From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

From the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean to the Paris suburb of Saint-Denis, the French Republic is staging a nationwide exhibition designed to save the young from the prejudices of their parents. It is called ‘The Arts of Islam: A Past for a Present’ (until 27 March), and each of its 18 participating venues contains 10 works intended to challenge the image of joyless Islamic bigotry internalised by many French people – the polls concur on this – in the culture wars of recent years.

Instead these installations show Islamic civilisation’s suppleness, its love of luxury and the generally benign nature of its dealings with Christianity and Judaism. They also show the surprising ability of a law-based society to selectively disregard restrictions on sex, booze and human representation in art – to sin, in other words, while not negating the essence and even the practice of the faith.

Among the exhibits are a lacquered Iranian pen box embellished with pale women in European-inspired décolleté, a 16th-century Turkish miniature of the Archangel Gabriel appearing to the Prophet Muhammad and a statuette of a lion made in Fatimid Egypt and conserved for hundreds of years in a church in the Auvergne. What qualifies such apparently unconnected pieces for inclusion in the same exhibition? The answer lies in modern France.

Some of the posters for the 18 exhibitions organised by the Islamic art department of the Louvre across France.

The past decade has seen Charlie Hebdo, Bataclan and the beheading of a teacher, Samuel Paty, for showing his pupils caricatures of the Prophet. French troops have fought French jihadists in the eastern Mediterranean and the Sahel. Nativists have rolled up their sleeves for the civilisational struggle that Samuel Huntington promised for America but which has found its natural place on the other side of the Atlantic. Mugged first by Marine Le Pen and latterly by Éric Zemmour, the polity, including the administration of Emmanuel Macron, has staggered rightwards.

And now, as the president enters re-election year campaigning hard against Muslim ‘separatism’, as he goes after religious home-schooling and foreign-trained imams, as poll after poll suggests that most voters regard Islam as incompatible with French values, come these little shows with big ambitions.

It’s the variety one finds within the various ensembles – their mixture of the sacred and profane, the frivolous and the deeply serious – that makes ‘The Arts of Islam’ potentially significant. In the installation in the riot-prone suburb of Saint-Denis (where the interior minister only recently shut down a mosque for six months), a 15th-century brass key to the Kaaba, the cube in the middle of the Mecca sanctuary towards which all Muslims turn in prayer, is in proximity to a mildly pornographic painting of a Iranian lady in see-through blouse and a set of Hebrew house charms from the Jewish quarter of Fes in Morocco. This juxtaposition alone defies the communitarian vision of the faith that is peddled by Islamist ideologues in neighbourhoods where the state fears to tread. It silences the dog whistles of the nativist Right, which thrills its supporters by describing the history of Islam as a chronicle of bigotry and social control.

Yannick Lintz, the director of Islamic art at the Louvre, took the idea of simultaneous exhibitions to the prime minister, Jean Castex, shortly after the murder of Samuel Paty. Curators and art historians across the country; mayors, imams and teachers; all were mobilised in a common effort to adapt venues, select pieces and prime the public. This being febrile France, much thought went into the avoidance of misunderstanding. Not a gem-encrusted dagger has entered a display cabinet without the disclaimer that it was never intended for use – it was just for showing off.

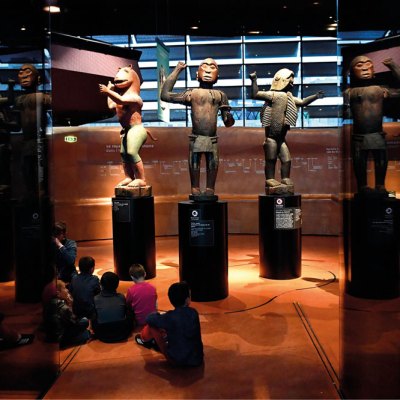

As befits any French bureaucratic effort, there is a template to follow. Whether it is a public library, an hôtel particulier or a medieval hospice, all 18 exhibition spaces have the same large screen (4m by 2.5m) showing the same sequence of historic Islamic cityscapes on a loop and flexible seating for up to 30 people (foldable stools, lightweight sofas) to encourage them to take the weight off their Stan Smiths and parse the art. Each work is accompanied by a panel explaining in deliberately simple French what it is, a map showing its place of origin and what Lintz calls an ‘image of contextualisation’, a visual prompt to encourage schoolteachers to riff – to the extent that the guardians of laïcisme are capable of doing this – on the joys of Islamic culture. Each visitor receives a pamphlet that briefly introduces Islamic civilisation before giving information about the pieces displayed in the venue in question. Admission is free.

Each space shows one work by a modern artist. Katia Kameli’s video piece takes as its subject a kiosk in Algiers where nostalgic photographs are displayed and sold. The black-and-white shots of sunlit modernist buildings and smiling, trustworthy politicians and her interviews with fellow citizens who try to tell her what it is about the kiosk and its wares that draws them back, but cannot quite put their finger on it, create an atmosphere of historical recrimination and loss. The Iraqi Kurdish photographer Hiwa K shows us a breeze-block structure in the middle of a desiccated Middle Eastern landscape, calling it One Room Apartment.

