From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

While not as well-known as that of the Achaemenid dynasty (550–330 BC), the second Persian empire ruled by the Sasanian dynasty (AD 224–642) is a pivotal but often overlooked period of ancient Western Asian art and archaeological history. Standing at the cusp of the ancient and medieval worlds, the Sasanian empire was the last great Iranian empire to rule over Western Asia before the coming of Islam, extending at its height in the seventh century from the Nile to the Oxus. Over the course of late antiquity, Sasanian art, architecture, and court culture created a new dominant aristocratic common culture in western Eurasia, beguiling their Roman, South Asian, and Chinese contemporaries and deeply imprinting the later Islamic world.

The arts of Sasanian Iran play a central role in two major upcoming exhibitions due to open in London this spring and Los Angeles next year. ‘Epic Iran: 5000 Years of Culture’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London presents some 350 objects in a survey of Iranian visual and material culture from around 3200 BC to the present day, focusing primarily on small objects, manuscripts and textiles as well as modern and contemporary painting and photography. At the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, ‘Persia: Iran and the Classical World’ (scheduled to open in March 2022), will explore the many exchanges between ancient Iran and the Mediterranean throughout the rise and fall of Iran’s great empires.

Before their rapid ascent to becoming the Iranian kings of kings – an ancient Western Asian imperial title used by the Achaemenids before them – the Sasanians ruled as local kings of the south-western province of Persia amid the ruined palaces and tomb monuments of the first Persian empire. The Sasanians, however, understood their own dynasty to have originated from the ancient and legendary Kayanids, celebrated in the Zoroastrian religion’s sacred texts and in contemporary oral epic traditions. Although the Sasanians were not able to read the Old Persian cuneiform inscriptions, their own Middle Persian inscriptions contain many themes and phrases present in the Achaemenid inscriptions suggesting a robust oral tradition, which amalgamated the historical Achaemenids with Iranian epic and Zoroastrian religious historiography as preserved in the Avesta, the oldest Zoroastrian texts. Like the Achaemenids, the Sasanians understood their empire to spiral out from Persia, and conceived of themselves as battling the forces of evil to set the world in its proper god-given order.

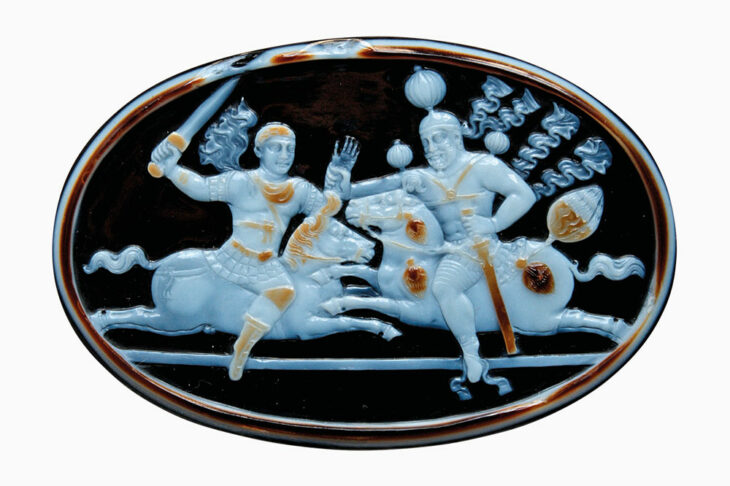

Cameo showing Shabuhr I capturing the Roman emperor Valerian (after 260), Sasanian. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

The Sasanian empire was founded when Ardaxshir I (r. 224–c. 242) revolted from his overlord, the Parthian king of kings Ardawan IV, defeating and killing him in the Battle of Hormozgan. After mopping up resistance in northern Iran, Ardaxshir I took control of the Iranian plateau and pushed into Mesopotamia and Syria, soon bringing him into conflict with the Romans. His son and successor Shabuhr I (c. 242–272) expanded the empire eastward into northern India at the expense of the Kushan empire and westward into Roman territory, raiding several important Roman cities and deporting their inhabitants, including those of Antioch. Turning back several Roman armies, Shabuhr I even captured the Roman emperor Valerian (and held him prisoner until his death in 260), which he celebrated in his later monumental rock reliefs and luxury objects.

