For an object that had for some years served as the roof to a hen house, Vanessa Bell’s collage portrait of family friend Molly MacCarthy (1914–15) is in surprisingly good repair, the scratches and marks that constitute its various imperfections as likely to have been made deliberately by Bell as by rough treatment. Thought to be the earliest example of pure collage made in this country, the work followed Bell’s trip to Paris and to Picasso’s studio in 1914, and is one highlight in a small show of works by Bell and Duncan Grant at Piano Nobile. Rarely if ever seen before in public, the 32 works on show date from 1910 to 1934, roughly spanning the period from the opening of the Omega Workshops in 1913, to the pair’s most productive years at Charleston.

Portrait of Molly MacCarthy (1914–15), Vanessa Bell. Image courtesy Piano Nobile

If Bell’s reputation as a radical has been endangered by her status as a lifestyle icon, the portrait of Molly MacCarthy is a reminder not only of her ready engagement with the European avant-garde, but her own distinctive – often original – interpretation of its developments. The work includes fragments of newspaper, recalling the collages being made by Picasso and Braque at around this time. While for Picasso, such ‘real’ material served to suggest an extra dimension, by forcing it into a collision with representational elements, for Bell (and indeed Grant), it is almost impossible to tell to what extent newspaper was a considered choice. Instead it takes its place in a catalogue of papers of varying weights and qualities, painted roughly in gouache or oil, and cut into sharp, irregular pieces. As much as the shards of paper describe a shattered image that recalls cubist painting, Bell’s collage has a character of its own, and is more like a mosaic, or a stained-glass window, than anything that Picasso ever produced.

Interior at Gordon Square (c. 1914–15), Duncan Grant. Image courtesy Piano Nobile

Also on view at Piano Nobile is a collage by Duncan Grant entitled Interior at Gordon Square (c. 1914–15) which, like Bell’s Portrait of Molly MacCarthy, is loosely based on an earlier painting. Grant’s collage explores the pictorial potential of the technique, its material qualities introducing a tension into our perception of it: the piece switches constantly between a flat, abstract arrangement of shapes and colours, and a construction with a remarkably complex sense of space and depth. The technique of collage also served as an aid to composition, and was used by Grant in his design for a fire screen: the preparatory collage and the finished fire screen are exhibited here for the first time since they were made. Meanwhile, Bell’s painting from 1915, Still Life: Wild Flowers, pieced together from blocks of colour, seems surely to have been made with collage in mind.

The parallels in the pair’s work suggest both the creative atmosphere at Charleston, where Bell lived with Duncan Grant for some 45 years before her death in 1961, and the nature of their relationship as a close artistic partnership. Grant’s portrait of Lytton Strachey from 1913 is striking in its similarities to Bell’s better-known portrait from the same year: in fact they were both painted at the same sitting, as Strachey posed reading in the garden at Charleston. While Bell emphasises Strachey’s interior life, Grant’s portrait points at his subject’s relationship with those around him. Absorbed in his book, Strachey is at once solitary and part of a group; the embrace of the chair and of the curving wall behind him draw the subject towards us even while his attention is focused elsewhere.

