From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When James Barnor (b. 1929) set up his first photography studio in Accra in 1953, he named it after the secret grove inhabited by the Norse goddess Idunn, whose magical apples granted eternal youth to wandering heroes. At the age of 24, Barnor had just found a large room to rent on the harbour near Accra’s famous Sea View Hotel. He’d acquired his first camera six years earlier, and undergone an apprenticeship with his cousin J.P.D. Dodoo; since 1949 he had been snapping clients with his uncle’s old plate camera in front of a backdrop he hung outside his family’s apartment. But Barnor had now moved into an indoor studio with electricity – one of only three or four in the city at that time. As he cast around for a name, he landed upon a memory of learning about Idunn’s grove from his schooldays – and made a link with the painstaking exercise he had honed of spending ‘an hour and a half on one face alone with a very sharp pencil, retouching fine lines […] I thought that if someone came in, I’d make them look younger. So, if I open a studio, what should I call it? Ever Young.’

A number of the earliest photographs to come out of Ever Young are included in the retrospective ‘James Barnor: Accra/London – A Retrospective’ at the Serpentine in London (until 22 October). Newlyweds beam; a toned torso contorts into what looks like a yoga position; an infant stretches out on all fours like a cat. Beatrice, an early subject, poses with a toy figurine Barnor acquired for training the camera’s focus. Whereas the other professional studios in Accra were run by ‘elders’, Barnor created something new – more like a social centre for the city’s young people. Dances hosted at the Sea View at the weekends would be fuelled by drinks bought from the bar, and the revellers would have their portraits taken afterwards, in the small hours.

‘Everything in My Hand’ (c. 1953), James Barnor. Courtesy Autograph

Alongside his studio practice, Barnor worked for the Daily Graphic from 1950 onwards. ‘I went wherever there was news,’ Barnor has said of this time; it just so happened that at the time there was rather a lot of it. These were the years in which Kwame Nkrumah was beginning to stoke popular support for the movement that would see Ghana gain independence from the British in 1957. As Nkrumah would tell the UN General Assembly in 1960, it was ‘the dawn of a new era’.

Barnor knew Nkrumah well and photographed him often, whether in his pomp at the independence celebrations or kicking a football around before an international match in 1952. His pictures of that era take in a host of other political and cultural figures, from the opposition leader J.B. Danquah to the boxer Roy Ankrah. When I speak to Barnor on the phone, a few days after his 92nd birthday, he tells me of the heady thrill of those days, capturing the arrival of the new dawn as the first professional photojournalist in the country. ‘The idea was that if you took a photo of a fight, you’d better have it developed by the time the fighting had finished!’, he says.

He is delighted with the Serpentine exhibition – ‘a fine example to set the younger generation’, he calls it. It’s his first museum survey in London – where he has lived since the 1990s, and where he took many of his best-known photographs in the 1960s, depicting the lives of Black Londoners in a series of commissions for the South African magazine Drum. As its title suggests, the show follows Barnor from Accra to London – but also back again: he first came to the UK in 1959 to study and stayed on; a decade later, he returned to the city of his birth, working to promote at home the new techniques of colour photography he had studied abroad.

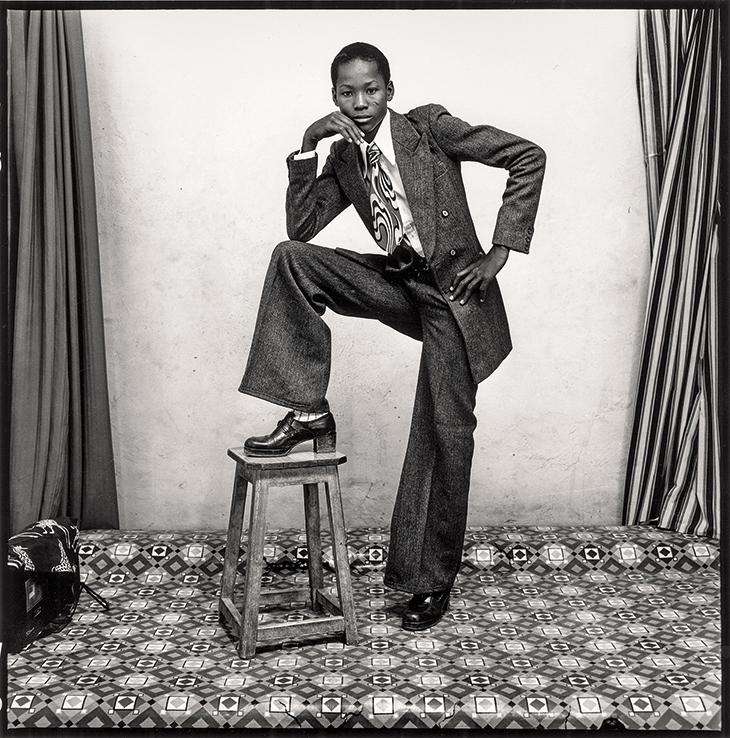

Les trois yéyés avec pattes d’éléphant (1977), Malick Sidibé. Courtesy MAGNIN-A Gallery, Paris; © Malick Sidibé Estate