Head of a king (c. 4th century), Sasanian. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Ardaxshir I named his empire Erānshahr, the ‘Empire of the Iranians’, adapting the ancient religious concept of the ‘Iranian Expanse’ – the eastern Iranian ‘holy land’ and one of the legendary homelands of the Iranians. While used in a religious sense in early Zoroastrian texts and by the Achaemenids to designate their ethno-ruling class, ‘Iran’ and ‘Iranian’ were employed by the Sasanians for the first time in history in a unitary religious, ethnic, social and political sense. As they took supreme power, they soon laid claim to the more expansive eastern Iranian legacies of the mythological Peshdadian and Kayanid ‘dynasties’ who presided over the first golden ages of the earth as well as fought against dragons, demons and evil non-Iranian usurpers. This mythological history, present in the texts of the nascent Zoroastrian religion, appealed to a wider number of Iranian peoples beyond Persia. After his victories over the Roman armies and successful invasion of northern India, Shabuhr I proclaimed himself to be ‘King of Kings of Iranians and Non-Iranians’.

Despite setbacks, the new empire contended with, and often defeated, the economic and military might of the Roman empire and resisted the military pressures of the steppe while harnessing trade over sea and land. Aided by the reforms of Husraw I, by the late sixth century the Sasanians had forged from heterogenous crown lands, client kingdoms, semi-autonomous city-states, and aristocratic estates a centralised empire. With mercantile networks that extended from the Persian Gulf to the South China Sea, the ‘Empire of the Iranians’ exercised power over Mesopotamia, Iran, portions of the Caucasus, South and Central Asia, and briefly during the empire’s apogee under Husraw II (590–628), Egypt, Anatolia, and Thrace, to the walls of late Roman Constantinople. By the late empire, the Sasanian court had produced an epic history, the Xwadāy-nāmag (The Book of Lords), the inspiration for Ferdowsi’s medieval poem the Shāhnāma (The Book of Kings), which presented the dynasty as the inheritors of an Iranian tradition of kingship that began with the first king of humanity.

Rock relief of Ardaxshir I (r. 224–c. 242) at the Achaemenid necropolis, Naqsh-e Rostam, Iran. Photo: © Matthew P. Canepa

To support their claim to royal power, the Sasanians repurposed and reinterpreted venerable ruins such as the Achaemenid necropolis of Naqsh-e Rostam and the palace of Persepolis, splicing the old ‘Achaemenid-Kayanid’ sites, with new Sasanian monuments, inscriptions and rituals. Parts of Persepolis were rebuilt and served as a fire temple and one of the empire’s coronation sites. At the old Achaemenid necropolis of Naqsh-e Rostam the Sasanian kings carved monumental rock reliefs into the living rock below the Achaemenid tombs. Moreover, Shabuhr I details in an inscription carved into the site’s Achaemenid tower the foundation of a memorial cult centred around sacred fires. Functioning as both reliquary and stage set, they connected the Sasanians not just to historical kings but also to the Iranian past stretching back to the beginning of time.

The Sasanians also built new sanctuaries, palaces and thrones that they presented as primordially ancient. Some had been sacred sites for centuries but were lavishly rebuilt, such as the sanctuary at Kuh-e Khwaja, which marked the site where, according to Zoroastrian eschatology, the Future Saviour would emerge to fight the final battles between good and evil. Others were ‘newly ancient’ sites created ex novo to buttress their burgeoning imperial cosmology and new vision of the Iranian past. For example, the fire at the grand temple of Adur Gushnasp in Iranian Azerbaijan was understood to have existed since the beginning of time, though archaeological investigations prove that the first building phase of the complex commenced only in the fifth century, not coincidentally, around the same time the empire lost control of much of its eastern Iranian ‘holy land’ to Central Asian invaders. In the late Sasanian empire, the Iranian king of kings was understood to reign at the cosmological centre of the earth with other lands and peoples in constellation around him. Sasanian palaces and audience halls encompassed a stunning array of spatial and topographical symbols to manifest this royal vision, and their domed and vaulted palace and temple architecture pushed premodern engineering to its limits. Although it has suffered over the ages, the arch of their main palace in Ctesiphon remains the largest brick arch in existence.

