From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The artistic movement known as Spatialism was founded by the Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana. In his Manifiesto bianco, co-written in 1946 with his students in Buenos Aires, Fontana declared that the post-war era required a new art. Freed from traditional painting and sculpture, and responding to ideas derived from modern physics, this art would be a synthesis of reason and the subconscious, encompassing the four dimensions of time and space. ‘We imagine synthesis,’ the manifesto explains, ‘as the sum total of the physical elements: colour, sound, movement, time, space, integrated in physical and mental union.’

Born to Italian parents in Rosario in Santa Fe, Argentina, in 1899, Fontana trained as a sculptor. Moving between Italy and Argentina in the 1920s and 1930s, he experimented in painting, drawing and sculpture, both abstract and figurative. On 5 February 1949, he presented his Ambiente spaziale a luce nera (‘spatial environment with black light’), a temporary installation with a giant neon-lit amoeba-like shape suspended in a darkened room at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan. The same year he also worked on his first Concetto spaziale (‘spatial concept’), a painted screen punctured by a sequence of holes. The gesture has been acknowledged ever since as revolutionary, breaking through the illusory universe of the two-dimensional painted surface to acknowledge the infinities beyond our schooled perceptions. ‘These Buchi,’ Fontana wrote in 1963, ‘are an indication of the nul, of the void.’ A series of pierced works were followed in 1958 by the first of the Tagli: layered, monochromatic canvases with slits or gashes, backed with black gauze. These opened two-dimensional painting into an enigmatic fourth dimension and turned the still image into the record of a violent action. Having issued further manifestos between 1947 and 1952, Fontana continued to create work pursuing these ideas until his death in 1968, winning the international Grand Prize for Painting at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966 for an installation of 20 white canvases, each with a single vertical incision.

Luigi Mazzoleni, of the Turin- and London-based dealership Mazzoleni, says: ‘Fontana has always had a strong market. In the early 1970s you could buy an apartment for the price of a Fontana painting. In the last decades that market has become more global – South Korea, Japan, China – though the US is the primary market.’ The market for Fontana’s work reached an alltime high in November 2015, when one of his egg-shaped works from the early 1960s, the sun-yellow Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (‘spatial concept, the end of god’, 1964), was chased to $29.2m at Christie’s New York. This toppled the previous record two years earlier, in the same house, of $20.9m for a work of the same name from 1963. According to Alessandro Diotallevi, a specialist in the post-war and contemporary art department, when Christie’s started its dedicated Italian sales in 2000, Fontana’s record stood at just over $1m. The rise is partly attributable to the many focused sales of Italian 20th and 21st-century art mounted by Sotheby’s and Christie’s since; but exhibitions such as the landmark retrospective at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2014, and ‘Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold’ at the Met in 2019 tended also, Diotallevi thinks, ‘to galvanise the market’. Most sought after are the Fine di Dio works (1963–64), of which there are 38, and the 22 Venezia pierced paintings created in a rush of inspiration in 1961. Although the post-war Italian market has undergone a strong correction since 2018, Fontana’s value holds. A white Fine di Dio spatial concept from 1963 fetched $20.6m at Sotheby’s New York in November 2023, against an estimate of $18m–$20m. Mazzoleni recalls that when ‘the world stopped’ in March 2020, the only works they could sell online were Fontana’s slash paintings: ‘They are iconic.’

Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (1963), Lucio Fontana. Sotheby’s New York, $20.6m

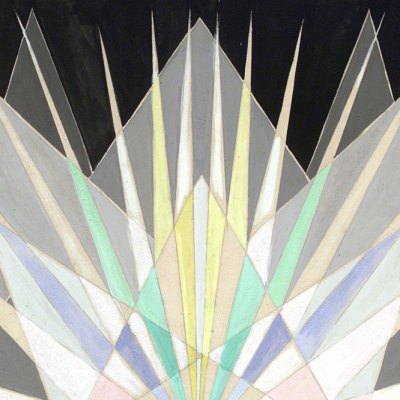

Fontana inspired younger artists, who took Spatialism in different directions. Chief among them were Piero Manzoni (1933–63) and Enrico Castellani (1930–2017), founders of the experimental gallery Azimut in Milan in 1959. The radically inventive Manzoni worked with many materials, but collectors, Mazzoleni says, look for his ‘achromes’, particularly the larger ones, created between 1957 and 1963. These poetic painting-like objects consist of canvas squares soaked in kaolin – china clay – and draped to dry with wrinkles intact. Manzoni explained, ‘My intention is to present a completely white surface (or better still, an absolute colourless or neutral one) beyond all pictorial phenomena, all intervention alien to the sense of the surface.’ A retrospective mounted by Gagosian in New York in 2009 pushed him to prominence. His auction record was set in 2013 at Christie’s New York for Achrome (1958), which reached $14.1m against a $6m–$9m estimate.

