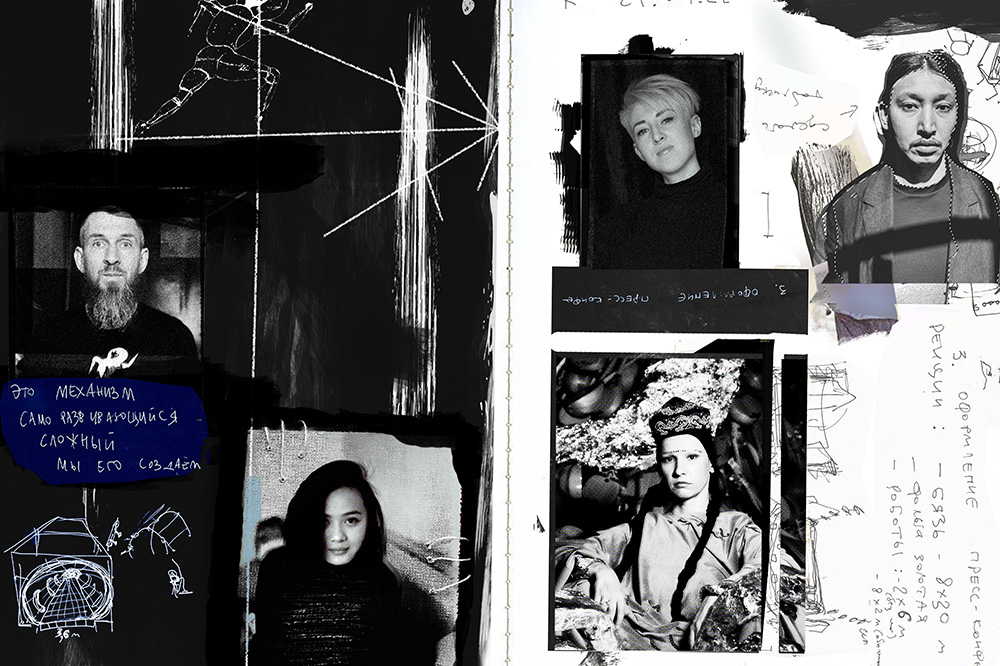

ORTA is a multidisciplinary Kazakh artist collective made up of Alexandra Morozova, Rustem Begenov, Darya Jumelya, Alexandr Bakanov and Sabina Kuangaliyeva. Their work encompasses performance, music, painting, sculpture and embroidery. Their most recent installation, LAI-PI-CHU-PLEE-LAPA, created for Kazakhstan’s first-ever national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, explores the concept of ‘New Genius’ through the work of the artist, writer and inventor Sergey Kalmykov (1891–1967). Due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, the arrival of many of the works and materials that they created in Almaty have been delayed, as the vehicles carrying them had to re-route through Georgia, requiring the artists to assemble a makeshift studio in Venice. They have said, ‘We are incredibly disappointed but compared to the greater tragedies unfolding elsewhere in the world, our own setbacks feel very minor.’ The pavilion is scheduled to be fully mounted by 17 May.

Do you have what you would consider a studio space?

No. Most of the time what we do is talk. We talk, talk, talk. When the project is beginning to crystallise, then we need space. Most of the time we talk while we walk. It’s better to talk about some distant subject. We don’t meet to discuss work, we meet and talk about some philosophy and then we can say, ‘Oh, what about that room? Let’s put an elephant there.’

For example, this project for the Biennale happened in September, though some of the materials were made in 2018 and we kept them in the warehouse – those materials were just used cardboard and we kept them for three years. When we started preparing in earnest we rented a warehouse and built the whole installation there. When we talk about genius, there are some principles – the main one is not to push or press. As an old Chinese book says, ‘You just need to do nothing and things come will come as they need to come.’

The LAI-PI-CHU-PLEE-LAPA workshop in Venice. Photo: © ORTA Collective

Where was the warehouse?

In Almaty.

How messy is your working environment?

It’s not too organised. It’s creative and chaotic. We work with different teams, metal shops or hydraulic shops or the workshop who made the robots, and we bring it all together in one place which is usually messy.

Do you have lunch together?

No. We don’t do this team-building stuff, we never do it.

What’s the most surprising object in the workshop?

Everything.

Do you pin up images of other artists’ works?

Nothing that would inspire us. You need to get the work deep inside so you forget how it influences you. Sometimes you realise later where an idea comes from, but you didn’t know it when you used it and that’s the cool thing.

Do you play music in the workshop?

Usually, no. Sometimes a technical worker, whom we love, puts something on that is fantastic and funny.

Photo: © ORTA Collective

As a lot of your work for the Biennale is currently stuck on a boat, you’ve had to transform your pavilion into an installation and a studio. How has that been?

It took some time. The space itself is very cold and quite office-like. What we usually do is take time to sing songs before we bring anything inside a space. When we bring in our things, then it comes to life. Usually, the stuff has to contradict the environment so if the space is new and nice, we bring something that is wooden, we bring trash. After about a week, this place started to become more real, more living and it became easier to work.

Is anything (or anyone) banned?

Marijuana is banned absolutely – of course it’s illegal in Kazakhstan anyway – and alcohol is banned. We don’t let ourselves bring personal things into the space. We’ve known each other for many years, but even when we talk about philosophy we keep in mind that we have a bigger goal and that’s what we work towards together.