When he’s not coaching Jack Draper, the current British #1 tennis player, James Trotman pursues a personal passion that is, to say the least, unusual in the world of competitive tennis: collecting abstract art. A former doubles champion who became a coach after a series of injuries drew an end to his promising career on the court, Trotman spends much of his downtime researching his favourite ‘post-war mod Brit’ painters, tracking down their work and assembling a collection that largely comprises work by women, though a few male artists – most notably Derek Jarman – feature prominently. He also has a growing collection of British studio ceramics, and counts Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie among his favourite potters.

Over the years, Trotman’s research has given him a respectable baseline of art historical knowledge. No longer reliant on the gallerists who used to court him when he was a novice in the art world, he frequently attends auctions to net paintings by his preferred 20th-century artists. While preparing for the US Open, which commenced in earnest yesterday, Trotman set aside some time to talk to Apollo about his long-standing love of modernist art, how he got to grips with the art world, and why art and tennis make for a natural match.

James Trotman, best known for coaching Jack Draper, the current British #1 tennis player, has been collecting art for around 15 years. Courtesy James Trotman

What is the artwork you first fell in love with?

I don’t remember a light-bulb moment as such, but it would’ve been something modernist. Even from a fairly young age, if I saw a Miró or a Picasso, it kind of got me more than a Constable, say. I’ve always travelled a lot for work, so when I did get some spare time, I would check out a museum or gallery. I didn’t really know much about art, and have no academic background as such, but I just always enjoyed it – getting away from what I did, as much as anything, and into a different environment.

I began collecting by chance, without really knowing anything about what I was doing. I just started following auctions of post-war modern British art at Bonhams and Christie’s, because I thought that was a decent place to start. I read a lot of books to understand what was going on. And then I started buying, and my tastes evolved and changed. I’ve been buying art now for around 15 years.

You collect mostly women artists. Why is that?

It’s a cliché that women artists have been under-appreciated for so long, but it’s true: there are still opportunities to buy great works by great artists whose stories haven’t been told fully. One of my favourite artists is Paule Vézelay: I own a lot of her works and try to buy what I can. I just feel that for what I’m able to pay and how great an artist she is, I can build a fantastic collection of her work on a lower budget than I could with the work of her male counterparts.

Thérèse Oulton is another artist who I think is incredible. You speak to many people in the art world and they’ll say, ‘I remember Thérèse, I went to her first show in the ’80s at Gimpel Fils, I saw her work at Marlborough Gallery, I was blown away.’ But hardly anyone talks about her work today. I buy her works at auction whenever they pop up, and I think, ‘I’m owning an incredible piece of art here, which I’m going to enjoy for years to come.’ The current price point just doesn’t make sense. I think it’s a myth that you have to spend huge amounts of money to build a great collection.

I have a lot of work by men, though, and still buy male artists.

