Sporadic howls and thuds punctuate my conversation with Yinka Shonibare. On the ground floor of his studio – a repurposed warehouse on the eastern stretch of Regent’s Canal in London – a theatre troupe called Tangle is practising for an experimental production of Ben Jonson’s Volpone. This is the latest of Shonibare’s Guest Projects – the residency programme the artist established upon acquiring the space 11 years ago; concerned by the aggressive commercialism of today’s art world, Shonibare wanted to create ‘a space where artists can be allowed to fail – where the process of making is as important as the actual finished work’. Strains of choral jazz reach our ears, and he smiles. ‘It’s like one big playground for artists.’

The space upstairs, where Shonibare works, is more like the teachers’ lounge. We sit at a large wooden table, clear but for biscuits, grapes and tea, while behind us four studio staff tap away at computers. There are tell-tale signs that this is the province of an artist; above Shonibare’s head hangs one of his circular Fetish paintings from the late 2000s, studded with nails around its rim like a Congolese nkisi sculpture, while from one doorframe reams of vivid batik fabric – the material that has become the artist’s hallmark – spill down like a display in a haberdashery. But with its neatly stacked shelves of books, and in the centre a large square counter laden with touch-screen devices, the studio seems above all a place of well-ordered comfort – more designed for thinking and planning than for the messiness of making.

Perhaps this reflects the fact that the artist, known above all for the voluptuous sculptural tableaux he began producing in the 1990s, has shifted his focus in recent years to less tangible projects. In 2021, as the culmination of a project several years in the making, Shonibare will launch a residency programme for artists in Nigeria. Guest Artists Space will invite artists, curators and architects from all over the world to live and work in two spaces: a studio in Lagos and a barn on a 54-acre sustainable farm in the town of Ijebu, a couple of hours drive outside the city. It is to be a place of ‘cultural exchange’, where international artists can absorb the Nigerian art scene, and vice versa.

Yinka Shonibare, photographed at his studio in London in February 2020. Photo: Tereza Cervenova

When we meet in mid February, Shonibare is occupied with raising funds to establish a permanent endowment for the residency. A charity auction is planned at Phillips in London in May – the artist tells me that the number of consigned works has just passed 60, and the roster of artists involved, from Olafur Eliasson to Sonia Boyce, reads like an auctioneer’s Christmas list. Munching on his biscuits – ‘I should be eating the grapes’ – Shonibare reels them off one by one, proudly and methodically, absorbed in the immediate minutiae of a process that ultimately extends far beyond the launch of the residency next year.

‘The idea really began,’ he says, ‘with me wanting to build a contemporary art museum in Lagos.’ But after commissioning a report on art spaces in Nigeria, he realised that the crop of ‘trained curators and art historians and conservators’ needed to run a ‘sustainable institution’ of the calibre he wanted just wasn’t there. Undeterred, he has decided to grow one from grassroots. The arts scene in Nigeria is burgeoning – last month, the Yoruba prince Yemisi Shyllon opened a museum for his vast private collection of African art, and there are plans in the offing for a centre of Yoruba culture, the John K. Randle, funded by the Lagos State Government. Shonibare notes these projects with guarded approval, for he is also clear that, as of yet, there is no serious institution for international contemporary art in the country – and internationalism is at the heart both of his art and of his politics. ‘The project is connected to all of these things that we’ve been fighting against since before the Second World War. We’ve fought against fascism; we’ve fought against essentialist notions of identity. And most of that is based on ignorance of other cultures.’

Installation photograph of Yinka Shonibare’s Wind Sculpture (SG) I (2018) in Central Park, New York, in 2018. Photo: Jason Wyche. Courtesy the artist, Public Art Fund, New York and James Cohan Gallery, New York

Shonibare has been keenly aware of this kind of ignorance over the course of his career – but he has turned it resoundingly to his advantage. Born in London in 1962 to a middle-class expatriate family, Shonibare moved back to Lagos at the age of three, returning to London in the mid 1980s to take up a place at the Byam Shaw School of Art. The Cold War was seemingly moving towards a close, and the young student wanted to make a project about Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika – only to be challenged by his tutor: ‘“You’re of African origin, aren’t you? Well why aren’t you producing authentic African art?” […] It was that word,’ Shonibare tells me, ‘that became a catalyst for everything I did. I began to question this notion of “authenticity”.’

