In the decade after Dan Flavin’s (1933–96) death the artist’s posthumous reputation was secured with the world tour of ‘Dan Flavin: A Retrospective’. The exhibition began in 2004 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (in partnership with the Dia Art Foundation) and ended on the opposite coast, at LACMA in 2007, with intervening stops at Fort Worth, Chicago, London, Paris, and Munich.

Since then there have been several focused exhibitions that have concentrated on more unfamiliar aspects of Flavin’s work, such as the revelatory drawings show that began at the Morgan Library in 2012 and the current display of the early icons series (1961–64) at the Dan Flavin Art Institute in Bridgehampton, New York, which runs until next spring.

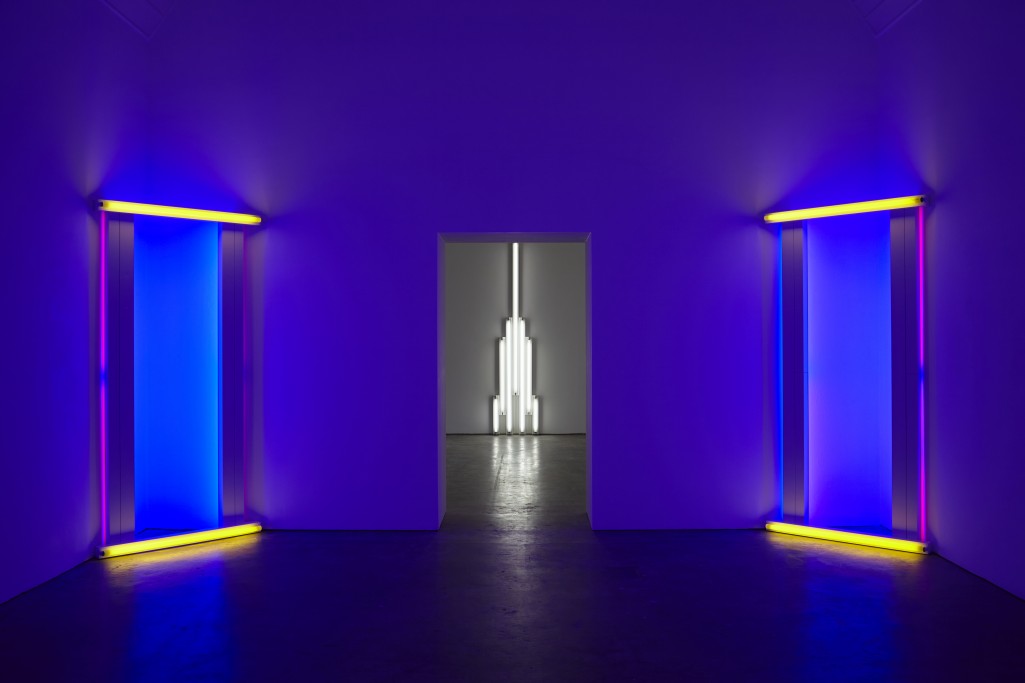

untitled (to Cy Twombly) 1 (1972), Dan Flavin. © 2016 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York London

And now, the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham is presenting an exhibition called ‘It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else’. Despite the blunt title, taken from a forthright statement by Flavin himself, the gallery notes carefully explain that this is ‘not a didactic museum show, but rather an exercise of matching a judicious selection of Flavin’s work with the variety of interiors that Ikon Gallery has to offer’. It’s an unnecessarily defensive note to strike for an exhibition where the bold installation more than lives up to the show’s title.

In the first gallery, pink out of a corner (to Jasper Johns) (1963) is placed in the left-hand corner, while visitors enter from the right, so you see the pink-lit room before you can identify the light source. From this gallery, which opens on to the next space, alternate diagonals of March 2, 1964 (to Don Judd) (1964) is visible straight ahead of you, but not the artworks placed in the left-hand corner or on the right-hand wall. Round the corner is untitled (to Don Judd, colourist) 1–5 (1987), a sequence of five sets of tubes (pink, red, yellow, green, and blue), each topped with two pink tubes to form a T.

untitled (to Don Judd, colorist) 5 (1987), Dan Flavin. © 2016 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London

Flavin once said: ‘Everything is clearly, openly, plainly delivered. There is no overwhelming spirituality you are supposed to come into contact with.’ Metaphysical interpretations may have come too easily to contemporary critics who knew that Flavin had once trained for the priesthood, but here at Ikon such protests are subtly undermined. The first-floor spaces are white cubes, but the second-floor galleries of the Victorian neogothic building retain their original ceilings. Placed in the corner of the latter is untitled (to Cy Twombly) 1 (1972), which consists of two 8ft white fluorescent tubes pinned to each other in the shape of a cross, one tube facing the gallery, the other facing the corner.

Unlike his Californian Light and Space near-contemporaries, Flavin was uninterested in creating an environment. In fact, he fiercely resisted the term, explaining: ‘It seems to me to imply living conditions and perhaps an invitation to comfortable residence.’ He was more comfortable describing his artworks as ‘situations’, which in some way transformed the place in which they were shown. The placing of four ‘monuments’ to Tatlin (part of a series made between 1964 and 1990) under Ikon’s vaulted ceiling makes the gallery seem grander while emphasising Tatlin’s role as a failed revolutionary…

And while the fluorescent light pieces continue to transform the spaces in which they are installed, time is changing how we see the pieces. On the side of many of the fluorescent tubes is the manufacturer’s label, which shows that these ordinary commercial lights came from Passaic, New Jersey. We must be nearing the time when, in the minds of gallery goers, strip lighting in the outside world will bring Dan Flavin to mind. (One suspects, however, that part of the artist would have been amused by the EU ruling that declares his works as light fittings for VAT purposes.) The shift is a useful reminder that ‘It is what it is’ is not a straightforward statement at all, when ‘what it is’ is changing all the time.

Flavin once told an interviewer that ‘All posthumous interpretations are less,’ but in its current exhibition of his work, the Ikon Gallery strongly suggests that, in the right hands, this needn’t be the case.

‘It is what it is, and it ain’t nothing else’ is at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 26 June.