Lytton Strachey (1913), Duncan Grant. Image courtesy Piano Nobile

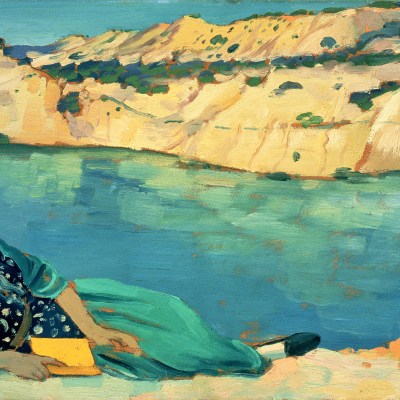

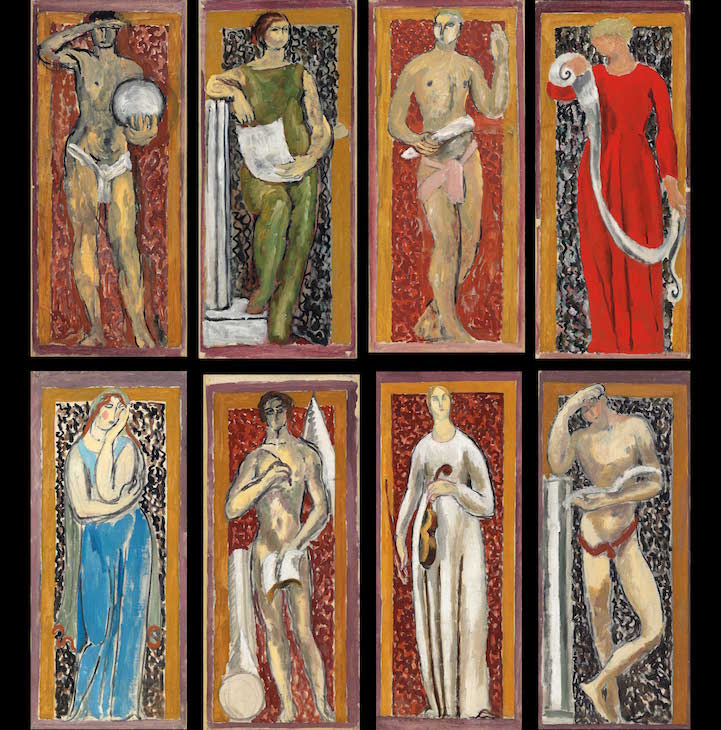

As directors of the Omega Workshops, begun by Roger Fry in 1913, Bell and Grant were accustomed to working together, a pattern that continued beyond the Omega years, when they collaborated on a number of domestic decorative schemes. The pair were commissioned to produce eight decorative panels depicting the Muses of the Arts and Sciences for John Maynard Keynes’s study at Cambridge, to complement the mural painted there by Grant in 1910. Bell took the female figures and Grant the male, but as the set of oil studies for the panels show, their execution is so similar as to make it hard to distinguish each individual hand.

Studies for The Muses of Arts and Sciences (1920), Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Image courtesy Piano Nobile

If the classicising tendencies of these panels point to a softening of the pair’s early radicalism, the rediscovery of a later collaboration – a set of dinner plates commissioned in 1932 by Jane and Kenneth Clark as part of a dinner service – might suggest otherwise. Feared lost for the past 30 years, the plates re-emerged last year following the solo Vanessa Bell exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery. Depicting 48 famous women, including writers, actresses and queens, the set outlines a feminist history that is as telling in its inclusions as its omissions. Women artists are barely represented, reflecting how little had been written on the subject. But among their depictions of famous beauties, Bell and Grant favour Nell Gwynne, a woman of humble origins and great character, above the aristocratic ladies in the court of Charles II. While Kenneth Clark was somewhat ambivalent towards the finished plates, Jane seems to have been far more enthusiastic. She was closely involved in the commission as it developed, suggesting that it was she rather than her husband who was the driving force behind the project.

Woman in a Red Hat (c. 1915), Vanessa Bell. Image courtesy Piano Nobile

Having only just come to light, the plates are exciting new material for research and discussion. They are the subject of a two-part feature in British Art Studies, which includes a forthcoming filmed discussion with artist Judy Chicago (of The Dinner Party, completed in 1979). In her catalogue essay for the Piano Nobile exhibition, Hana Leaper has only just begun to unravel the many intricate connections that tie the women on the plates not only to each other, but to Bell, Grant and the Bloomsbury Group. Also exhibited for the first time at Piano Nobile is Bell’s painting, Woman in a Red Hat (1915) – another new discovery of the artist’s work. Coming so soon after Dulwich Picture Gallery’s major reassessment of Bell’s career, it suggests that this is an artist whose significance is perhaps only just beginning to be fully recognised.

‘From Omega to Charleston: The Art of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant 1910–1934’ is at Piano Nobile, London, until 28 April.