The Great Palace of the Sasanian kings (the Taq-e Kesra) (c. 6th–7th century), Aspanbar (present-day Iraq), photographed by Marcel Dieulafoy before 1888

The interiors of the palace not only modelled Sasanian cosmology but also animated it before the eyes of the king, court, and foreign envoys. Late antique and medieval sources note that Sasanian audience halls and banqueting halls alike contained fixed places, which were specially assigned to each member of the Iranian aristocratic hierarchy, from his high officials to the governors and nobles of the realm, to minor court functionaries. The proximity of a courtier’s place to that of the sovereign manifested his relative stature and importance, and if the king of kings became displeased, a courtier’s place in the audience hall or his banqueting cushions could be moved or removed completely. This spatial map also included places for all the sovereigns of the world as well as members of Iranian courtly society. The four golden thrones provided around that of the king of kings for the emperors of Rome, China, India and the steppe were of course never occupied by any actual emperors, but presented them as servants of the Iranian king of kings who could be rewarded or punished at will like a disgraced courtier.

The space of the audience hall expanded to encompass symbolically not only the seven continents, but also the entire cosmos. Descriptions of miraculous Sasanian thrones or throne rooms appear in a variety of post-Sasanian literary sources, including evidence from multiple corroborating traditions. These include Roman campaign dispatches, reports of the Arab sack of the empire’s sprawling administrative centre in Mesopotamia clustering around Ctesiphon in AD 637, medieval Islamic chronicles and poetic remembrances deriving from Sasanian court propaganda, and later tenth-century eyewitness accounts of the ruins in geographical texts. The audience hall at the sanctuary of Adur Gushnasp (modern Takht-e Solayman) is said to have been equipped with automata to create artificial thunder and rain and portrayed the king of kings in heaven among the heavenly spheres and angels. The enormous throne that Husraw II built in the royal district outside Ctesiphon portrayed the heavens, zodiac and the seven continents in its vault as well as a mechanism that told time, which according to some descriptions, consisted of a vault that moved in time with the night sky.

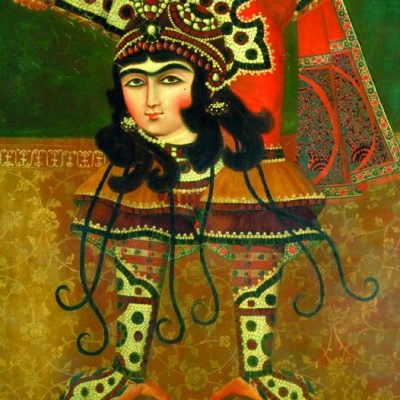

Much like Sasanian art in general, the Sasanian royal image represents the final stage of transformation of the traditions of ancient Mesopotamia, as well as Iranian and Central Asian Hellenism, while marking the emergence of the new medieval visual cultures of the Mediterranean and Western Asia. But compared to the conservatism of the Achaemenid and, for that matter, the Seleucid and Roman imperial image, Sasanian kings revelled in variety and innovation. The Sasanian court produced a repertoire of simple yet powerful themes and iconographies that appear in a range of media. As indicated by coinage, which provides the most complete record of how Sasanian rulers represented themselves, all kings wore a personal crown distinguished by increasingly complex combinations of astral divine symbols, such as solar rays, lunar crescents, stars and wings. According to literary sources each king’s royal costume differed in colour and ornament. The image of the king dominates all aspects of Sasanian art and appears in a wide variety of media, including architectural reliefs in stucco, fresco, silver vessels, rock crystal, semi-precious stones, cameos, seals, and textile. Even enemies grudgingly described the Sasanian sovereign’s court costume as visually overwhelming – and envoys of rival empires counted themselves fortunate to view the Iranian king in his glory, dripping with pearls, glinting jewels and shimmering gold-stitched robes resplendent with representations of supernatural creatures.

