Imran Qureshi (b. 1972) is perhaps the most prominent artist to have contributed to the revival of miniature painting in Pakistan. While the techniques of the discipline continue to inform his work, in recent years he has increasingly turned to site-specific installations, such as the Roof Garden Commission at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013, or the landscape intervention at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto that forms part of the new institution’s inaugural show. His first major UK exhibition opens at Ikon in Birmingham later this month.

How did miniature painting become such a central aspect of your work?

I didn’t know anything about miniature painting when I started out – I’d only read an article about it in one of the Urdu newspapers before going to the National College of Arts in Lahore. And when I got there and discovered there was a department dedicated to it, I thought it needed too much patience – I was very into socialising and the theatre then – and that maybe it wasn’t for me. But I found I enjoyed it and was able to sit for hours and hours while painting a miniature. My teacher, Bashir Ahmed, encouraged me, as did my fellow artists, even when I said I didn’t have the right temperament. Eventually I realised it was something I could only learn there – it was the only department offering miniature painting in the world.

What was the status of the discipline back then?

There were only a few students doing miniature painting at the time – two or three students in the whole fine art department. But I started taking it as a revival began and lots of people became interested in the technique. Shahzia Sikander had just done her first pieces, which meant that lots of people joined the department. I’m now a professor in the same department – I’ve been teaching miniature painting since 1994 – and in the third year there are 25 students taking miniature painting.

Does that mean teaching young artists to be part of a long tradition, or encouraging them to expand upon what’s possible in the medium?

First we try to make the students master the technique, and understand it by copying a certain number of traditional paintings. Then slowly they’re asked to introduce what they’ve learnt into their own work. I think miniature painters are the most experimental artists right now in Pakistan. They’re doing installations, they’re doing videos, they’re working with textiles – and I think that’s all down to their training.

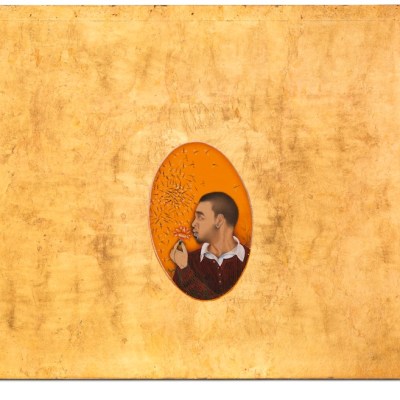

‘Opening Word of This New Scripture’, 2013, Imran Qureshi. © Imran Qureshi, Courtesy Corvi-Mora and Ikon

What, for you, are the most exciting developments that you’ve made in miniature painting?

When I started there was a conception that it was a traditional discipline that was mainly about repeating historical paintings, and that there was no margin for creativity. I took that as a challenge, and kept asking myself what contemporary miniature painting could be about. At first, I juxtaposed traditional elements of miniatures into a new format, then I started painting modern figures using the miniature technique. Eventually I realised it’s more about the essence of miniature painting, even when I’m working on large installations – if I’m drawing leaves, for example, it’s connected to the way of painting foliage in miniature. It’s about care for the line, and precision, about the specific type of brushstroke and the rhythm – which I love when I’m painting millions of leaves.

You seem to be interested in freer mark-making too?

Yes. As students we were doing lots of things around our paintings while we were making miniatures: checking our colour palette and tools at the edge of the paper, trying out different kinds of lines while making the borders, even tracing figures then hiding them behind a thick layer of paint. Then we were asked to cover those things with mats and frames. I’ve always been more interested in the process of painting than the finished product, so I wanted to incorporate those abstract marks into my work. I wanted to paint the process of miniature painting.

How important is the forthcoming exhibition at Ikon to you?

I’m very excited. Last year, I had a travelling show that went from Berlin to MACRO in Rome, and on to the Salsali Private Museum in Dubai. But here I’m showing a lot of new work, including videos: people will see a greater diversity in this exhibition. Of course, there’s a huge Pakistani community in Birmingham. I hope they connect with the work strongly, with its political content – and not just because I’m Pakistani, but because of what they’ll see in the work itself. I think that people should use their own perception in front of it – I shouldn’t guide them and say, this is the start and this is the end. When the art leaves the studio it’s open to anyone; anyone can say what they like about it or read it how they want to. I don’t want to work like a journalist and illustrate

a political situation.

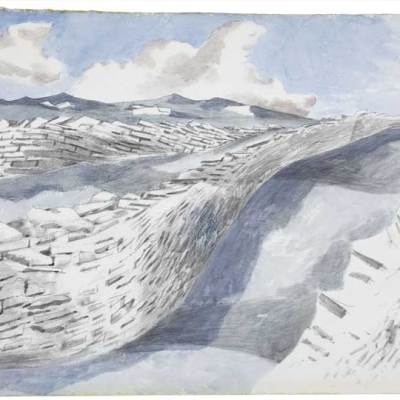

Installation view of ‘And They Still Seek the Traces of Blood’ (2013) by Imran Qureshi (b. 1972), at the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin (18 April–4 August 2013). © Imran Qureshi, courtesy Corvi-Mora and Ikon

How has your growing international profile over the last few years affected your work?

I’m quite free now in terms of proposing ideas and seeing them executed, which is a new thing for me. I feel I can be more adventurous, and the scale of my work has changed. I first made the mountain of crumpled paper drawings, And They Still Seek the Traces of Blood in Lahore last year, but now I’m thinking about it on a totally different scale. It’s taken me 20 years to get to this place. The dangerous thing right now is that there are lots of good young artists, and when they see other people’s success, their goal becomes to achieve it in a few months or a year. You have to be committed to your own art, rather than to the idea of the global art scene.

‘Imran Qureshi: Deutsche Bank’s “Artist of the Year”’ is at Ikon from 19 November–25 January 2015.