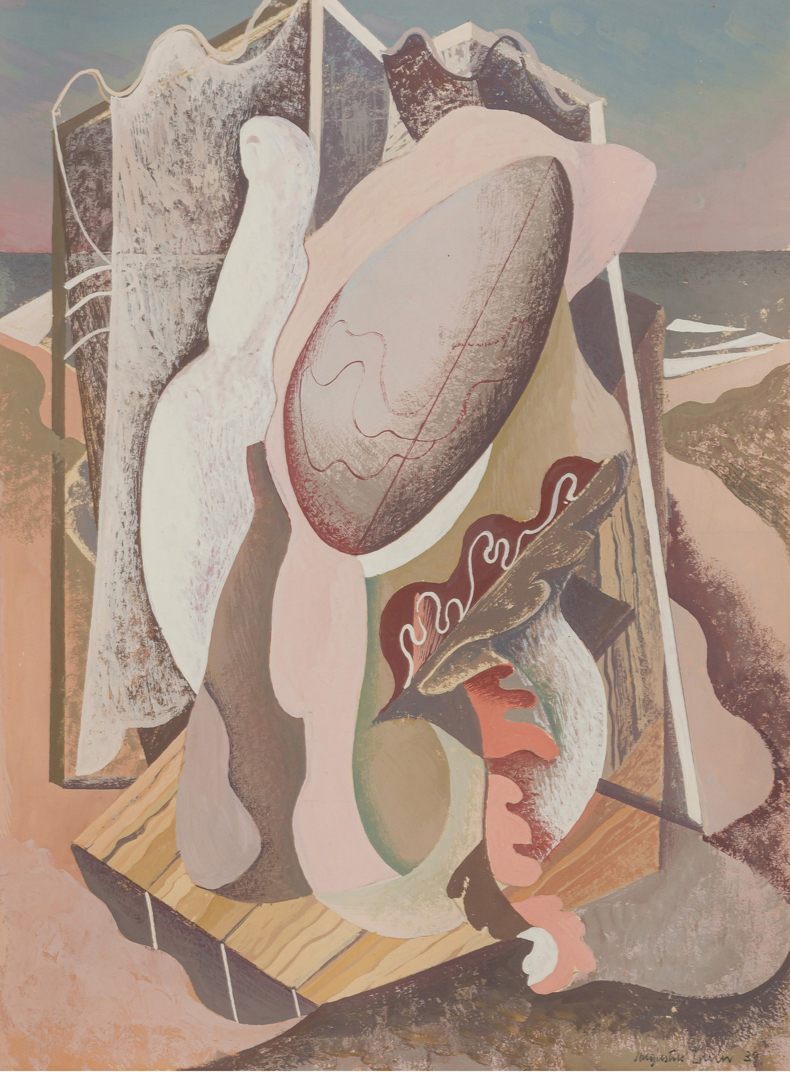

Surreal Composition (1939), Augustus Lunn. Collection of James Trotman; courtesy James Trotman

What is your overall approach to collecting?

My collection is a bit random; I would say it’s eclectic. There are some commonalities between the pieces, but there are also a lot of artists you wouldn’t necessarily think sit together.

I spend a lot of time watching auctions, and I’ve set up searches for assorted things: ‘abstract’, ‘Surrealist’, ‘1930s’, and out of every thousand items maybe one pops up that’s interesting. I recently bought an abstract painting by the British artist Sidney John Woods from 1937. There’s very little on him online. He went into graphic design, especially posters, but if you dig around you find that he was great friends with John Piper, who was making abstract paintings at a similar time. But I didn’t know anything about Woods; I just thought it was a good painting. In that inter-war period of British art, there wasn’t a lot of abstract art around. So I bought it partly for that reason.

Has the way you buy art changed over time?

There were certain galleries that I would buy works from, and I moved away from that – in the post-war mod Brit space I felt very pigeonholed, because they were pushing the same artists the whole time. I felt obliged to buy work by a certain artist – rather than looking for myself, I was led by what they were selling and the story behind it. And I kind of got bored, if I’m honest. So I try to remove myself from as much external influence as possible.

I buy a lot more at auction now. It’s just a natural progression. When you’re new to collecting and you see something through a dealer, you think it has some kind of stamp of approval; you think, ‘Oh, I should be buying this.’ But if I like the work, and it’s within the budget I had in mind for it, that’s the only thing that matters.

You’ve mentioned that your house has become a bit like a gallery. How do you curate it?

My wife and I rotate the works once or twice a year. We do it purely off image and whether we think works can sit well together in certain rooms. By rotating the works, you end up finding relationships between pictures that you hadn’t necessarily thought were there. But there’s no methodology as such. I can’t hang everything I’ve got, but I try to hang as much as possible.

What are some examples of pairings or hangings of paintings that have been unexpectedly pleasing to you?

The wall behind me right now is pretty nice – coincidentally, three works by women artists. In the middle is Angelus, a work by Inez Hoyton from the 1940s, when she was down in Penzance. That sits with a lovely little Paule Vézelay on the left, and on the right a work from the 1940s by another artist I love, Frances Richards, who did these incredible embroideries. This painting, titled Small Figure, is an oil on board, but I want to find one of her embroideries to add to my collection. She was married to Ceri Richards, who was much more renowned, but her works are stunning – really, really beautiful. That set of three works hasn’t changed for quite some time; they sit really well together.

Eight Curved Forms and Two Circles (1947), Paule Vézelay. Collection of James Trotman; courtesy James Trotman; © the estate of the artist

Are there any similarities between tennis and art?

Both are about getting in the zone. When painters are making a series of good works, they will find themselves in a certain headspace. Some works are more of a struggle, and though that doesn’t mean they’re going to be bad, there are those moments when things are easier and are happening on that subconscious level. It’s the same with tennis.

Also: take Nadal and Federer. The rules of the game are the same, and so is the equipment, but the results look very different. Nadal is very high-energy and intense, whereas Federer, with his smooth, flowing style, is almost the opposite, like a magician. It’s like two artists who look out at the landscape and capture it both completely differently. The artist’s individuality comes out in their style.

James Trotman watches as Jack Draper prepares for the French Open in 2023. Photo: Clive Brunskill/Getty Images