At Byam Shaw and later at Goldsmiths, he became fascinated by the work of feminist artists like Barbara Kruger, Nancy Spero and Jenny Holzer, who challenged preconceptions of the kind of work that women were ‘allowed to make’. They did so, moreover, by ‘moving beyond conventional materials’ – as in Kruger’s photo-collages or Holzer’s LEDs. ‘I realised then that I didn’t have to be painting on canvas to be an artist. Painting is so historically loaded, anyway – it’s like a sign of white male dominance.’

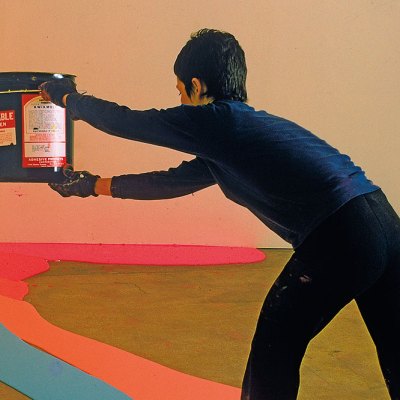

In 1989, Shonibare happened by accident upon a material that is historically loaded in a very different way – one that harmonised beautifully with his fledgling enquiries into the vexed nature of ‘authenticity’. The epiphany came at a street market in Brixton, where Shonibare got talking to a vendor of batik fabrics. He had first come across these colourful textiles as a child in Lagos, growing up during the decade after Nigerian independence; throughout the 1950s and ’60s, they were adopted all over West Africa by those who wanted to ‘distinguish themselves from Westerners in their attire’. But the fabrics themselves are of Indonesian origin; from the 19th century onwards, they were mass-produced by Dutch companies (hence their other name, ‘Dutch wax’), and sold in vast quantities across Africa. ‘The sign of African independence,’ Shonibare discovered on that day in Brixton, ‘is something that was actually fabricated in Europe.’

Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads (1998), Yinka Shonibare. Photo: Stephen White; courtesy National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; © the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

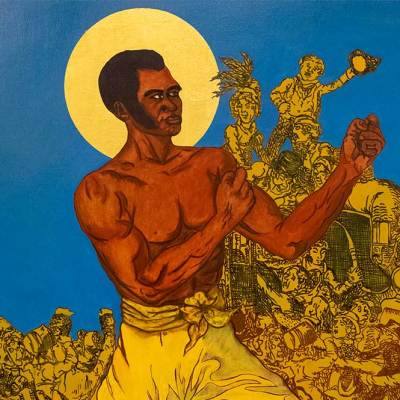

Batik replaced canvas as the support for Shonibare’s paintings of the early 1990s. Works like Double Dutch (1994) comprise small-scale, abstract paintings arranged in a grid – an attempt, Shonibare says, to ‘deconstruct the minimalist language’ of Donald Judd by bringing a ‘craft object’ into the mix. As the critic Rachel Kent has suggested, eschewing the grand scale of modernist art might also reflect Shonibare’s experience as a disabled man (he contracted a virus of the spine in his late teens, which left him partly paralysed) – both as a physical consideration and as one aspect of a deep-seated mistrust of heroic narratives. But it was not long before the artist set his sights far beyond modernism. In 1998, Shonibare made a sculpture after a painting in the National Gallery by Thomas Gainsborough, of the gentleman Robert Andrews and his wife Frances posing proprietorially before the expansive fields of their rural domain. Mr and Mrs Andrews Without Their Heads presents two mannequins: the husband standing with gun and hound, the wife sitting proudly on a bench. Both are bedecked in batik. It has what Shonibare calls ‘gallows humour’ – almost literally, since these headless figures are a ghostly premonition of the guillotines of the French Revolution, less than 50 years after Gainsborough’s painting was completed. It set the tone for a sequence of sculptures after classics of Western art history – such as The Swing (after Fragonard) (2001) and Reverend on Ice (2005), which nods to Henry Raeburn’s Reverend Robert Walker (1755–1808) Skating on Duddingston Loch – each showing the great and the good at play.