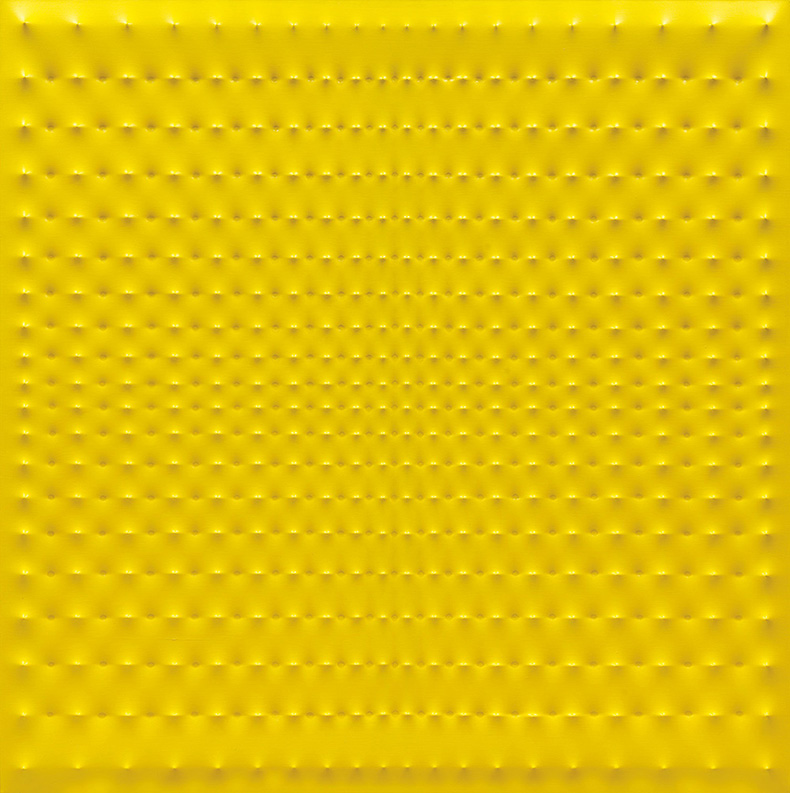

Castellani discovered his unique approach in 1959 when he stretched a monochrome canvas over a pattern of hazelnuts (later replaced by nails), creating peaks and depressions that play with the light. According to Carolina Lanfranchi, a specialist for Phillips based in Milan, ‘Castellani’s works from the 1960s are most sought after.’ She cites the £321,000 paid at Phillips London in October 2018 for Superficie Gialla Tokyo no. 2, from 1967, against an estimate of £250,000– £350,000. The record, set in 2014 at Sotheby’s London, is £3.8m (estimate £1m–£1.5m) for the very large Superficie Bianca, dated 1967, bought by the vendor directly from the artist in 1969. It had been commissioned for Gio Ponti’s architectural gesamtkunstwerk, the villa Lo scarabeo sotto la Foglia in Malo (1964–69). Marco Voena of London dealership Robilant + Voena says that the extraordinary boom in the market for these artists from 2010–18 has subsided, but they have worked hard to find alternative markets, most recently mounting the exhibition ‘The Infinity of White: Lucio Fontana and the Italian Artists of the Absolute’ in Oman (1 February–31 March). Voena says, ‘These monochrome, abstract art works are for all cultures.’ In particular, they appeal to collectors in the Middle East, where ‘the light is very dramatic’. He notes that the artist Agostino Bonalumi (1935–2013), whose prices used to lag behind Castellani’s, is seeing strong market interest (his auction record, from 2014, stands at £626,500 for Bianco, 1966, sold at Sotheby’s London against a £300,000–£500,000 estimate). Bonalumi extrapolated from Fontana’s work using what he called ‘extroflexions’ – intricate stretchers that moulded his vinyl-coated monochromatic canvases from beneath. It is also his work from the 1960s that is most highly valued. Voena says, ‘This is a unique language, very close also to design.’

Superficie Gialla Tokyo no. 2 (1967), Enrico Castellani. Phillips London, £321,000

Another associate who benefited from the earlier auction focus is Paolo Scheggi (1940–71), who continues to sell, Voena says, though for lower prices than before. Again it is the daring work, his Intersuperficie series of superimposed monochromatic canvases with decisive geometric cut-outs, which date to the 1960s, that retain their appeal for collectors. Phillips London offered his Intersuperficie curva-dal bianco cerchi progressivi-regressivi from 1965 in its 20th Century & Contemporary Art Day Sale in March (estimate £80,000–£120,000). His Eclisse (1969), white, with overlapping circular apertures, sold in 2017 at the same house for £525,000 against a £300,000–£400,000 estimate.

James Mayor, of London’s Mayor Gallery, has been a supporter of two further artists associated with the movement, Eduarda Emilia Maino (1930–2004), known as Dadamaino, a member of the Milanese avantgarde, and Turi Simeti (1929–2021), originally from Sicily, who exhibited in Milan from the 1960s. ‘We only handle works by Dadamaino from 1958, 1959 and 1960,’ Mayor says. ‘This was the most interesting work.’ He adds, ‘When I first saw the black and white volumes with the holes, I really saw the potential, if you frame them to reduce the fragility, to appeal to American collectors of artists like Ellsworth Kelly or Eva Hesse.’ Simeti continued to make his three-dimensional extroflexed monochromatic canvases, with their dynamic patterns of ovals, throughout his career. Mayor says, ‘They become increasingly three-dimensional, increasingly beautiful.’ The market is steady, consistently reaching five figures.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.