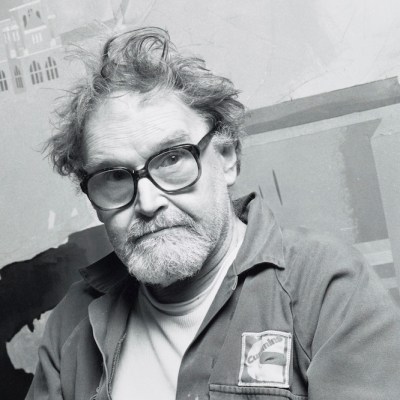

‘I believe then, as I believe now, that life and condition of people can be implied by a sensitive realist response to the places in which they live and work,’ James Morrison (1932–2020) wrote in 1977. He was referring to the paintings of Glasgow tenements that made his name as a young artist, in which he refused to include human beings in spite of pleas from influential quarters.

Morrison had left Glasgow, where his father had worked in the shipyards and where he had studied at the art school, in 1959. He moved first to the fishing village of Catterline, Aberdeenshire, where he was a neighbour and friend of Joan Eardley. Here he produced detailed depictions of fishing vessels, returning to his native city in order to practice his technique on the subject matter he knew best. He later settled in Montrose (within commuting distance of a teaching post at Dundee’s Duncan of Jordanstone art school), where he remained until his death. His trips to Glasgow became increasingly rare, and he became known exclusively as a painter of rural and coastal landscapes. Yet this exhibition at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh suggests that Morrison’s eschewal of manmade subject matter was in fact a quest to find man’s place within a natural world he battled to comprehend.

This may come as a surprise to anyone who first encountered Morrison in the documentary Eye of the Storm (2021), in which the painter offhandedly remarks that ‘the people seem a kind of irrelevance to what the landscape is to me.’ But in displaying works from across six decades of the artist’s career, the current exhibition reminds us that Morrison displayed not just range but significant continuity of message as well as subject.

Caledonia Road Church (1977), James Morrison. Courtesy The Scottish Gallery; © Estate of James Morrison

The 110 works on display (and for sale) at Scotland’s oldest commercial gallery begins with Morrison’s early paintings of Glasgow tenements, although only the mammoth canvas Glasgow Tenements (1960) is included here. Morrison attributed his embrace of ‘socially relevant’ painting in the 1950s and ’60s to his friendship with Glasgow painters including George McGavin and Bill McLucas. He would later cite the influence of the Hague School and that of Claude Lorrain, whose mark can be seen in the colonnade depicted in Caledonia Road Church, Glasgow (1977).

The downstairs rooms progress through Morrison’s depictions of fishing boats in Catterline and the Angus landscapes for which he had become well known by the mid 1980s, when an exclusive contract with the gallery allowed him to give up teaching at Duncan of Jordanstone and focus entirely on his own work. Upstairs, a bust of the artist’s head sculpted by his friend David Miller faces directly on to Beech Tree, Montreathmont (1981), an oil painting on circular board featuring Morrison’s characteristic wispy branches. But unlike its gallery neighbour, Glenesk Wood (1997), in which the trees seem to reach out to one another, Morrison’s beech tree is set apart from the trees in the forest behind it, corresponding instead with the viewer – and, in this case, Miller’s bust. It seems odd that Beech Tree, Montreathmont is rather haughtily framed and covered – caged, even – in glass, while other boards are left exposed: the glass restrains the tree from the interaction that Morrison’s painting invites.

Beech Tree, Montreathmont (1981), James Morrison. Courtesy The Scottish Gallery; © Estate of James Morrison

After seeing Morrison’s paintings of Assynt in Scotland’s far north, Arctic biologist Dr Jean Balfour invited the artist to join her research party to the north Arctic in 1990. He was ‘totally enthralled’ by the landscape, and returned multiple times. ‘My intention was always to do in the far north what I had done at home, that is to paint the landscape before my subject and try to make sense of it,’ he later recalled. Morrison seems particularly successful in this intent in Iceberg Collage (1994). The iceberg is depicted across overlapping layers of board, but its shadow on the black ocean beneath is contrastingly flat, allowing the viewer to become an explorer by recreating the effect of the ice floating towards our gaze. Large Berg II, painted during the same expedition, captures an iceberg in a greater state of serenity. But it similarly emulates the artist’s experience of viewing the landscape: the division of the image into a 102 by 245cm diptych replicates the perspective of glasses or binoculars, the two boards fading into one view over time, while the glossy sheen of the foreground contrasts sharply with the pale shading of both sea and sky beyond the iceberg.

Iceberg Collage (1994), James Morrison. Courtesy The Scottish Gallery; © Estate of James Morrison

The exhibition also features a glass case containing a small selection of brushes and tubes of oil paint. ‘I have a very limited palette and haven’t changed that palette for a very long time,’ Morrison explains in an excerpt from an interview displayed alongside it. ‘When you’re painting outside you’re contending with wind, changing weather and bugs, so you need to keep it as simple and straightforward as possible.’

In front of the case is Black Landscape (1964), which shows a hilly landmass rendered in cadmium yellow and black; an almost apocalyptic marble effect of blurred, fiery rock. Yet our eyes are drawn to the horizon where the land meets a skyline of pallid green and grey. Here the land comes into high definition over a carved stone arch: likely a drift into abstraction, but a subtler kind than in, for example, Field Boundary (1965), which Morrison’s friend and colleague David McClure described as a ‘calligraphic’ imprint of ‘the mark of men on the lands of the Mearns’. Looking at Black Landscape, its stone gateway to the unknown seems not just a marker of another world, but an invitation to explore it with Morrison.

Black Landscape (1964), James Morrison. Courtesy the Scottish Gallery; © Estate of James Morrison

‘James Morrison (1932–2020): A Celebration’ is at the Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, until 25 June.