From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This month, the Czech film-maker and artist Jan Švankmajer, best known for his surreal, gruesome, disconcerting and, if you’re in the right frame of mind, startlingly funny and beautiful animations, turns 90. Over more than 50 years he has made more than 30 films, many of them no more than a few minutes long, seven of them full-length features, and has won a reputation that crosses all borders of language and genre. His influence has been acknowledged by film-makers as different as the Brothers Quay (whose contribution to the video for Peter Gabriel’s single ‘Sledgehammer’ of 1986 shows what an impression Švankmajer had made on them), Guillermo del Toro (Pan’s Labyrinth, 2006; The Shape of Water, 2017) and the animator Henry Selick (The Nightmare Before Christmas, 1993; Coraline, 2009). Apart from David Lynch, whom Švankmajer admires, no living film-maker has so successfully made a career founded in his personal neuroses and obsessions (which include puppets, dolls, stuffed animals, skeletons, insects, disembodied tongues, decaying flesh, rotting fruit, alchemy, the fiction of Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe and the court at Prague of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II), so indifferent to the demands of commerce. As well as films, he has created visual and ‘tactile’ art, theatre, book illustration and literature, refusing to admit boundaries between forms.

He was born in 1934 in Prague, not the calmest place to be growing up in the mid 20th century. In the 1950s he studied stage design at the city’s School of Applied Arts and then at the Academy of the Performing Arts, where he also took courses in the puppetry faculty: puppetry is an important tradition in Czechoslovakia – for a time under Habsburg rule, puppet theatre was the only Czech-language theatre allowed – and as a child Švankmajer had his own miniature puppet theatre. After graduation, he worked in puppet and mask theatre; it was while mounting his first production that he met Eva Dvořáková, who became his wife and artistic collaborator, designing most of his films until her death in 2005. His first film credit was as puppeteer in Johanes Doktor Faust (1958), a traditional version of the myth directed by Emil Radok, one of Švankmajer’s theatrical mentors. It was another six years before he directed his first film: in The Last Trick (1964), two figures in Victorian costume with giant puppet heads perform a series of tricks – Mr Edgar places a painted wooden fish inside his skull, winds himself up with a handle inserted into his earhole, and removes the fish’s skeleton, stripped clean; Mr Schwarzwald opens his head to reveal a violin, with which he accompanies a wooden dog as it dances… Virtuosity and undertones of aggression escalate with each new feat until, after 11 minutes, it ends in violence. The film might feel parodically avant-garde if it weren’t so confident, so resolute in establishing that all this is perfectly normal, even if it’s not a normal you’ve come across before – a trick of tone that Švankmajer has brought off time and time again.

The White Rabbit in Alice (1988) is also caught up in a sea of the heroine’s tears, but manages to escape. Image: Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo

Throughout the 1960s and into the early ’70s Švankmajer made a succession of short films using a bewildering variety of forms and techniques – perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he used a variety of bewildering techniques: 2D animation, 3D stop-motion animation, with puppets, people, and people disguised as puppets, sometimes several of these within a single film, milled together with rapid-fire editing. His films were shown at international festivals and won awards, but also the attention of the Czech communist authorities. In 1972, he made changes without authorisation to his short film Leonardo’s Diary, which combined in unpredictable ways animated versions of drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and archive film of 20th-century scenes. Half a century on, it seems one of his least alarming films, but perhaps in post-’68 Czechoslovakia the brief shot of riot police quelling disorder touched a nerve. Whatever the offence, he was required to rest from film-making, setting aside a partly completed short inspired by Horace Walpole’s Gothic novel The Castle of Otranto; he was finally permitted to finish it in 1979.

It was after this break that his career began to take off internationally. His extraordinary short animation Dimensions of Dialogue (1983) won a Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and the Grand Prix at the Annecy Animation Festival; in 2001 Terry Gilliam named it one of the ten best animated films of all time. (Another kind of accolade came its way when it was shown to the ideology commission of the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party as, Švankmajer says, ‘an example of what had to be avoided’.) The film consists of three episodes: animated Arcimboldo-like heads – made from food, from kitchen utensils, from school equipment – devour and vomit up one another; a clay man and a clay woman kiss, meld into a single mass of clay, separate, fight, meld again; a pair of clay heads extrude matching objects from their mouths (toothbrush, toothpaste; bread, butterknife), the exchanges becoming increasingly frantic and inappropriate (toothbrush, pencil sharpener; bread, shoelace) until the heads are left wrecked and gasping.

