Torkwase Dyson describes herself as a painter who works with a wide range of media, including performance, sound, sculpture and architecture, to explore Black history and the ways in which the body moves through space. Her works are typically rendered in intensely black pigment and are the result of iterative drawing and research processes. ‘I am trying to make a move with geometric abstraction within the history of visual politics, considering spatiality and negative space,’ she has said. Dyson’s work is included in the group exhibition ‘Living with Ghosts’, curated by the writer, critic, and curator Kojo Abudu at Pace Gallery in London until 5 August.

Where is your studio?

In New York. It’s in a collection of warehouse buildings. The buildings are large, but there’s a small community. There are only three of us, for example, in my building.

Do you have a specific studio routine?

It’s a new studio. I’ve only been here for about four months and it varies how often I’m there, but it helps that the building is about 30 seconds from my house. I tend to be there morning to late afternoon most days.

What do you like most about the space?

The scale of it. It’s large enough for me to organise my materials, bring in new equipment and make larger paintings and sculptures, but I have it organised so that I can make intimate works, too.

Do you work alone?

It depends on the project, but I have a studio director who has been with me since 2019 and I recently hired a sort of director of design who is helping with the larger-scale architectural projects. With the move to the new studio, I was able to grow my practice, so we’ll see where it goes.

Symbolic Geography #1 (Hypershape) (2022), Torkwase Dyson. © Torkwase Dyson

Has your studio practice changed over the years?

Absolutely – everything evolves with time. I think the older I get, the more curious I get and the more I can set up systems to satisfy that curiosity. I find that I’m revisiting things, things that I read in my twenties or thirties. Right now, for example, I’m in the process of revisiting a kind of modernism that was around between roughly the 1890s and 1920s. I’m thinking about musicians and makers around that period who were trying to negotiate what it means to create a new world. I’m specifically interested in the engineering, architectural practices and musical practices of that time – things that have a lot of structure in their making.

Do you pin up images of other artists’ work in the studio?

Not necessarily. I tend to pin up maps, images of infrastructure that I take on site, research notes. I also have images of people who inspire me. Right now, I have images of Mahalia Jackson and Frederick Douglass. I have a slew of images of projects by Elizabeth Diller, such as the Blur building and written bits of text and quotes. All of this goes onto a wall in the studio and at the centre there’s like a core, which is where my logic comes from. To the right and left of that are the projects – those change, but the centre stays pretty stable. It’s like a mind map and a calendar; it’s where important dates are noted.

Do you listen to anything while you’re working?

It depends. Sometimes I listen to books on tape. Sometimes I listen to music. If I feel tight when I’m working, or sort of non-experimental, or as if I’m getting away from my true self, I’ll listen to something like the nine principles of physics – something about space or time or experimental jazz; something that opens up my mind a bit. So, right now, I’m listening to Seven Brief Lessons on Physics by Carlo Rovelli and Alice Walker’s collected fiction.

What’s the strangest object in your studio?

There are these little black and blue beads of wax. I was trying at one point to make a drawing and have a sort of ghostlike image. So I made a drawing on a surface and then put the beads on top and air dried them, so I could use the wax in its liquid form when it becomes really transparent. It’s a curious material; its viscosity is really interesting to me.

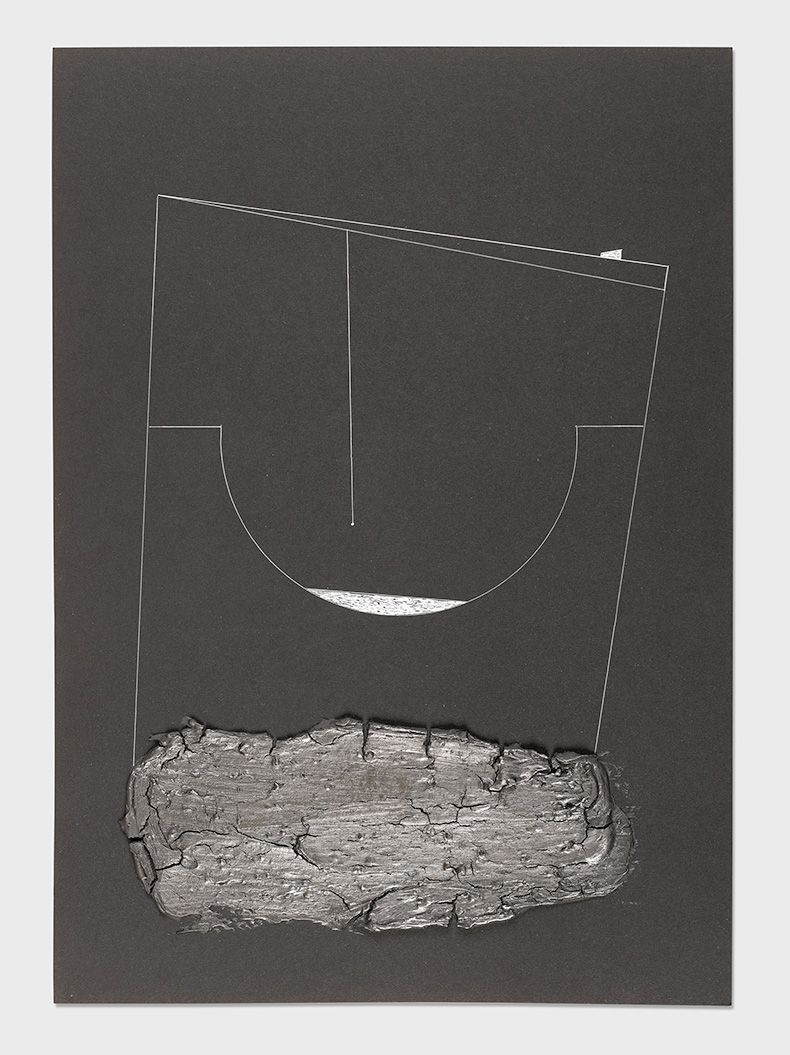

Enclosure/Encounter – Studies #4 (Hyperspace) (2022), Torkwase Dyson. © Torkwase Dyson

My brushes. I have one bucket [of brushes] that takes me from the beginning of the painting to the end. I tend to start with the larger brushes and work my way to the smaller ones. There are about eight of varying sizes and bristles. The brushes are like musical notes: each one does something very different and, over the years, I’ve collected enough to give me the sort of tone that I want.

Who’s the most interesting visitor you’ve had to the studio?

The funniest person I’ve ever had in the studio is my father. I was working on a deadline while he was in town, so I said [he should] come to the studio. He just sat there all day, watching and shaking his head because the way I make movements is very physical. I move the canvases around a lot: they’re on the floor, they’re on the wall. When I get to the point of painting, I’m normally working by myself – so nobody else was there but he was.

Was it distracting to have him there?

No because I had to focus and couldn’t tend to him. We’re both huge fans of Alice Coltrane and Johnny Hartman so I knew that if I put on some really good music, he would be OK just listening and watching.

Is anything or anyone banned from the studio?

I like a very clean floor so maybe I would ban shoes, mud or debris. We’re still finishing renovations so the floor isn’t quite where I’d like it to be at the moment, but I have studio shoes that don’t go into the outside world and sometimes I paint barefoot. My paintings often start on the floor, too, so I like to have a clean space for them.

Torkwase Dyson’s work is part of ‘Living with Ghosts’ at Pace Gallery, London, until 5 August.