Renown beyond Africa may have arrived late for Barnor, but his reputation now seems assured; he is part of that generation of mid-century photographers across West Africa whose work has come to represent the new reality of the post-colonial moment. In Mali, there was Seydou Keïta (1921–2001) – whose careful choreographing of costume and backdrop, snazzy patterns combining with artful casualness to communicate style and poise, established him as the chronicler of modern, sophisticated Bamako – and his younger contemporary Malick Sidibé (1935–2016), who depicted teens at nightclubs, or sunbathing by the riverbank, in similarly meticulous compositions. In Senegal, Mama Casset presented Dakar after the war as a languorously glamorous city; while in Kinshasa, Jean Depara recorded the pleasures of everyday life with his images of dancehalls and swimming pools.

Portrait of a woman (c. 1950–60), Mama Casset at this Studio African Photo in Dakar. Courtesy Revue Noire; © Estate of Mama Casset

The Anthology of African and Indian Ocean Photography (1998), published by the French publisher Revue Noire, helped to bring many of these photographers to the attention of the West, just after the first Parisian retrospectives, at the Fondation Cartier, for Keïta in 1994 and Sidibé the following year. The growing appreciation of the work of these two photographers, in particular, has often led to them being described as the ‘fathers of African photography’ – but the Anthology’s remit was altogether broader, stretching back to the 19th century and the earliest days of the medium on the continent. The efforts of Revue Noire have done much to dispel the misconception that photography in West Africa prior to 1950 was solely conducted by outsiders, training an ethnographic gaze on African subjects. In 2015, building on this work, Giulia Paoletti and Yaëlle Biro curated ‘In and Out of the Studio: Photographic Portraits from West Africa’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, drawing on images in the museum’s Visual Resource Archive.

Through these efforts, the picture that has emerged of photography in Africa is one in which members of the ‘golden generation’ did not emerge from a vacuum. Rather, each drew on (and to various degrees reacted against) established traditions of studio portraiture, which had long ago diverged from the European example. Barnor tells me of having been trained in his craft twice – once by his cousin Julius Aikins, who encouraged him in his early experiments with a portable Kodak Baby Brownie, and before then via his apprenticeship with Dodoo, who inducted him into the laborious processes of wet-plate photography.

Cameras first appeared in West Africa in the hands of French colonial officials who were amateur daguerreotypists, such as Jules Itier in the early 1840s – just after the invention of the medium itself – but they were not the preserve of Europeans for long. In 1852, Augustus Washington – the freeborn son of an American slave, who had learned daguerreotype to see himself through college – emigrated to Liberia; he opened the first studio on the continent in Monrovia in 1853, creating idealised images of life in Africa to entice African Americans to come and join. Washington travelled far along the Atlantic coast, and in 1860 set up the first studio in Senegal; the following decade saw the birth of the first professional studios in Sierra Leone, by Francis W. Joaque, and in Gambia, by John Parkes Decker.

Portrait of five man (c. 1880–85), Lutterodt and Son Studio. Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Accra, the first pop-up studio was established in 1876 by George A.G. Lutterodt and his son Albert – about whom little is known, although they both found professional success, opening studios across the Atlantic coast from Accra to the Bight of Benin, teaching new photographers the tricks of the trade as they went. One photograph in the Met’s collection shows an unidentified Ghanaian dignitary, seated in a wicker chair and dressed in an elaborately woven robe, draped around one shoulder like a toga, with a sunhat perched on his knee. He is surrounded by four attendants, three of them with robes tied at the waist, on whose feet sand is still visible – the art historian Erin Haney suggests that they had travelled to the Lutterodts’ studio specifically to seek the commission, bringing with them fly-whisks and other regalia. We do not know who these men are, or what the occasion for the photograph might have been, but the careful composition encourages us to speculate about the power dynamics within the group. Somewhat incongruously, the five appear in front of an artificial backdrop that shows a European-style interior.

Across West Africa, painted backdrops imported from overseas were a mainstay of portraits of the era and down to the post-war period. Perhaps less so in Francophone West Africa – Meïssa Gaye in Senegal, for instance, favoured chequered textiles to chime with his subjects’ dress – but one finds them all the same in the works of Daniel Attoumou Amicchia in the Ivory Coast around 1950. Barnor says that, in his early career, photographers would order their painted backdrop from a catalogue. It was like a signature – ‘no two photographers would use the same backdrop,’ he says. Barnor would hang it outside during working hours to advertise his services to passers-by. European interiors were still depicted in those days – ‘because,’ Barnor says, ‘the painters didn’t know what African homes were supposed to look like!’