Installation view of ‘Disegno Interno – Eva Švankmajerová/Jan Švankmajer’, which ran at the Gallery of the Central Bohemian Region (GASK) from March–August this year. Photo: CTK/Alamy Stock Photo

Meanwhile, Švankmajer’s reputation began to make itself felt in Britain outside narrow cinephile circles: in 1984, an episode of the Channel 4 arts series Visions was devoted to him, which included the Quay Brothers’ animated homage, The Cabinet of Jan Švankmajer. After this, Channel 4’s production arm Film Four funded his first feature, Alice (1988), a very loose animated version of Alice in Wonderland (the Czech title, Něco z Alenky, translates literally as ‘Something from Alice’). It is more unsettling than Lewis Carroll’s original, or most adaptations – it seems to owe a good deal to Freud’s idea of the uncanny. Some of the animals Alice meets are stuffed, including the White Rabbit, who leaks sawdust from time to time; some of them have skulls for heads. The Mad Hatter is a carved wooden puppet, the March Hare a clockwork beast in a wheelchair. Alice herself, when she shrinks, becomes a slightly eerie doll. Švankmajer’s interest in Carroll was already clear: his short Jabberwocky (1971) took off – admittedly, in very idiosyncratic directions – from Carroll’s poem, and Down to the Cellar (1983), in which a young girl is dispatched underground to fetch potatoes from a storage bin, felt like a deliberate allusion to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Švankmajer’s Alice is attuned to Carroll’s logic and the violence that underlies the story (in this respect, it perhaps has a kinship to Jonathan Miller’s trippy BBC version of 1966), but eschews his decorum – the opening announcement that it is ‘A film made for children… perhaps’ should be taken as a warning. When Alice causes a flood with her tears, a mouse moors a boat to her head, jamming a stake in her scalp (ouch!) and cutting hair to burn as fuel to cook a meal. When the Queen of Hearts cries ‘Off with their heads’, the White Rabbit produces a pair of scissors and swiftly decapitates the Hatter and the Hare: the bodies grope around for their heads, and end up wearing the wrong ones. The film scooped the top prize at Annecy again and was an international critical success, particularly – to Švankmajer’s relief – in Britain, Carroll’s homeland.

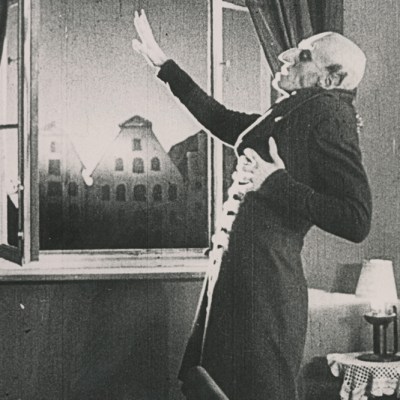

After this success and the subsequent collapse of communism in eastern Europe, the BBC jumped on the bandwagon, commissioning The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia (1990). This nine-minute epic, subtitled ‘A Work of Agitprop’, opens in 1945 with a plaster bust of the Czech communist leader Klement Gottwald being born by caesarian section from a plaster bust of Joseph Stalin, and ends in 1989 with a plaster bust of Stalin – now painted in the Czech national colours – giving birth to… At this point the screen goes blank. It is by turns aggressively unsubtle and difficult to parse. The BBC also commissioned Faust (1994), Švankmajer’s first large-scale film with actors, which jams Marlowe, Goethe, Gounod and Czech folk versions of the Faust myth together with a present-day narrative in which a man (the actor Petr Čepek) follows clues and portents around Prague, unlocking doors, finding himself in a theatre dressing-room, on stage expected to play Faust, in an alchemist’s laboratory where a baby homunculus comes to life in an alembic, conversing with puppet angels and demons, demonstrating his magic to the king of Portugal. The British video artist Ed Atkins, who has a major solo show at Tate Britain in 2025, has said that Faust is his favourite film, and ‘Pretty much everything I’ve ever made that’s of any merit has pilfered something from it.’ (The film is easiest to find in an English-language dubbed version in which all the voices are spoken, very brilliantly, by Andrew Sachs.)

Faust (1994), the first of Jan Švankmajer’s films to feature actors, fuses several versions of the Faust myth – and still has roles for some demonic puppets. Courtesy Everett Collection

Over the next couple of decades, feature films kept coming, but at longer and longer intervals. Little Otik (2000) – aside from Alice, the nearest Švankmajer has come to an international hit – is based on a Czech folk tale about a childless couple who adopt an oddly human-looking tree-stump. The stump baby comes to life but turns out to have an almost boundless appetite; and soon the neighbourhood is plagued by mysterious disappearances. Eva’s death slowed things still more. Two more films followed: in Surviving Life (2010) the protagonist is caught between marriages real and dreamed; the film itself is caught oddly between animation and live action. His final film, announced as such in advance, was crowdfunded – Guillermo del Toro was among film-makers who joined the appeal, calling Švankmajer one of the masters of Surrealism, which he defined as ‘undomesticated art’. In Insect (2018), absurd events overtake actors rehearsing Karel and Josef Čapek’s The Insect Play (first published in 1921) ; meanwhile, the camera keeps hopping to the other side of the fourth wall to show Švankmajer directing – a farewell glimpse.