Plate with king with the crown of Shabuhr II slaying a stag (c. late 4th century), Sasanian, Iran. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum, London

Sasanian precious metal vessels and silk robes of honour represent two of the great artistic and political traditions of late antique Western Asia. Transmitted materially and reinterpreted conceptually, they were one of the key mediums wherein Roman, Iranian, Indian, Turkic and Chinese tastes commingled and competed over centuries, and the rituals involving their gifting and use survived until the early modern period. Sasanian silver served two primary purposes within and eventually beyond the frontiers of the Persian Empire. A special group of objects were specifically designed to bring the royal image before the eyes of the great and minor nobility in a medium that was intrinsically precious. The most popular types of vessels portrayed the king hunting a variety of quarry. These vessels were, in a sense, portable and distributable monuments, supplementing the static repertoire of the early rock reliefs and offering a variation of the themes known through literary sources and stucco fragments that graced palace interiors and the landscape of the empire.

A larger group of objects played a more practical, though certainly not prosaic role, as tableware for the bazm, the formal banquets in which the ritualised consumption of wine was a prominent feature. While many vessels were created for provincial gentry at their own tables, a small number of objects were gifts from the courts of high officials and even the king of kings. They rendered a courtier socially and politically visible and powerful, albeit always dependent on largesse flowing from the king of kings. In this the vessels were part of the same symbolic order as the banqueting cushions that marked a courtier’s place at the bazm (and, consequently, his social standing), and the rich clothing, elaborate headgear, belts, and jewellery that the king bestowed on them to be worn at table.

Finely woven Sasanian textiles were the envy of the world and their innovative ornamental patterns lived on for centuries after the fall of the empire. Iranian textile ornament became increasingly entangled with Central Asian trends, Sasanian figural ornament being imitated widely by the Sogdians, an eastern Iranian people who were the great mercantile middlemen of Eurasia. Once the empire fell and sumptuary restrictions evaporated within Iran (and associating closely with an enemy became irrelevant), waves of Sasanian-inspired textiles flooded Eurasia and became part of the visual repertoire of power for many who had previously just viewed them from afar. Elites in China, Korea and Japan all prized Iranian silver and glass and a comparison among objects found in tombs and temple treasuries around the Sea of Japan illustrate this transregional and transcontinental aristocratic taste for Iranian luxury tableware, silver and silk.

Textile portraying a creature symbolic of the Iranian Royal Fortune (xwarrah) (7th–8th century), Eastern Iran. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In the face of the inexorable advance of the Arab armies through the Iranian Plateau, the last Sasanian king, Yazdgerd III, fled towards China but was killed in 651 in Merv. His sons and descendants lived on as a court in exile in China, serving as Tang officials for several generations. Despite Islam’s subsequent expansion into eastern Iran and Central Asia, Iranian aristocratic traditions lived on among local Iranian elites in the highlands of the former Sasanian Empire and in Sogdiana, and the Abbasid caliphs looked to Sasanian court protocols for inspiration. More importantly, Sasanian kingship became the touchstone for the development of later royal and aristocratic identities under Islam in Iran and Central Asia as breakaway states emerged from the Caliphate’s sprawling holdings. With Persianate culture as an aristocratic common culture from the Balkans to Bengal, the early modern empires of the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals all shared an appreciation for Persian culture and this ancient heritage. The Sasanian dynastic history became the ultimate historical referent, joining Islam as a source of legitimacy for Muslim kings as well as a framework for understanding interstate relations and the cosmic order, and for living a noble, cultivated life.

‘Epic Iran’ opens at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, on 29 May 2021.

From the February 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.