From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I have never seen James Ensor’s The Great Judge (1898) in person. Like many of my favourite images, it exists in a much-thumbed book and on a postcard that has been tacked to various walls. I summon the painting to my computer screen. Enlarge it until the colours dissolve into pixels.

The painting is housed in a private collection. It is less than a metre wide but the exuberance of The Great Judge’s colour and composition renders the canvas larger in my imagination. I know it is painted in oil but cannot discern the brush strokes. I am a distant and intimate viewer. The Great Judge is in part a work of my imagination, but it is all and uniquely James Ensor. I could never have made it up.

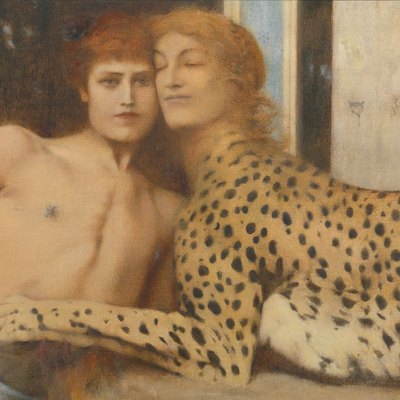

The judge is at the centre of the painting wearing a crushed, black toque. His empty eye sockets stare at the viewer. He holds a set of scales lopsidedly in his left hand. His right hand grasps the neck of a figure wearing what may be a Noh mask, though it has eyebrows and white teeth. The mask appears to be screaming in pain or despair. You can never be sure with masks.

The judge is draped in a white robe: perhaps his shroud. The figure he is gripping wears a calamine pink confection banded at the waist and sleeves with baby blue – or is it the palest of pale lilacs? The judge and his victim are flanked by masked grotesques, including a Pierrot whose disguise sits awkward and too large on his lumpy body. We cannot be certain of the genders of these figures, but fancy hats and collars suggest that some may be women.

The colours of the painting are gorgeous. Crimson, indigo and Easter yellow shine among muddied browns, whites and liverish grey. The blue-indigo background might be a stage curtain that can be drawn back to unveil the real world. Masks and costumes can also be removed. Yet there is no suggestion that the faces beneath the disguises are any less terrible. This is the theatre of The Great Judge: a dreadful courthouse. The fashionable hats and presence of the Pierrot suggest that it is also a place of entertainment.

James Ensor lived for most of his life above his mother’s bric-a-brac shop in Rue-de-Flandres, Ostend, a small town on the Belgian coast famous for its carnivals. The art critic E.M. Benson, an early advocate for the artist’s work, visited Ensor’s fourth-floor apartment in the early 1930s and described some of its contents:

Japanese masks, tall carved chests, bowls of fish, shells worked into ink stands: skulls wearing wide brimmed hats, with cigars between their toothless jaws, worn rugs with crazy floral patterns, an old harmonium on which he often extemporizes, a vermillion ball of crystal hanging from the ceiling and reflecting disordered forms: Chinese vases over the painted marble fireplace, women’s shoes filled with faded flowers…

Masks, skulls, costumery, fake flowers and other carnival baubles, all of which were sold and displayed in his mother’s shop, appear throughout Ensor’s work. Weird revellers, dressed for a cavalcade, reoccur in his paintings. Judges often feature. Justice is traditionally depicted as a virtue who wears a blindfold to stop her from being distracted by fear or favour (though we suspect she occasionally peeks). Ensor’s Great Judge has no eyes, but can we be certain he does not see? He represents death, after which, according to various religions, earthly actions will be weighed by the highest power, but Ensor’s gurning skeleton lacks a full set of teeth. He looks furious, rather than wise.

Like many European artists of the period, Ensor was drawn towards anarchism. His protest took the form of art rather than the bullet or the bomb. He was a founding member of the avant-garde group Les XX, dedicated to challenging the official Salon which they considered overly conservative and bureaucratic.

The Great Judge conveys Ensor’s contempt for bourgeois hypocrisy. The judge and his merry crew are ridiculous. There is an edge of anger in the painting. There is also an edge of hilarity. The tension between these two elements, rage and comedy seems to have co-existed in Ensor the man. A curmudgeon with a childish, often scatological sense of humour. Piss, ordure and decay are gleefully employed in his compositions. When Ensor became alienated from Les XX, he painted a mammoth carnival at the back of which revellers defecated on Les XX insignia.

The Great Judge instils another emotion: fear. As Lon Chaney once noted, ‘Nobody likes a clown after midnight’. Two decades before Sigmund Freud’s essay on ‘The Uncanny’ discussed the creeping dread aroused by certain dolls, stolen eyes, death and the inanimate made animate, James Ensor painted it in oils. The skeleton judge, the Pierrot and laughing masks are frightening. When we look on The Great Judge, we know we are mortal.

The Great Judge (1898), James Ensor. Photo: akg-images

Louise Welsh’s tenth novel, Nature of Dogs, will be published by Canongate next spring.

From the June 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.