Benvenuto Cellini described them as the ‘school of the world’.

Ganymede (1611–12), Peter Paul Rubens. Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna

The exhibition includes possibly the best of the copies of Michelangelo’s design for The Battle of Cascina, made in c. 1542 by Bastiano da Sangallo and now at Holkham Hall, alongside Rubens’ painted version of the central scene of Leonardo’s The Battle of Anghiari, the Battle of the Standard (c. 1605). Michelangelo, in particular, proved irresistible to subsequent artists. Rubens is also represented here by his superb 1575–80 rendition of The Rape of Ganymede, inspired by the drawing Michelangelo gifted to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. Other artists of note who took on Michelangelo include Annibale Carracci, whose haunting small oil on copper of the Pietà (c. 1603) is a homage to the celebrated Vatican sculpture (itself marked by competitiveness: Michelangelo signed it, the only sculpture he did, when he heard it being claimed as a work by a rival, Cristoforo Solari).

Ganymede (1575–80), copy after Michelangelo. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo: © KHM-Museumsverband

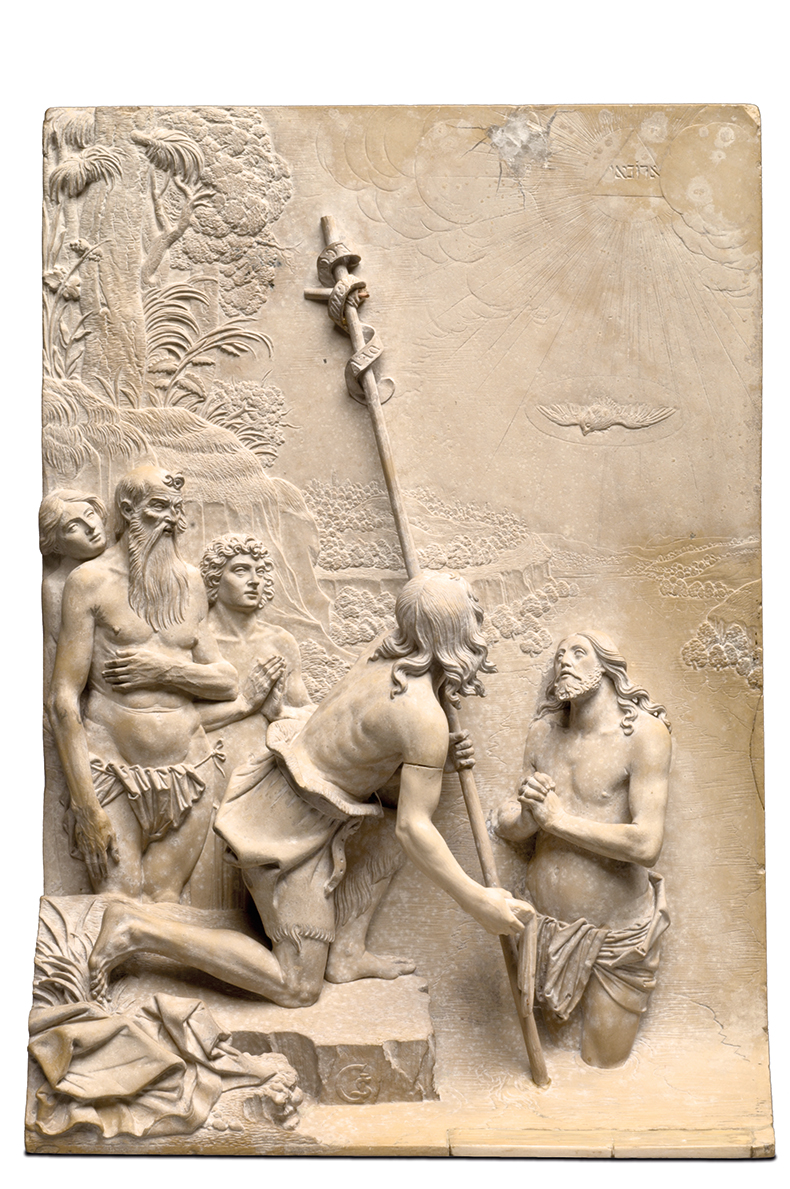

Both Michelangelo and Leonardo were key figures in the contemporary debates about the relative merits of the individual arts and a miraculous small room presents the paragone through a breath-taking selection of works. Giorgione’s Laura (1506), an imagining of Petrarch’s muse, shows painting and poetry in symbiosis; Giovanni Bellini’s Young Woman at her Toilet (1515) uses a mirror to reveal a figure from behind as in sculpture; Andrea Mantegna’s Abraham Sacrificing Isaac (1490–95) is a carved relief in paint; while the landscape background of Georg Schweigger’s The Baptism of Christ (c. 1645), a bravura work of impossibly delicate carving from the museum’s Kunstkammer, shows how a limestone relief could in its turn ape painting.

Abraham Sacrificing Isaac (1490–95), Andrea Mantegna. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Photos: © KHM-Museumsverband

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1645), Georg Schweigger. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna Photos: © KHM-Museumsverband

Similar thoughtfulness is evident too in the pairing of Titian with Tintoretto, the pupil he disliked, who were both commissioned for portraits by the Strada and Venier families. It is there in the plans which show the effacing of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s designs for the Chapel of the Magi in the Palazzo Ferranti when his great rival Francesco Borromini took over the project in 1646, and also in the fruits of the creative partnership between Rubens and Anthony Van Dyck . The essential truth expressed by Valla remained remarkably pertinent down the centuries, although the exhibition’s cut-off point in the 18th century means there is no room to take it through to such later pairings as Ingres and Delacroix, Van Gogh and Gauguin or Matisse and Picasso.

Instead, the show finishes with two Prix de Rome entries from 1771 depicting Minerva Fighting Mars, one by Jacques-Louis David and the other by the winner, Joseph-Benoît Suvée. David never forgave the victor and during the French Revolution’s reign of terror, denounced Suvée and had him imprisoned, putting his life in peril. While this clever exhibition, curated by Gudrun Swoboda and studded with a number of exceptional works, demonstrates vividly how ‘imitate, emulate, surpass’ pushed some artists to new levels of creativity, it also shows how others were led into very dark places.

‘Idols and Rivals: Artists in Competition’ is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until 8 January 2023.

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.