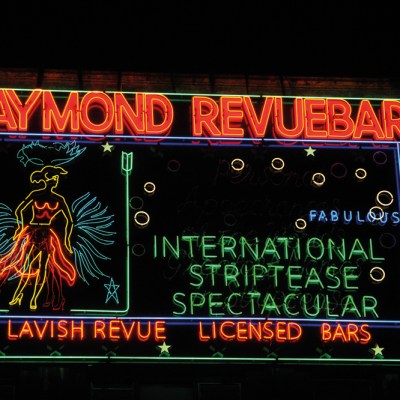

In his films, installations, photographs and performances, the Scottish artist Douglas Gordon investigates collective memory, language and psychological states. He often appropriates material from other artists and filmmakers – as well as his own archives – to create multilayered works that distort time and space. ‘I’m interested in the fine line between my intentions and the perceptions of others; that moment when someone encounters something and realises that there is more to it than meets the eye,’ he has said of his practice. ‘Neon Ark’, Gordon’s solo exhibition at Gagosian gallery in London (until 14 January), is dedicated to the text-based works he has been making since the 1990s and includes a live workshop in which artisans can be seen fabricating neon works by bending glass tubes on a naked flame before adding noble gases, molecules of which emit light when activated by electric currents. To coincide with the exhibition, CIRCA is also presenting a work by Gordon on the large screen in Piccadilly Circus (until 31 December) that responds to the long history of neon lights in Soho.

Where is your studio?

My studio is in Berlin.

How would you describe its atmosphere?

Unique. I always work in the dark because I work a lot with photographs, films, smoke, fire. If you were to break into the studio tonight you would probably run for your life. Quite a few people have. Especially the security firm who look after the place. The studio is quite big, and it’s in an L-shape. So if I happen to be at the wrong end of the L and someone comes in the other door, they can’t see that I’m there and they shit themselves. I’m somewhere in the ether.

One time, I thought that I had destroyed all fire alarms in the studio, but there was one that I hadn’t destroyed that was a silent smoke alarm. The police and the fire department turned up fully armed with guns. I think they thought there was something going on that was somewhere between witchcraft, robbery, pornography, crack and crystal meth.

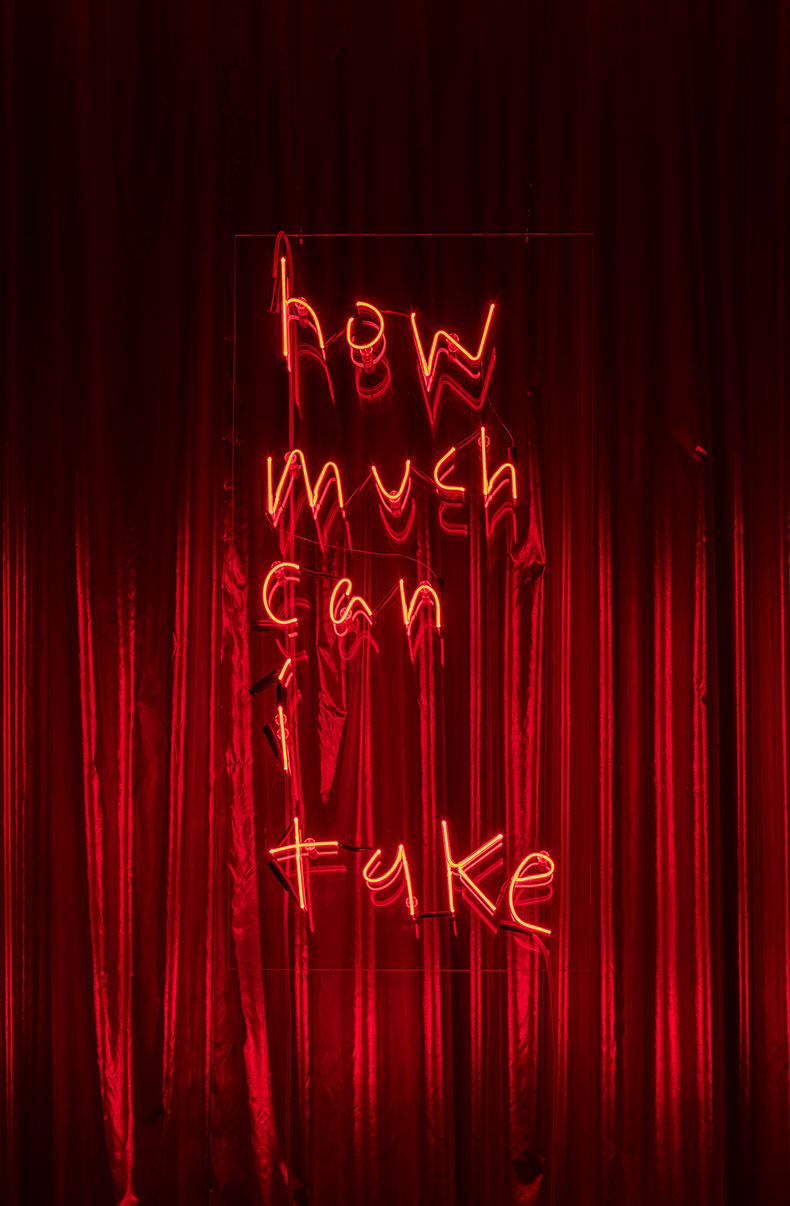

how much can I take? (2020–22), Douglas Gordon. Photo: Lucy Dawkins; courtesy the artist and Gagosian

When is your favourite time of day to be in the studio?

