Why and how do artists draw? It’s a physical and mental exercise, the creative equivalent of morning stretches or going for a run. If you’ve ever settled down to draw anything, whether for one minute or one day, you’ll know you see something more clearly by doing so than you would in a week of looking alone. Above all, drawing is a tool to develop technique, work out compositions and form and express ideas.

The ways in which artists have used drawing as a mechanism and meditation has preoccupied dealer Stephen Ongpin and art advisor Sophie Camu for the past two years, as they compiled their latest exhibition.

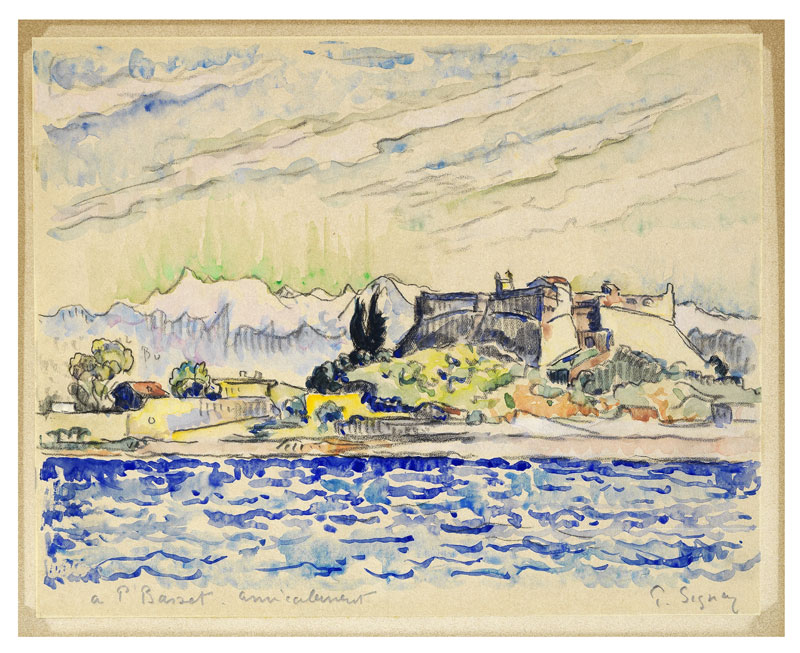

View of Calvi, Corsica (1935), Paul Signac.

‘Drawing Inspiration: Sketches and Sketchbook Pages from the 19th and 20th Century’ (17 June–28 July) was born out of Camu and Ongpin’s 2014 show devoted to the art of the pastel. The two works on paper specialists are united by their love of drilling down into one area of artistic practice and finding resonances across the centuries. For Ongpin, the thrill is in the feeling of closeness to the artist, of ‘almost looking over his shoulder as he develops his ideas on paper’.

It is not the aim of this exhibition to provide a comprehensive history of the sketch, but rather to look at the ‘transition from academic drawing to a fluid expression of ideas pioneered the by the Realists and Impressionists in the 19th century and developed over the next 150 years.’

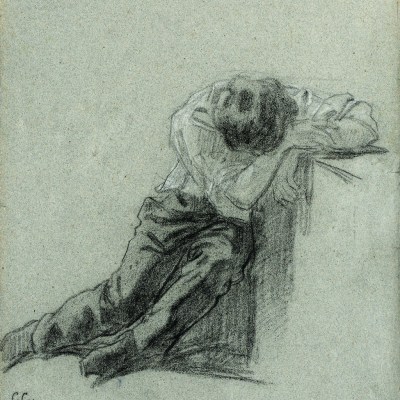

A Standing Moroccan Man (1832), Eugene Delacroix

This is a show of individual pages rather than entire sketchbooks, and British and French artists created the majority of the works (there are about 60 in total). Drawings by household names such as Picasso, Gauguin, Degas, Bonnard, Redon, Klimt and Cézanne sit alongside less familiar gems that occasionally steal the show – such as the extraordinarily naturalistic genre studies of German draughtsman Adolph von Menzel.

The display kicks of with the mid 19th-century artists Jean-François Millet and Eugène Delacroix, who freed themselves from making formal copies of the work of their forebears by drawing from life instead. Delacroix’s study of a Moroccan man, made during his trip to the country in 1832, is a particular highlight. Then the interpretation of sketching mushrooms, through the Impressionists’ loose en plein air scenes to Frank Auerbach’s gritty interpretations of modern London.