Together, these works are an attempt to make visible the histories of violent colonial exploitation that played a part in enabling not only the leisure of the historical middle and upper classes, but luxuries such as ‘good roads, good healthcare’ that modern Western society enjoys today. (More recent works like B(w)anker [2013], which euphemistically portrays the explosive uncorking of a champagne bottle, have made this connection more clear.) However, through the choice of subject matter, the sculptures also reveal the complex contradictions inherent in the way that Shonibare thinks about identity. On one level, they are an appropriation of European history by an artist of African descent. This is Shonibare flouting the rules he was set at art school, and it comes back to what he describes to me as the ‘essential misunderstanding about art and Africans’ – that ‘the African’s encounter with the West doesn’t seem to be recognised’. While Western artists ‘from Picasso to the present’ have been ‘free to be influenced’ by other cultures, there is still an expectation that African artists should ‘remain indigenous’. For Shonibare, ‘If I want to put Victoriana in my work, it’s a statement of freedom.’

Cheeky Little Astronomer (2013), Yinka Shonibare. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Photo: Stephen White & Co; courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman; © the artist

On the other hand, Shonibare identifies himself as a ‘post-Enlightenment person’. The histories that these tableaux satirise are his own – far more so than those of pre-colonial Africa. ‘There’s a lot in indigenous culture that I admire,’ he tells me, ‘and in a sense it is also my own history. But I will never have full understanding of it, because it’s not part of my ritual. You know, clubbing is more a part of my ritual. That would have been my initiation ceremony – going to various clubs when I was young.’

As such, an installation like The Scramble for Africa (2003) – which presents the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, when the leaders of Europe came together to carve up the continent, as the critic Thomas McEvilley once put it, ‘like a side of beef’ – cannot be read as simple satire. Instead, there is something deliciously unresolvable about the relationship between the artist and the work. Is slicing off the heads of Gladstone, Bismarck, King Leopold et al. an act of ridicule – of imaginary recompense? Or, by clothing figures such as these in batik, is Shonibare in fact expressing a certain ambivalence towards them, reflecting his sense that his own identity has been as much shaped by the entanglements of colonialism as it has by his familial roots?

That there can be no real resolution to questions of this kind is something that Shonibare freely acknowledges, even delights in. ‘Often, I don’t know the answers to the things I make work about […] I’m not a politician; I’m not going to put myself forward as the next Jeremy Corbyn. I’m not going to fix it for you.’ It’s clear that political conscience is central to Shonibare’s art – in what might almost be a paraphrase of George Orwell, he tells me that ‘I’d rather just be painting flowers – but I realised that I couldn’t be painting flowers when everything was collapsing all around me.’ Yet he also speaks derisively of ‘overtly finger-wagging’ artists. Throughout his work, high moral seriousness is combined with a genuine pleasure in the frivolity of luxury. In Gallantry and Criminal Conversation, an installation of life-size mannequins commissioned by Okwui Enwezor for Documenta in 2002, the riotous couplings of headless aristocrats poke fun at the stuffiness of the Victorian era (‘criminal conversation’, a euphemism for adultery, was rather more common than they would have had us believe). But they are also a manifestation of sheer desire. ‘You know, I’m not saying that I’m exempt from all this,’ Shonibare tells me. ‘If I had access to huge amounts of money, maybe I’d be some power-crazy person too. In a way, I’m exposing my own human fallibility. You’ve got to be honest about that – and so the works are complex in that they are about desire as well as critique.’

Diary of a Victorian Dandy (03.00 hours) (1998), Yinka Shonibare. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery

This two-facedness, which Shonibare understands as inherent to identity, is the clue to his long-standing interest in the historical figure of the dandy. In 1998, he was awarded his first public commission, a series of photographic works installed on the advertising hoardings of stops on the London Underground. Dressed in a sequence of rakish outfits – his love of fashion runs deep – Shonibare stars as the protagonist of this Diary of a Victorian Dandy, which progresses from an orgy at 03.00 hours to a banquet at 19.00. The series came long before the Art on the Underground programme began, and Shonibare says that people didn’t know what they were looking at – not least because ‘when you look at somebody like Hogarth, if you see any black people in the paintings, they’d be valets. That’s what I was doing there – shifting the central character.’ He identifies with the dandy in part through the figure of Oscar Wilde, ‘who used style to find a position for himself within the British aristocracy – but he was of Irish origin, so he was also an outsider, looking in. And then he was persecuted for his sexuality.’ In another photographic series, from 2001, Shonibare cast himself as Dorian Gray, a character whose dandyism goes far deeper than the politics of status – in fact, explodes the moral high ground from under them. ‘It’s the Jekyll and Hyde thing,’ he says. ‘I’m just as capable of being a monster as the next guy.’