During Covid, lockdown, shut-up, whatever you want to call it, you couldn’t go to the Berghain club because all of the nightclubs were shut. It meant that I started to enjoy the darkness in the studio. I have a great sound system and people knew they were able to pop by.

Is there anything that frustrates you about the space?

No. I’m totally happy. You couldn’t find a place like this in Glasgow. It’s in a nice hof [courtyard], with a fantastic bookshop and a lot of artists – there are painters, sculptures, performance people. Someone came into the hof and asked, ‘Is this where the art school is?’ It has the atmosphere of the art schools that don’t tend to exist anymore – it reminds me a lot of my art school days. There’s really nothing to complain about. But maybe ask my neighbours.

Gordon in his studio in Berlin. Photo: Studio lost but found / Frederik Pedersen; © Studio lost but found / Douglas Gordon / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2022

Do you listen to anything while you work?

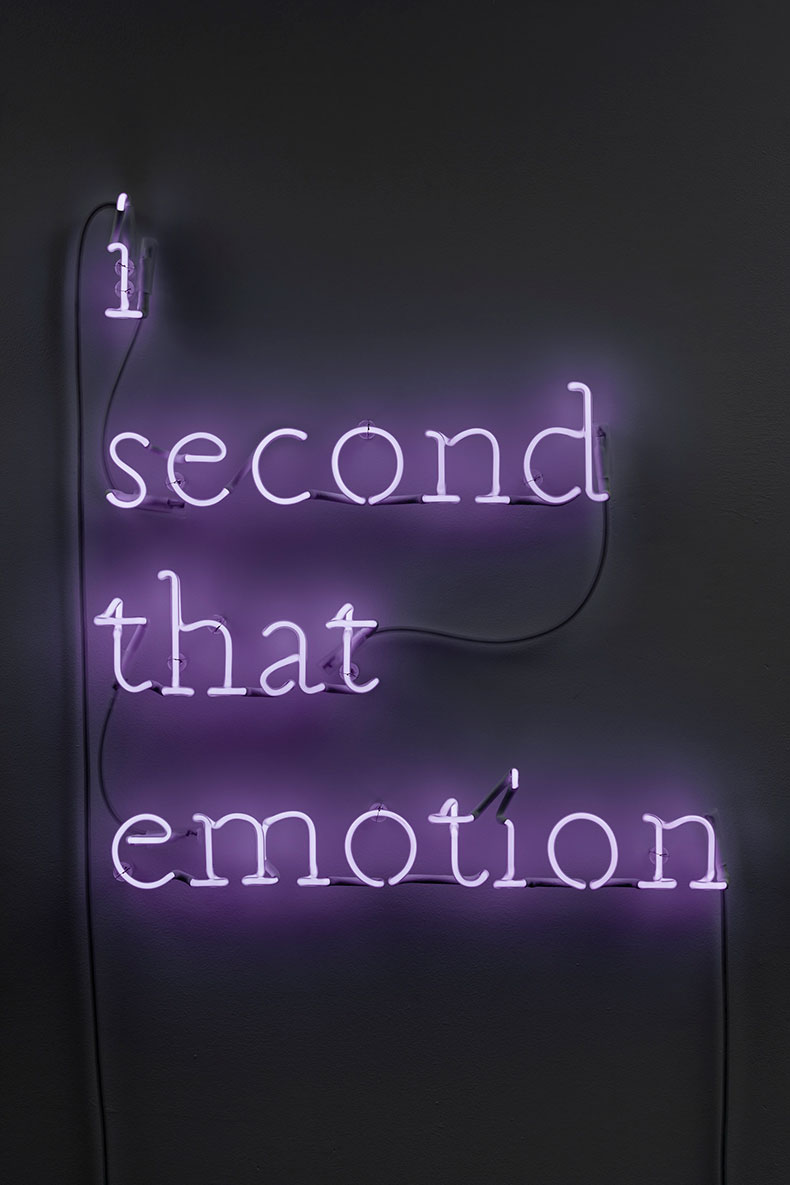

There’s never a quiet moment. The whole show at Gagosian in London is based on lyrics. I grew up in a musical family, my Dad played the bagpipes in a council house – that’s the kind of tolerance I have built up. In Glasgow, you either have to be able to kick a ball, play guitar or paint a picture, preferably all at the same time. I listen to a lot of Irish rebel music.

What’s the strangest object in there?

Who told you about the Narwhal penis bone? A friend of mine gave it to me for my 40th birthday. It’s about the size of a baguette and weighs a tonne. It stands next to my rifle, which is next to my arctic wolf.

i second that emotion (2022), Douglas Gordon. Photo: Lucy Dawkins; courtesy the artist and Gagosian; © Studio lost but found/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, Germany 2022

Who’s the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had to the studio?

The burglar who came in when I was there. He’s never come back. He got more than he bargained for – seeing a Scotsman dancing with an arctic wolf, he ran for the hills. I’m joking, everyone who comes into my studio is interesting.

‘Douglas Gordon: Neon Ark’ is at Gagosian, Davies Street, London until 14 January.