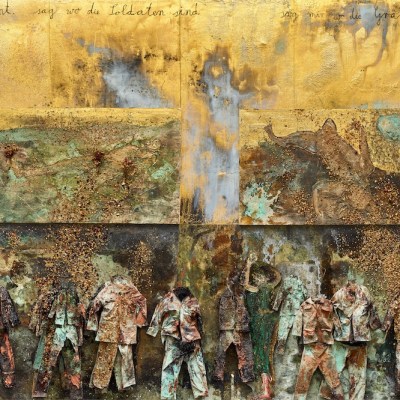

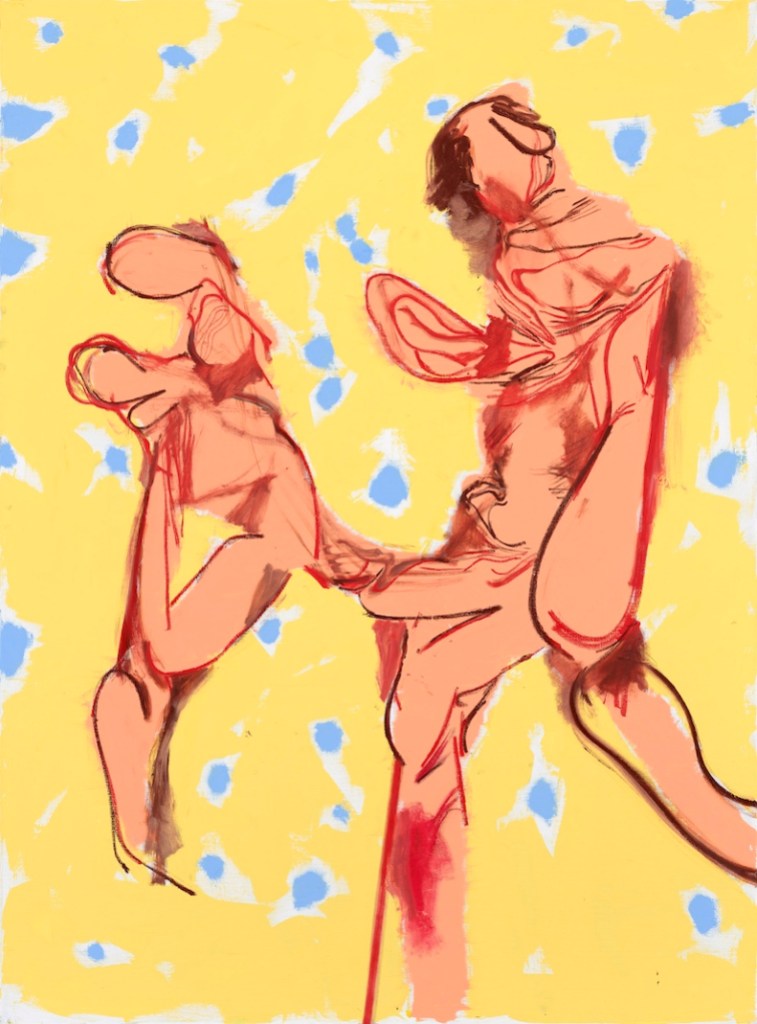

In the 1990s, early in his career, the German painter Daniel Richter (b. 1962) worked as an assistant to Albert Oehlen, whose maximalist, expressionistic approach to abstract painting had a formative influence on the younger artist. Richter’s work has been through several stylistic shifts, from abstraction to figuration; in his recent work he has focused intently on depicting human figures, often in distorted ways. The artist has wide interests – in the ’90s he designed posters and record sleeves for bands, and he now runs a publishing house, PAMPAM, with his wife, the Austrian photographer Hanna Putz-Richter. His latest body of work – a group of striking, brightly coloured paintings that meditate on the limitations of the human form – is on display at Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg, from 25 July–27 September.

Where is your studio?

My studio is in Berlin, in an area called Schöneberg – Christopher Isherwood lived just two houses away 100 years ago. It’s just a classic kind of craftman’s workshop. I think it was part of the old Metropol theatre.

How would you describe the atmosphere in your studio?

Work-related. There are lots of paintings, records and books, and that’s it. It’s actually not a very beautiful place. It’s also, sadly, not super big. I have to use the elevator to get paintings in and out, so I can’t paint anything larger than three metres across. It’s not like one of those lofts you might see in Architectural Digest.

Is there anything else you don’t like about your studio?

Berlin. There are parts of it I enjoy, but I think it’s a really good city when you are young, when you like drugs and sex and clubbing, and you can have a relatively cheap life compared with many other cities in Europe. I stay at home most of the time and read and listen to music. Maybe I just don’t really know what Berlin is about, because I rarely go out. It’s a city that was always a promise, and that promise wasn’t kept. I’m from a small village north of Hamburg, and when I was 16 I moved to Hamburg itself, so I consider myself a Hamburgian.

What does your studio routine look like?

I mostly work in bursts of six or eight months. Most of the time I stay in the studio. Working includes brooding and staring at the wall and self-doubt and reading and thinking, and then taking the brush or the knife and then working, and then staring at the wall for another 20 hours. And then I do the same thing again. I don’t really have a fixed routine, where I start at a certain time or anything. After the show has finished or the work is done, I usually get grumpy and depressed, and I look at the work, and then I think, ah, okay, I achieved something. Then, after maybe half a year or a year, I start to feel unhappy with the work again, and I think – okay, there’s more in it. So I start working again.

I think there’s a discrepancy between the drama that you experience while you’re working and the reception of the work. Often I present a body of work and I feel like I have made quite big, formalistic changes; but to others, it’s just another painting of a man or a woman; another painting by Daniel Richter. I wish it was different – I wish people would say, ‘Wow, that’s another astonishing step!’

Do you have many visitors to your studio?

I’m married and I have a kid, so they come by now and then. Sometimes my friends come by – every two months or so. They try to cheer me up, or flatter me. But on the whole I don’t have many visitors.

Do you listen to anything while you work?

I listen to music – I think music, as well as literature, is the biggest comfort or joy that mankind can offer. I think music is much more fun than painting, and much more accessible. I love reggae, especially from the late ’60s to the early ’80s; I listen to certain kinds of techno too. And I love early 20th-century classical music: Shostakovich, Bartok, Schoenberg, that kind of stuff.

What is the most unusual object in your studio?

I think it would be a gogotte, which is a stone that has been shaped by changes in tectonics over thousands of years. They’ve only ever been found in very specific areas of France, in places where castles have been built, and there are a limited number of them because it’s not like new ones keep being found. They look like modern sculptures – a mix of Tony Cragg, Giacometti and Jean Arp. But they’re actually stones. Mine is about a metre across.

I also have a very, very good sound system, and it’s slightly unusual because it’s built by a woman: there are actually fewer women in the world of sound system engineering than there are in Formula 1. It’s a completely male-dominated, nerdy world.

What is your most well-thumbed book?

The one I probably return to most is Moby-Dick. Recently I read a very interesting book by Benny Morris called 1948, which is about the foundation of Israel. I also read a lot of German books, like Europe Central by William Vollmann, though many of them haven’t been translated into English. And to my surprise, I really enjoyed Infinite Jest. It’s a book I would like to read again.

As told to Michael Delgado.

‘Daniel Richter: Mit elben Birnen’ is at Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg Villa Kast, from 25 July–27 September.