Munich is an apt location for an exhibition of work by Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945). The city hosted a show of 25 of his paintings in 1912–13; later, on the cusp of the Second World War, the Spanish Ambassador to Germany, on direct orders from General Franco, gave three works by the Basque-born painter to Hitler in Munich. This dubious honour did the artist’s posthumous reputation no favours. The current exhibition is the first international retrospective for a figure who was widely considered to be Spain’s greatest living artist before Picasso came along. Until then, his only real competition was Joaquín Sorolla, the Valencian-born master of light – another painter who benefited from the American interest in Spain.

Across nine rooms containing more than 70 paintings, ‘The Myth of Spain’ does a remarkable job in presenting the work of a self-taught artist who on paper had stronger credentials as a bullfighter than as a painter. The scenes of public life he created as a young man in Paris capture the beginnings of his lifelong fascination with prostitutes from different societies and epochs. In the Manet-esque Opposite the Moulin Rouge (1890), completed the year after the cabaret first opened, a young woman who appears to be a prostitute sits alone at a café table, her face concealed to the viewer but the blue plumage of her attire attracting attention. The French, in the age of Bizet’s Carmen (1875), were fascinated by the archaic otherness of Spanish customs; Zuloaga reversed the gaze, documenting the isolation and commercialisation of modern life in Paris. Although he was inspired by the Louvre and personal interactions with Gauguin, Degas and Van Gogh, modernity held limited appeal for Zuloaga. He turned his back on Montmartre and soon returned to his homeland. In later portraits of female relatives whose make-up resembles that of street workers he appears to mock their aping of cosmopolitan sophistication.

The Short Doña Mercedes (1899), Ignacio Zuloaga. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © bpk/RMN – Grand

Palais/Hervé Lewandowski

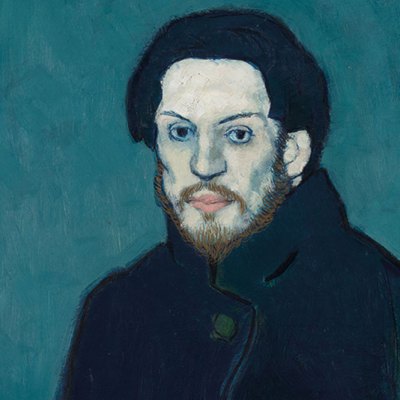

Zuloaga’s work is often as dark as Sorolla’s is light. Raised amid the rolling hills of Basque country, where the rain is as constant as the sun on Sorolla’s native Mediterranean coast, he created paintings whose hues bear testament to his darker view of Spain and its people, customs and art. In the room in Munich that brings together works inspired by Spanish Masters, my eyes were drawn to The Short Doña Mercedes (1899), in which the Doña holds a cylindrical glass bowl. In a clear nod to Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), the artist’s reflection is included in the composition. A baroque fascination with the interplay between reality and artifice recurs throughout the exhibition. Bleeding Christ (1911), a representation of a processional display with a polychrome sculpture typical of Spanish Easter parades could, at first glance, be mistaken for a depiction of the original Crucifixion. Zuloaga’s tendency to imbue realist scenes with non-realist features is evident in the vibrant greens in many of his landscape paintings – irrespective of local climate. The discrepancies of this signature style, particularly marked in his depictions of the arid central plains of Castile, reveal the imprint not only of his upbringing in a rainy, verdant region of Spain, but also of El Greco’s influence.

Bleeding Christ (1911), Ignacio Zuloaga. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

It seems fitting that the exhibition’s promotional poster features a taurine image, Half-Length Portrait of a Picador (1910). Zuloaga was a bullfighting aficionado who remained attuned to the cruelty of what is often referred to as Spain’s ‘national fiesta’. The Kunsthalle’s largest room is dedicated to paintings from a period when Zuloaga was living in gypsy communities and training as a bullfighter in a small town outside Seville. Columbus’s famous departure from the Andalusian city had resulted in the world’s first transatlantic empire, the gradual decline of which culminated in Spain’s loss of its last non-African colonies in the Spanish-American War of 1898. Zuloaga’s participation in debates among the so-called Generation of 98, a group of intellectuals and writers who came of age in an atmosphere of national decline and catastrophe, is foregrounded in the later part of the show, where scenes of Castile belong to literary and visual tropes about the soul of Spain. Alluding to Cervantes’s hapless Don Quixote, The Victim of the Fiesta (1910) portrays an unusually emaciated ageing picador (a horseback assistant to the matador) riding away from yet another provincial bullring on a bloodied nag. Man and beast are rendered equally pitiful.

The Victim of the Fiesta (1910), Ignacio Zuloaga. Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao. Photo: © Arte Ederren Bilboko Museoa –

Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

On the one hand, Zuloaga’s paintings suggest no obvious solutions for a cruel archaic country in seemingly perpetual decline. Conversely, he sought to dignify the Castilian landscape by adopting a tradition from Italian portraiture that framed eminent figures against iconic backdrops. The earliest example of this tendency is Portrait of Enrique Larreta (1912): the titular Argentinian writer and art collector, who, like Zuloaga, engaged with the Generation of 98, is positioned against the backdrop of the medieval walls of Ávila. Parallels can be drawn between Zuloaga’s rejection of the European avant-garde for the symbols and sites of an eternal Spain and Franco’s quixotic attempts to resuscitate the values and victories of the country’s imperial past. Still, the nuance of many of the other paintings on display point to an artist invested in questioning, not just perpetuating, the myths and mythologies surrounding his homeland. Such ambivalence is not exactly the stock-in-trade of many totalitarian regimes.

Portrait of Enrique Larreta (1912), Ignacio Zuloaga. Colección del Museo de arte español Enrique Larreta de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Photo: Eduardo Saperas

‘The Myth of Spain: Ignacio Zuloaga (1870–1945)’ is at the Kunsthalle München until 4 February; then at the Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg from 17 February until 26 May.