From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Anyone picking up James Delbourgo’s book may be forgiven for thinking that this is a book about art. Or the human impulse to surround oneself with beautiful or resonant objects. It is neither of those things. Its purpose, the author tells us, is to explore an enduring cultural idea, namely that collecting is a sign of madness; that there is something peculiar about people who love things too much. To understand how we came to see the collector as a troubled person, he explains, we have to understand how we came to believe that when we look at a collection, we look at a self. It is an intriguing premise for a book.

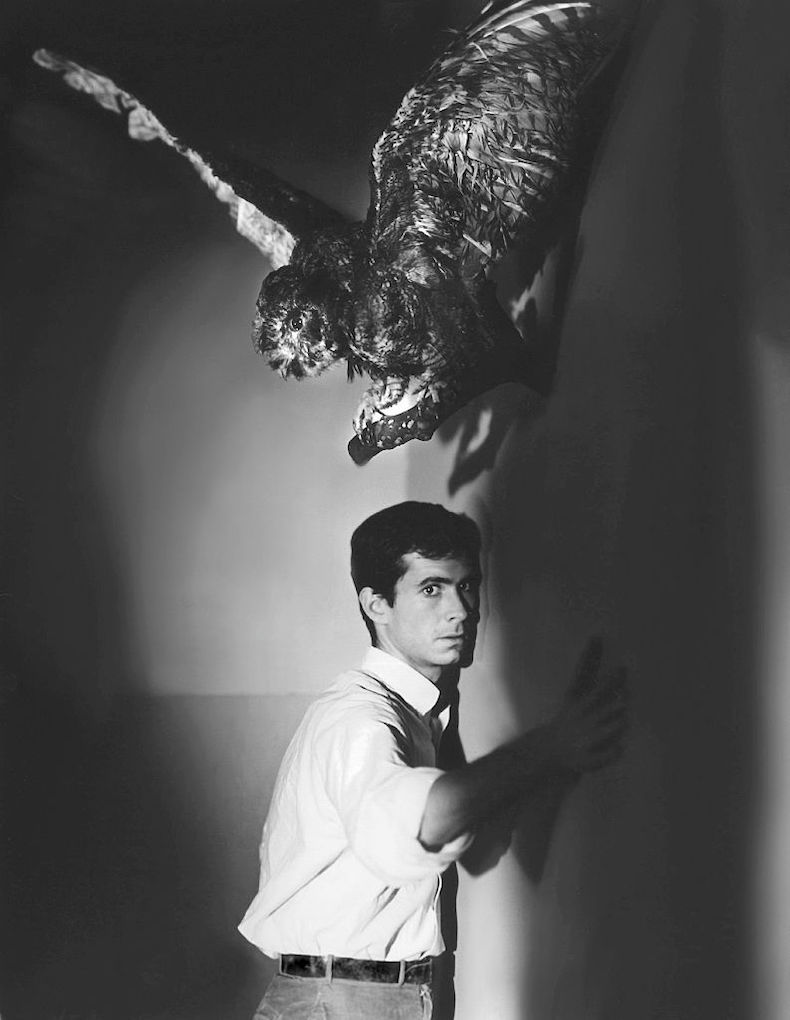

While not unduly concerned with specific artefacts, Delbourgo does offer ‘a grand portrait gallery’. Therein hang sketches of those fanatics, real and fictional, whose excessive acquisitiveness reflects the changing perceptions of the collector over time. Yet the author also plays to the gallery. It is no coincidence that this book opens with Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Norman Bates, or recognises that evil has always been more fascinating than good.