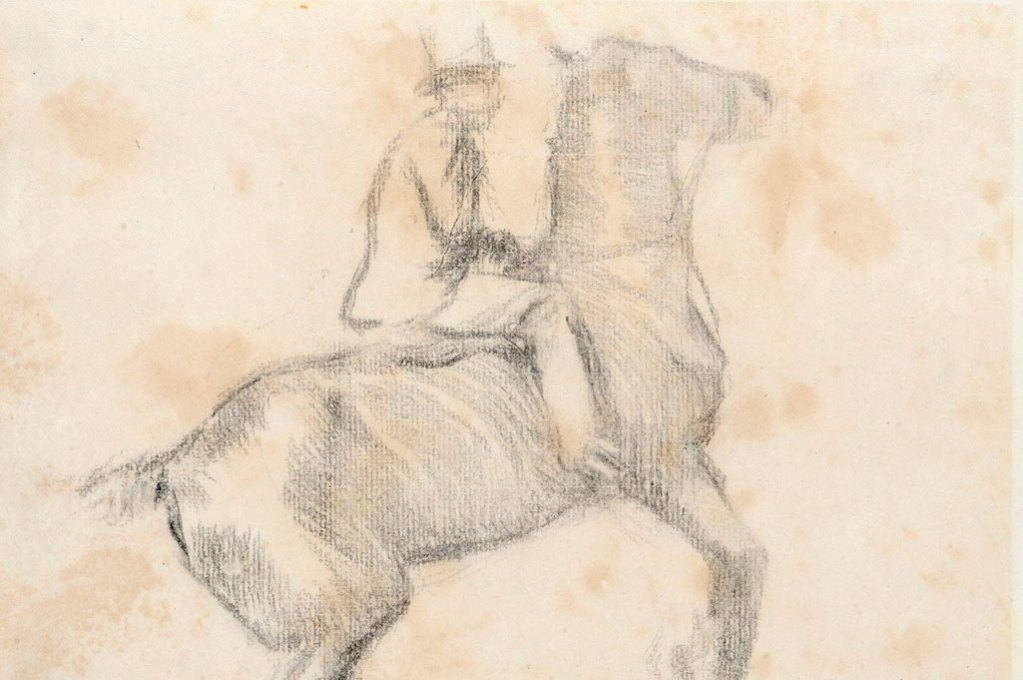

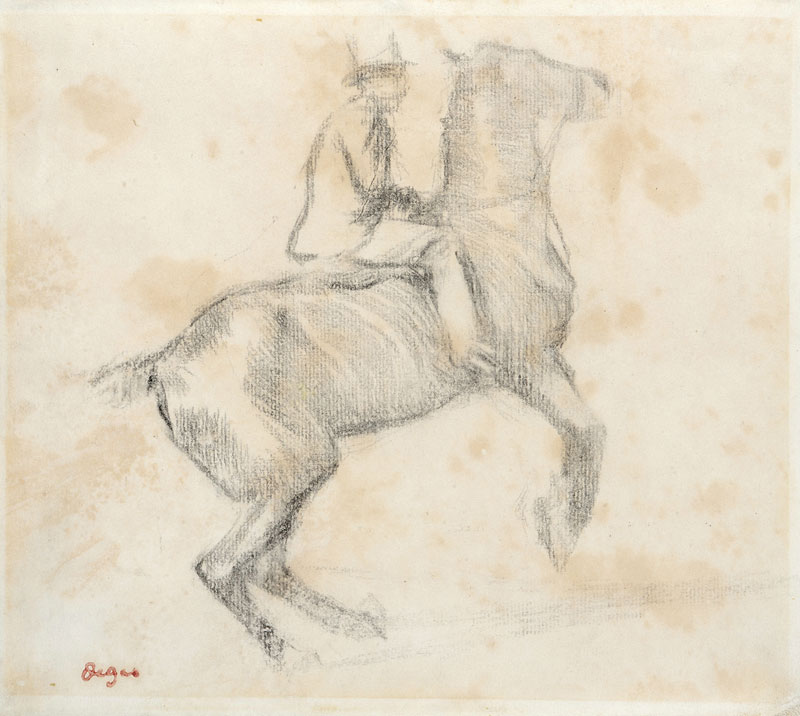

Horse and Rider (Cheval se cabrant (La courbette) (late 19th century), Edgar Degas

In most instances the exhibition includes a single representative work from each artist, but it is where Camu and Ongpin have sourced a cluster by one hand that the show is most enlightening. These groups of works illustrate how an artist’s employment of drawing can change throughout their career. Three Degas sketches are a case in point. An early study of The Head of the Virgin, after Perugino, is one of numerous drawings after past masters that Degas made in the Louvre – the sort of studies which, say Camu and Ongpin, are ‘the antithesis of what Delacroix wished to achieve through sketching from life.’ But then, an older, more spontaneous Degas records a horse rearing (Horse and Rider) and a bather (After the Bath) in swift, workmanlike compositional studies.