He is quite content to live out any such monstrosity in his fictions. Violence in his work is ‘like blood on stage – it’s ketchup’, and in person he is measured and compassionate, with a keen and mischievous eye for the absurd, but keen also to rail against the ‘elitism’ of the art world, and to offer his solutions. Diary of a Victorian Dandy was the first of many public projects – the most famous being his commission for the Fourth Plinth outside the National Gallery, Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2011) – and for Shonibare public art is primarily a way of reaching people who might not otherwise know where to look (or be able to pay). ‘Cab drivers were always having an opinion [on the Fourth Plinth] – they would say they really liked what I had done, but then they would tell me what they would do instead […] I love being able to encounter that kind of dialogue in public.’ By bringing HMS Victory to face its admiral across Trafalgar Square, but confining it within a bottle to create a kind of monumental miniature, the work itself was intended to be both ‘political and playful’, a gentle nudge in the ribs of the British establishment. But with its billowing batik-patterned sails, the ship was also, quite simply, a decidedly beautiful creation. A love of the aesthetics of motion also underpins Shonibare’s work in film, such as Odile and Odette (2005), based on Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake – but more particularly, the ship prefigured his Wind Sculptures, the first of which appeared in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in 2013. Colourful totems of fibreglass, which have since been installed in New York, Cape Town and Lagos, these works appear to quiver like fabric, making visible the fugitive nature of the elements.

Installation photograph of Yinka Shonibare’s Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2010) on the Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Photo: cooperman/shutterstock

This summer, ‘End of Empire’ will open at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg (27 June–11 October). The first major retrospective since his mid-career survey, which toured MCA Sydney, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in 2008–09, it will bring Shonibare’s career up to date; and in more senses than one, for in response to an increasingly polarised political climate, Shonibare has shifted his sights in recent years from the 18th and 19th centuries to modernity. His tableaux have branched out beyond the European canon in relentlessly inventive ways: heads in the form of globes, taxidermy animal busts, lightbulbs and weather-vanes have been added to the formerly truncated necks, in works which touch on everything from global homelessness to the nature of the four elements. The Salzburg exhibition takes its title from a sculpture of two globe-headed mannequins riding a seesaw (2014) – a comment on the balance of power at the outset of the First World War. It was shown in Margate in 2016 as part of the 14–18 NOW commemorations, alongside The British Library: an installation of shelves stacked with batik-bound books, their spines inscribed with the names of first- and second-generation immigrants who have contributed to British society, from Hans Holbein to Zadie Smith, as well as the likes of Oswald Mosley and Nigel Farage who have argued against immigration. In Salzburg there will also be sculptures from his recent series of ancient Roman statues. Dealing with the misconception that classical marble sculpture was originally unpainted – which gave rise to ideas about the superiority of white statuary, espoused by Johann Winckelmann in the 18th century and now, as Shonibare notes, taken up by the American alt-right – these figures are painted in vibrant patterns redolent of Dutch wax.

Julio-Claudian, A Marble Torso of Emperor (2018), Yinka Shonibare, installed at Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, in 2018. Photo: Anthea Pokroy

I ask Shonibare if he has heard the recent news that Donald Trump wants all federal buildings from now on to be built in the neoclassical style, and the artist – by whose careful, considered speech I could almost have set a metronome until this point – is suddenly stumped. ‘I hadn’t – that’s incredible,’ he says. ‘Does the guy know anything about fascism and architecture?’ He considers a moment, before continuing: ‘It’s funny. The works I’ve made, they actually seem to be more true now than they were when I first made them.’ It’s hard to disagree. But for this artist, the fact that society seems to be going nowhere fast is never a cause for defeatism. Before I have even left the studio, he is heading over to his iPad – perhaps to catch up on Trump’s decree – and I reflect that, through Shonibare’s eyes, our frail old world must seem one endless opportunity for ingenuity, beauty, and a colossal amount of fun.

‘Yinka Shonibare CBE: End of Empire’ is at Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, from 27 June–11 October. The museum is currently closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

From the April 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.