In Eye of the Storm, Anthony Baxter’s documentary portrait of the artist as an old man battling the decline of his eyesight, James Morrison (1932–2020) tells of the occasion when, in the 1950s, the head of the Glasgow Art Club wanted to include one of his austere grisaille depictions of Glasgow tenement buildings in an exhibition. ‘The Lord Provost has agreed to open the exhibition – this is a great honour to you James,’ he said. ‘But I’ve written to tell you that you could make one or two changes that might improve the painting.’ To the suggestion that Morrison bring his brushes and his palette to the club there and then, in order to turn his painting into a vignette with the addition of a small child riding a bike across the foreground, Morrison replied: ‘Under no circumstances.’

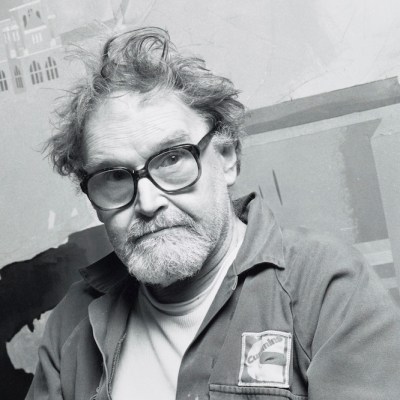

James Morrison in ‘Eye of the Storm’. © Eye of the Storm/Montrose Pictures

Self-effacing but strong-willed, eschewing what he described as ‘any sentiment or fakery’, ‘Jim’ Morrison always sought his own direction as a painter. Born in Glasgow, the son of a shipyard pipefitter, he studied at the Glasgow School of Art in 1950 under David Donaldson. Unimpressed with the vogue for abstraction and for political art, in 1959 he moved to Catterline, a small fishing village on the Aberdeenshire coast later made famous by Joan Eardley. Eardley was a close friend – but, as Morrison explained shortly after her death in 1963, ‘because she was such a powerful, powerful painter, I felt that if I had to develop myself as a painter then I had to keep, in a sense, her talent at arm’s length’. Like the Glasgow Boys before him, Morrison drew on the influence of Millet and the Barbizon school – but he was also drawn to Claude Lorrain, and to the heroic 19th-century landscapes of the Scotsman Horatio McCulloch. He says in the film that what he was looking for in the paintings of his predecessors was a kind of ‘rough truth’.

Approaching Storm, James Morrison. Photo: © James Morrison/Eye of the Storm

For Morrison, painting was both an ‘argument with himself’ and ‘an argument for himself’. He had a wonderful facility for skies and weather, and his seascapes of the east coast run the gamut from roiling fury to calm and quiet probing – revelations of a mental landscape as complex and dramatic as the wild places he depicted. In the 1990s, he accompanied an expedition to Nunavut, where he put up with freezing paints and fingers to depict the icebergs off Otto Fiord. ‘I don’t get as good conditions as this at home very often,’ he enthuses, in one of many pieces of compelling archival footage used by Baxter. He stopped painting briefly after the death of his wife Dorothy in 2006 but, encouraged by his son to ‘paint your agony’, Morrison then produced what he called a ‘portrait of grief’ – A Lady Remembered (2006), in which storm clouds coil together over a dark sea – which is likely to live long in the memory of anyone who sees it.

James Morrison painting in the Arctic. Photo: Estate of James Morrison

This film is a strong advertisement for the work of an artist who has long been well regarded in Scottish circles, but is little known beyond them. But by following the travails of a painter as he loses his sight, the film also strikes at something more universal – it is, in effect, an elegy for a sense. As touch comes to stand in for Morrison’s failing vision, the artist comes to take genuine pleasure in the feel of fresh white paper. The knowing petulance with which he grumbles that he’s no longer ‘allowed’ to paint outside, as he always has done, is countered by his appreciation for the gift of still being able to paint at all. In its sentimental way – intimate scenes of Morrison at home, interspersed with wide-angle shots of the Scottish landscape and set to a soundtrack of soaring Celtic strings by Karine Polwart – perhaps the film is Baxter’s own gentle ‘argument’ with the artist. For Morrison, ‘people seem an irrelevance to what the landscape is doing’ – but the film contends that the personality behind the paintings was anything but. It’s just such a shame that he never got to see it.

Bergs, Otto Fiord (c. 1992), James Morrison. Photo: © James Morrison/Eye of the Storm

Eye of the Storm (dir. Anthony Baxter) is available on BBC iPlayer.