From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

A short walk from where I grew up in Southampton, in the 1990s, there was a piece of graffiti in big capital letters along a red brick wall, by a main road. It read ‘LONG LIVE DUBČEK’. It must have been painted 30 years earlier in 1968, when the leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia attempted a ‘socialism with a human face’, only to be overthrown by Soviet tanks. Thousands of refugees fled the country. Among them was the teenage Jan Žalud, who is responsible for Head with Cheeks and Hair (Collection Box), an artwork from 1986 that is my favourite object in the city’s municipal art gallery.

Southampton is one of those English places, like Luton, Leicester, Portsmouth or Plymouth, that are both extremely mundane and an ongoing experiment in multiculturalism and modernity. The two notable things to happen to my hometown in the 20th century – aside from its centre being flattened in one night in November 1940 – have been mass migration and municipal socialism. The latter was expressed through a progressive housing programme between the 1930s and the ’80s and, more subtly, through the commissioning policies of its City Art Gallery, which since the interwar years has built an eccentric and rich collection of modern art.

Immigration is not a new phenomenon in Southampton – it has, like most ports, always been a city of migrants, whether Basque refugees from Franco’s bombings in 1937 or the Jewish and Afro-Caribbean ancestors of 2000s UK garage star Craig David. But one of Southampton’s particular distinctions is in how Central-Eastern European it is. Starting with the migration of displaced Poles in the 1940s, it has one of the largest Polish populations in the UK outside of London, with many Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Romanians and Bulgarians alongside them.

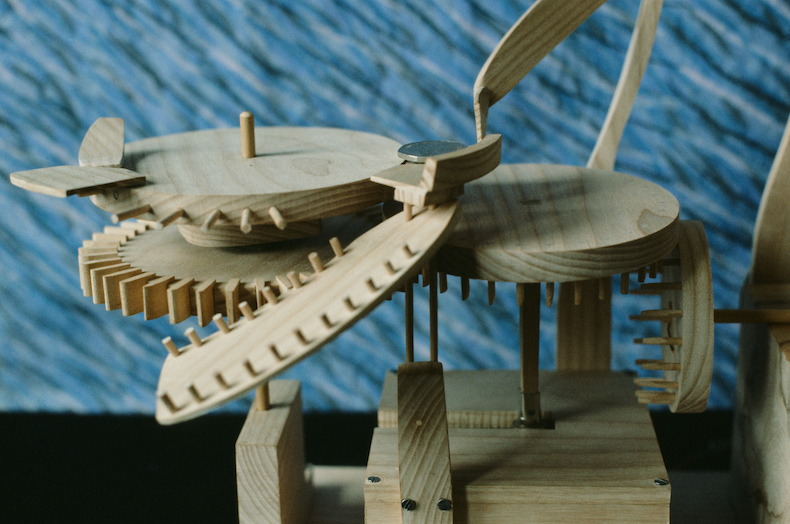

Žalud didn’t study art in his native Prague, but at a polytechnic in Sunderland. Yet his carved wood sculptures feel incredibly Czech, strongly of a piece with the great tradition of Surrealist animation in Czechoslovakia after the Second World War: think of the puppets of Jiří Trnka, or the satires in clay of Jan Švankmajer. Much of Žalud’s sculpture has taken the form of automatons – objects that, after a lever is pulled, acquire an uncanny ‘life’. In Head with Cheeks and Hair (Collection Box), a single wooden head is enclosed within a glass box, connected to a complicated, Duchampian system of cranks. You trigger it by inserting some loose change, which starts the cranks grinding. When you do so, the head reacts with grotesque excitement – its grins obscenely, its tongue pops out, its eyes roll, its quiff flutters.

As an artwork, Head is an endlessly enjoyable Surrealist object – every time I’ve visited Southampton City Art Gallery (a few times a year, for as long as I can remember), I stop at this little box, standing unobtrusively beneath a 1930s stripped classical vault, and throw a few coins in. It’s both a fascinating artwork in its own right and an elaborate joke about what it means to have a gallery like this in a very ordinary, working city. When I was growing up, the local press would lament the gallery’s every purchase, with the acquisition of a Bridget Riley painting especially scandalous; in a brief Conservative administration, the city attempted to sell off its most valuable paintings in order to fill its funding gaps. Every 10p piece helps.

The abundance and generosity of the welfare state era in this city is long gone, with the architect-designed council estates, glassy new schools and sports centres and the newly opened parks all a distant memory, a matter of modernist nostalgia; the port is sold off, the estates severely dilapidated, the centre colonised and disfigured by a series of interchangeable indoor malls. What does survive and thrive, though, is Southampton as a migrant city and one of its smallest but, for me, most moving monuments is this sharply ironic but joyful little wooden box.

From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.