Film is what Švankmajer is best known for, and he regards it as having advantages – one of them being that, as he has told the critic Peter Hames in 2006, unlike theatre ‘It can wait for its audience […] I became convinced of this when I was involved in the Theatre of Masks [the theatre company he formed in 1960]. People did not understand and left during the performance – whereas my films have waited 20 years for their audience.’ But he has never seen himself as only a film-maker, maintaining that creativity shouldn’t be bounded by forms. In ‘Decalogue’, an essay setting out his artistic principles, first published in 1999, his first commandment is ‘Remember there is only one form of “poetry” […] Before you start making a film, write a poem, paint a picture, create a collage, write a novel, essay etc.’ When he was unable to make his own films in the 1970s, he created animations and special effects for fellow film-makers, wrote poetry and made three-dimensional ‘tactile art’; he also produced a book about this last subject, Touching and Imagining (2014), which has been translated into several languages, including English. Švankmajer argues that touch is the most neglected of the senses within the arts; and it is striking how often in his films the textures of things (close-ups of pieces of cloth, crumbling stone, flaking paint and plaster, clay, mud) leave a strong impression. During the hiatus, he and Eva started making bizarre ceramics together, under the name E.J. (sometimes J.E.) Kostelec – the surname taken from Eva’s hometown. In the early 1980s, the couple bought a dilapidated castle in the Bohemian forests, at Horní Staňkov, which they transformed over the years into a Wunderkammer, filled with their pottery and puppets alongside found objects and Indigenous art from Africa and the Pacific.

In Little Otik (2000), a childless couple adopt a tree stump and come to regret their decision after it develops an insatiable and murderous appetite. Courtesy Everett Collection

The thread connecting all the Švankmajers’ artistic activities is Surrealism, a label often slapped on artists quite casually, regardless of their own preferences, but one that Jan proudly claims. They officially joined the Czech Surrealist group in 1970 – before then, Jan’s work was more obviously influenced by the Mannerism of the late Renaissance, with its rejection of naturalism and emphasis on the virtuosic and grotesque, which reached its apogee in Rudolf II’s court at Prague. That heritage is clear in the short film Historia Naturae, Suita (1967), in which stuffed animals, eggs, skeletons and early zoological engravings are animated into a kind of dancing cabinet of curiosities, but it’s also there in the Arcimboldo heads of Dimensions of Dialogue and the flower woman of the extremely short film Flora (1989).

To be a Surrealist in Prague is quite different from being a Surrealist in Paris or Brussels. As Švankmajer has explained it, whereas Western European Surrealism has its roots in Dada, with its embrace of the absurd, Czech Surrealism sprang from the ‘poetism’ of the writer and artist Karel Teige. Teige was all for civilisation and technology, but believed that humanity also needed a dose of the bizarre, a release from reason – ‘An eccentric carnival, a harlequinade of emotions and ideas’. Traces of Western Surrealism can be found in his films, though – notably The Flat (1968), in which, in a shot straight out of Magritte, a man looking in a mirror sees the back of his own head.

Surviving Life (2010) combines live action and animation, and follows a married protagonist who leads a double life in his imagination. Courtesy Everett Collection

Švankmajer has complained that for too many artists Surrealism is an aesthetic choice, whereas for him, it has a deeper purpose: ‘to change the world… and to change life’. Surrealism is inextricable from politics: it’s notable that he and Eva joined the Surrealists in the aftermath of the Prague Spring. Surrealism was a form of protest against repression. The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia is Švankmajer’s only explicitly political film, but the director himself has said that all his work is politically engaged. It is hard to ignore the undertones in films such as ‘Whip’, the second of three very short episodes in his animation Et Cetera (1966), in which a cartoon man whips a cartoon animal – something between a dog and a dragon – to make it perform tricks: little by little, as he cracks the whip, the man becomes more beastlike, the beast more human, until they have changed places. Or take The Garden (1968), his first film to feature human protagonists, in which a man visiting a country house is startled to find that the garden fence is made from people, standing docilely in line; the film ends with the visitor joining the fence himself.

At the core of Švankmajerian Surrealism is the act of dreaming – in ‘Decalogue’ he exhorts the artist to ‘Keep exchanging dreams for reality and vice versa.’ Watching films is compared often enough to dreaming, and plenty of film-makers try to capture the atmosphere of a dream, but it’s hard to think of many who manage it as persuasively as Švankmajer: Jean Vigo, perhaps, in L’Atalante (1934) and, among contemporary directors, David Lynch (again), in films such as Lost Highway (1997). What you feel strongly watching Faust and Surviving Life is the odd, chilling logic of dreams, in which cause and effect are replaced by a simple, natural inevitability: characters act as they are compelled to; things happen as they must. Another of Švankmajer’s commandments reads: ‘Imagination is subversive, because it puts the possible against the real. That’s why you should always use your wildest imagination.’ In the world of Jan Švankmajer, over and over again things happen as they never have before, as they never could, as nobody else could have imagined them.

In Lunacy (2005), based on two short stories by Edgar Allan Poe, Jan Tříska plays a depraved de Sade-like aristocrat known as the Marquis. Photo: AJ Pics/Alamy Stock Photo

Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films DVD box-set is available now.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.