Certainly, Cicero found no good (and a great deal of perversion) in Gaius Verres, the governor and plunderer of Sicily in the first century BC. Verres extorted, terrorised and assaulted the island’s population and ransacked Greek temples, commanding the fleet to haul his loot – statues, art, gold and silver – back to Rome for a brazen display of luxury in his house. Cicero’s description of Verres’s amentiam singularem et furorem – singular and furious madness – is held up as a beginning of the idea that collecting, madness and sexual desire are linked. Alongside lust for art in the classical world there was also Statue Love, the title of the first chapter here, and both endured – as the defiling of ancient sculpture with lipstick as well as semen bears unpleasant witness. The British sexologist Havelock Ellis coined the term Pygmalionism for this affliction; as if to emphasise the point, the dust jacket of this book is given to Gérôme’s Pygmalion and Galatea, inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which the statue of Galatea turns to living flesh when kissed.

In the ancient world, the pillaging of sacred sites was considered an affront to the gods; the collecting of art associated with the tyrant. In the medieval and modern period, in Asian and Islamic as well as European cultures, the accusing finger pointed instead to the collector as idolator. Despite misgivings about material possessions, however, commentators in Ming dynasty China appear to have been the first to find virtue in the obsessive collector; these noble souls were suffering from a distinguished affliction known as pǐ, lauded because it inspired self-sacrifice and an authenticity of self.

Delbourgo’s handbrake turns take us next to 16th-century Prague and the court of Rudolf II, that most voracious and notorious of collectors. Magus as well as natural philosopher, he was as profoundly curious about progressive empirical science as alchemy and the esoteric writings of the Christian Kabbalah. His collecting of every conceivable kind of specimen, natural and man-made, may be seen as an attempt to assemble the world in microcosm in order to penetrate its secrets. The ambition of the later collector-naturalists was to impose order itself. Needless to say, such an eccentric ruler as Rudolf was seen by some as in league with the devil, like Christopher Marlowe’s anti-hero in Doctor Faustus, a melancholic who loses his soul in pursuit of knowledge and power. This notion of the collector as gloomy and reclusive cast another long shadow.

The British collector William Beckford is placed among the ‘Libertines and Trinket Queens’; Christina of Sweden, Marie Antoinette, Catherine the Great and Imelda Marcos are cited among the avid collectors accused of pursuing their own pleasure at the expense of their subjects. Bibliomania or book madness is exemplified in the person of the misanthropic Sir Thomas Phillipps, Romantic antiquarianism by the idiosyncratic Charles Kirkpatrick Sharpe, while Alexander von Humboldt is the quintessential Romantic explorer, combining heroic action with natural philosophy and poetic sensibility. As for Balzac’s eponymous hero in Cousin Pons, he represents the sad but sympathetic stereotype of the consummate collector-loser looking to find solace in his beloved treasures (which were not the ‘almost 2,000 Old Masters’ quoted here). The Picture of Dorian Gray is cast as another step towards the dominant image of the collector in the 20th century: a ‘“creepy” closet homosexual and sociopath’.

And so Delbourgo’s pacy narrative weaves through an age of ambivalence about the plundering of habitats, cultures and monuments to fill the universal, encyclopaedic museum, or the denuding of the great houses of a decadent Europe to adorn the homes of the American ‘squillionaire’. In revolutionary China and Russia, the collector becomes an enemy of the people – as he was in France and Germany, if he happened to be Jewish. In Communist Czechoslovakia, Bruce Chatwin’s fictional Utz lives through his collection, saving his soul by destroying the porcelain before it falls into the hands of the totalitarian state. We end with the total democratisation of collecting but also of the collectible. Nothing is deemed unworthy of accumulating these days, and HD – hoarding disorder – has become a recognised medical condition.

The cultural and historical range of A Noble Madness is impressive. Delbourgo charges down countless rabbit holes, the peculiar charm of this discursive book, although for all its compass there is a sense that much of his manuscript has been cut. Unfamiliar collectors and collections are ripe for discovery, as disparate as David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles and ch’aekkǒri, paintings of ‘books and things’ – Korean cabinets of curiosities conceived as self-portraits. Inevitably, Delbourgo paints with a broad brush and his sweeping statements do not always bear close scrutiny, but anyone more disposed than this reader to consider Noah, Don Giovanni and Norman Bates as collectors will relish this book.

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.