Writing in the 1970s, the anthropologist Stephen Sprague – one of the first to take up the subject of photography in West Africa – suggested that among Yoruba communities in south-western Nigeria, the ‘traditional formal portrait’ was ‘a fusion of traditional Yoruba cultural and aesthetic values with 19th-century British attitudes toward the medium’; both cultures ‘placed great emphasis on tradition, proper conduct, and the identity and maintenance of one’s proper social position in society’. Moreover, ‘the sculptural massiveness and bilateral symmetry of the pose relates directly to the form of Yoruba sculpture’; Sprague points to the practice of Yoruba photographers taking twin portraits, assuming the function of the small ibeji sculptures that were previously carved to mark the arrival of twins, which in Yoruba tradition was an important spiritual omen. Though taken a century earlier, the group portrait by the Lutterodts – with the gleam of the figures’ rings, the prominent fly-whisks, and the careful arrangement of the attendants around the chief – suggests precisely this sort of ‘proper’ formality, one that is repeated in photographs across the region, and which these elaborate backdrops only underscore.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Alphonso Lisk-Carew photographed a group of initiates from the secret, all female Bundu society, who posed in traditional dress, creating a rare record of costume, coiffure, ornament and perhaps social relationships. But, as Paoletti has pointed out, photographers were not simply passive observers of the scene before them. The Met’s Visual Resource Archive includes several photographs by the Togolese photographer Alex Agbaglo Acolatse, an apprentice of the Lutterodts; among them are two self-portraits from the 1910s, in which he is wearing formal European clothes – a tuxedo in one image, a bowler hat and bow tie in another – and posing before wall hangings. In a group portrait of around the same time, Acolatse doesn’t hide the fact that the grand interior depicted in the backdrop is a fiction; he allows the crumbling wall behind the curtain to show through on the left-hand side. Portrait photographers of the period also began to capture a less regimented reality by taking the camera out of the studio. One anonymous photographer, active in Saint-Louis, Senegal, around 1920, took a series of photographs of subjects at home, their walls laden with rows upon rows of formal portraits of family members, the eyes of many generations peering out the frame.

Un Jeune Gentleman (1978), Malick Sidibé. Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris. Courtesy MAGNIN-A Gallery, Paris; © Malick Sidibé Estate

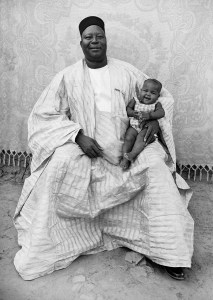

Untitled (1948–54), Seydou Keïta. Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art, Paris. Courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art; © Seydou Keïta/SKPEAC

Late in life, Seydou Keïta told André Magnin of Revue Noire, quite simply, that ‘I was capable of making someone look really good […] I always knew how to find the right position, and I never was wrong. Their head slightly turned, a serious face, the position of the hands.’ Keïta set up his first studio in Bamako in 1948, having recently purchased a large-format camera; in his photographs over the course of the next decade, his subjects pose before swirling arabesque backdrops or crumbling walls, dressed in suits or traditional robes, sometimes appearing with motorcycles or accordions. The results are always both monumental and modern; take, for example, a man in billowing robes, rendered massive by a close crop, holding a tiny chuckling infant to his side. It is reminiscent of a work by Barnor from the Ever Young days, of a mother held in rigid pose, but the ephemeral glimmer of a smile flashing across the face of the baby to her right (behind them is Barnor’s ‘signature’ of those early days, a painted European drawing room, complete with dresser and Ionic column). The photographs of Malick Sidibé, who was 14 years younger than Keïta, also flirt knowingly with the established conventions of portrait photography; known as the ‘eye of Bamako’, Sidibé depicted nightlife and jaunts to the seaside with his Rolleiflex, and in the studio the new stylishness of the post-colonial moment; Un Jeune Gentleman (1978) in flares and high-heeled boots, posing with one boot planted nonchalantly on a high stool (see cover). In a series of portraits taken the previous year, three yéyés in wide bell-bottoms stand before a painted backdrop – though now it shows a modern apartment block, opening on to a forest scene. The modernity of Sidibé, Keïta and Barnor does not break cleanly with the past, but builds on 19th-century traditions. And in the inward-looking, enigmatic self-portraits of Samuel Fosso from Cameroon, or the vivid colour portraits of Omar Victor Diop from Senegal, contemporary photographers continue to put their own stamp on the form.

With regret, Barnor tells me that he never met Sidibé – he found out about his work only later in life. But one suspects they would have had many notes to compare about these early days. That Barnor is so evangelical about his early studio work comes as something of a surprise, given that his fame was established on the basis of photoessays for the Daily Graphic, and his later shooting of the likes of Muhammad Ali for Drum. But the slow process of wet-plate photography, he says, taught him important lessons of how to ‘get the very best out of the materials I had to hand’ – ones he later applied to his work in colour in the 1970s; he explains how, in the 1940s, they would achieve the enlargement of a negative without a purpose-built enlarger. His knowledge of these methods is an integral part of what he calls his ‘archive’, his legacy. ‘I want the young people to know exactly how we dinosaurs did it,’ Barnor says. ‘I’m the connection between the dinosaurs and the present day.’

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.