Installation view of the ‘Arts de l’Islam’ exhibition at the Maison Folie Hospice d’Havré, Tourcoing

In the installation at Tourcoing, near the Belgian border, primary schoolchildren can spend an hour stenciling tote bags with the silhouette of a mosque lamp or of the hand that Shias associate with one of their martyrs. And this is another feature of ‘The Arts of Islam’: the different strands of Islam – Sunni, Shia and Sufi – are mixed up impartially and in defiance of the tensions that exist between them. That there is no single Islam, just as there is no single France, seems to be the message Yannick Lintz wants us to take away.

Baby steps, to be sure, against years of prejudice and misinformation. Lintz and her colleagues have assumed an impossibly heavy burden and, whatever the success of the exhibition – when I spoke to her in January she told me she had received encouraging reports from fellow curators around the country – it will count for little if the message isn’t taken into schools, mosques and the homes of ordinary people; if the monopoly of knowledge that the bigots have arrogated to themselves isn’t challenged.

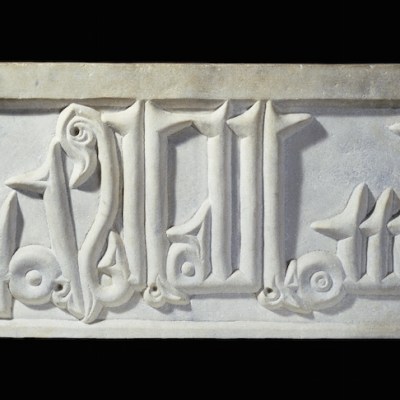

Lintz is content to change minds one at a time. ‘When a young Frenchman of Muslim origin turns to his non-Muslim schoolfriend in the exhibition and, indicating some calligraphy, says, “I can read that”; when the friend looks back at him with surprise and respect; then we know we are getting somewhere.’

Many of the 180 pieces on display are loans from the Louvre, where the high-concept Islamic department, €99m of undulant glass and metal shimmering in the Cour Visconti, was inaugurated amid a deluge of self-congratulation in 2012 (before Lintz’s time). Among the more optimistic predictions that were heard was that by honouring the achievements of Islam, the Louvre would help close the fracture sociale between the country’s increasingly alienated Muslims and the uncomprehending rest. But people don’t like being talked down to, certainly not from a palace.

Even then, the influential art historian Rémi Labrusse was a sceptic of the museum’s big statement. He excoriated it for colluding in stereotypes (veils; dunes; magic carpets), and for taking petrodollars from ‘certified tyrannies’ such as Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan. The new department, he feared, would not so much aid mutual understanding as foster ‘a pseudo-world of dreams yoked to the past on the one hand, and on the other a present that is caricatured, inviting repulsion and rejection’.

Labrusse is on the scientific committee of ‘The Arts of Islam’ – and the exclusion of central Paris from the list of venues certainly deals with any suspicion of velour-lined metropolitan smugness. No petrodollars, either, and no loans – just 180 pieces acquired by the French state through the usual, far from unimpeachable means: war, commerce, diplomacy, colonisation. The cost of staging all 18 iterations of the exhibition amounts to just €4m. The France represented in this exhibition is not a country strutting for the world but one looking in on itself and saying enough is enough.

There is a book of short scholarly articles accompanying the exhibition. As Nourane Ben Azzouna of Strasbourg University points out, while the Quran condemns polytheism and idolatry, and forbids any depiction of the divine, from the 13th century images of Muhammad and other prophets began to appear alongside devotional texts – to start with, his face visible and only later veiled from view. Lintz herself discusses recent archaeological finds in southern France – Muslim graves, a kiln for making pottery in the Islamic style – that support the idea of substantial Muslim communities living there in the Middle Ages. There is a ‘French Islamic heritage that is deeply anchored in our history’.

In the same volume, the curator Ariane Dor reminds us that alongside the secular commerce in carpets, metalware and other luxury goods that flooded into Europe from North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean, another trade was going on, this one to the glory of God. Prizing reliquaries made of Egyptian rock crystal – which was valued for its transparency and associated with purity and light – and chasubles of Andalusian silk, the Catholic Church was a loyal customer for luxury goods from the Islamic world. All this between Crusades, between denunciations of the imposter Muhammad.

The book of the exhibition may be read by few. More significant is the exhibition floor. And it is noteworthy that in the introduction to the pamphlet that every visitor receives are the same two images: one showing a haloed Muhammad preaching to his followers and another an Iranian Shah enjoying a moment of intimacy with a page. That Islam hates artistic depictions of the human form and is as a consequence implacably hostile to modern notions of the individual; that it is doomed by its own prescripts to a hopeless, antiquated homophobia: here, in two images, the lies are exposed.

Although both pieces are owned by France, neither is exhibited in ‘The Arts of Islam’ – perhaps out of fear of perishability, or the ever-present if unspoken dread of defacement. Whatever the truth, it is tantalising to speculate that by giving a copy of these images to every person, young or old, Muslim or non-Muslim, who comes through the door, ‘The Arts of Islam’ might achieve something that France’s temple to culture, its Kaaba in metal and glass, could not.

Christopher de Bellaigue is the author of The Islamic Enlightenment: The Modern Struggle Between Faith and Reason (Vintage). The Lion House, the first of a trilogy about the life and court of Suleyman the Magnificent, will be published in March.

From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.