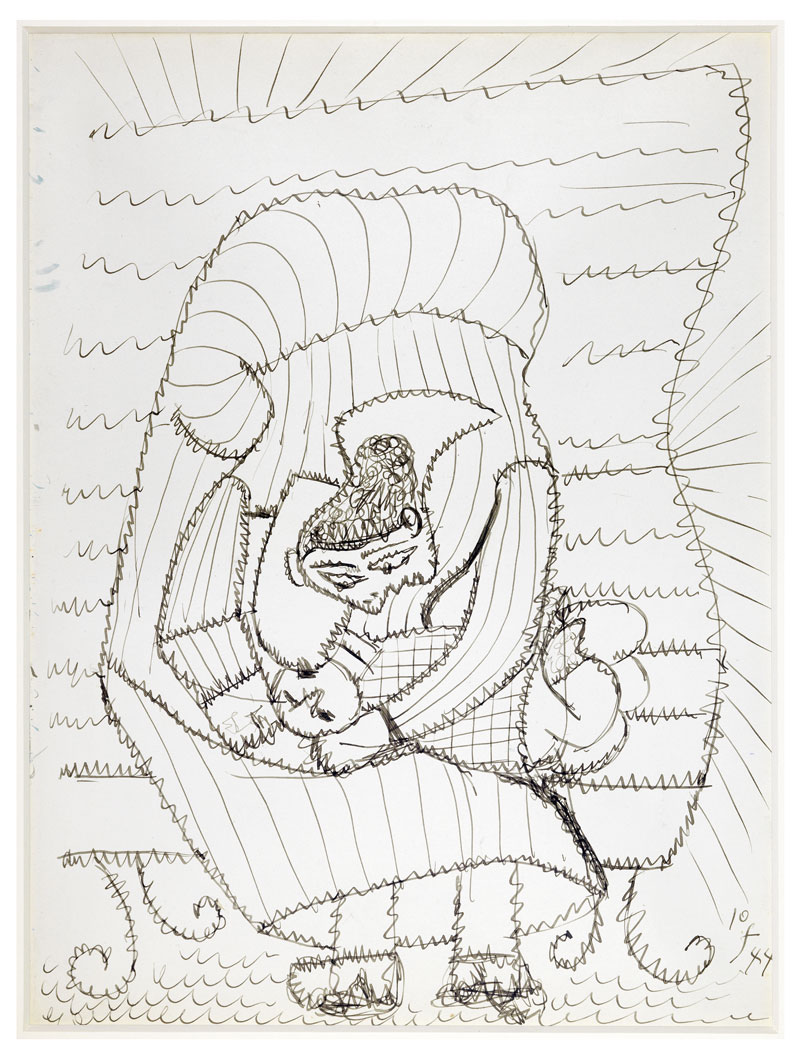

A Mother Nursing a Child (1944), Pablo Picasso. (Four sketches for a landscape composition with the Square du Vert-Galant, and another study of a mother and child to the verso).

Then there are three quite different works by Picasso, who tended to draw from memory and imagination. The works span 40 years: Seated Nude with Cat, from the height of his Rose period in 1905, is hastily recorded on a double page of a small notebook; the second, a crisp Ingresque study of his first wife Olga reclining on a divan from c. 1918, reveals how he experimented with a ‘classical’ style; the third depicts a mother nursing her child on a park bench in occupied Paris of 1944.

From portraits, to life studies to landscapes, this unaffected, thoughtful show illustrates, quite simply, the desire of artists to record the everyday, to capture light and form, with little more than a line on paper.

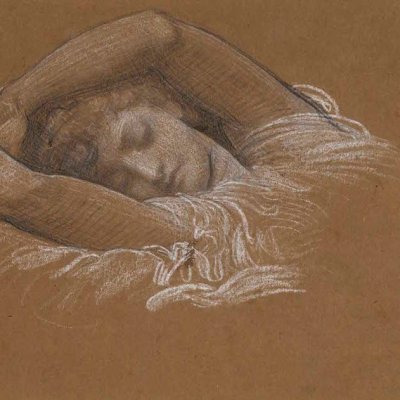

Portrait of Lady Anderson (c. 1952), Lucian Freud

‘Drawing Inspiration: Sketches and Sketchbook Pages from the 19th and 20th Century’ is at Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, London, from 17 June–28 July. Prices range from £3000 to £350,000.