Lucy McKenzie was already exhibiting her work regularly when in 2007 she began studying at the Van der Kelen Logelain school of decorative painting in Brussels. Her paintings and installations draw on the 19th-century techniques taught at the school, with a particular emphasis on the the trompe l’oeil tradition. Work in other media includes a collaboration with Beca Lipscombe on Atelier E.B., an experimental fashion label. Currently on view at Tate Liverpool, McKenzie’s first UK retrospective brings together more than 80 works from the mid 1990s to the present day.

Where is your studio?

In the city centre of Brussels.

What do you like most about the space?

It is an old storage building that I converted, so I could add details that are practical for a painting studio. For instance, an extra-wide space in the stairwell so that large canvases can be easily moved between floors. Also, it’s invisible from the street and is a quiet sanctuary in a noisy part of town.

What frustrates you about it?

After working there for more than a decade I know what could be added or built to make things easier and nicer, but implementing those plans is always postponed because I’m too busy or lazy.

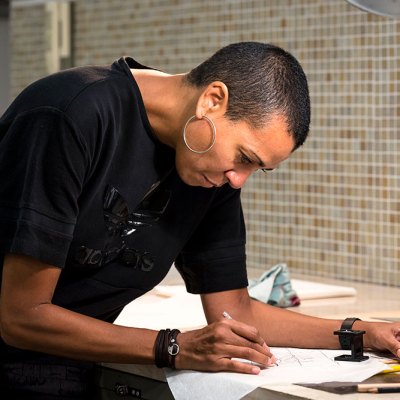

Workcoats (2010), Lucy McKenzie. Courtesy the artist; © Lucy McKenzie

Do you work alone?

I have two assistants who have worked for me regularly for almost 10 years now. They come twice a year for a month each time, and I save up a lot of different jobs for us to do together. We work like demons in those weeks.

How messy is your studio?

Not too bad. I studied decorative painting and have done a lot of large-scale painting on site, which can only be done stress-free with good planning, so I fell into good habits. And I do various different things in the studio – not just painting, but also dress-making – so it has to stay flexible and clean.

What does it smell like?

Linseed, turpentine, varnish, wax, hay-like odours from the metres of pre-primed canvas. Visitors love it.

What’s the weirdest object in there?

I don’t have any weird objects in my studio, it’s a workroom. But I do have a beautiful 24-hour clock by Tauba Auerbach, and a framed certificate from my decorative painting school.

Which artistic tool could you least do without?

My special wooden ruler for painting straight lines. It was made for me by a craftsperson to be the right length and weight.

Side Entrance (2011), Lucy McKenzie. © Tate

What’s the most well-thumbed book in your studio?

I don’t have any books, but I do have ring binders full of my recipes for different painting procedures – gilding, painting skies, shadows, wood, marble etc.

Do you cook in the studio?

My studio and home are connected, and I always cook lunch for and with anyone who is working with me there. I am grateful for any help, and this is a small way to show appreciation (and keep stamina up).

What do you listen to while you’re working?

When I look at old work, I can often hear the things I was listening to when I made them. BBC Radio 4 coverage of the 1997 general election… Wuthering Heights read by Patricia Routledge. I stopped listening to music in the studio when I realised it had a direct effect on painting wood and marble. Techno made me feel like I was having a heart attack, and everything got jittery; classical music made the lines wavey and languid. So now it’s only audiobooks, podcasts and radio.

My brain has been cauterised by a lifetime of consuming murder-pornography, and I try to tone it down when the studio assistants are around, but they are almost as bad as me. Typical working audio would be every book in the V.C. Andrews series Flowers in the Attic or Atlas Shrugged. I have a parasocial relationship with one podcaster with a beautiful voice; I’ve listened to hundreds of hours of him talking about evil. His voice makes working (which can be lonely, physically painful and relentless) bearable.

What do you usually wear while you’re working?

A white work coat, with degrees of cleanliness depending on the work.

Is anything (or anyone) banned?

No, but anyone with cat allergies is forewarned.

‘Lucy McKenzie’ is at Tate Liverpool until 13 March 2022.