In 1968, Janet Dawson was one of 40 artists – and only three women – selected for ‘The Field’, a landmark exhibition of colour field painting and hard-edged abstraction at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. It made the name of several Australian painters who went on to be recognised for their abstract or conceptual work. But over the course of her career Dawson moved away from the avant-garde and took up a figurative approach, making detailed paintings of homegrown vegetables and romantic studies of the moon. The retrospective ‘Far Away, So Close’, which covers more than six decades of Dawson’s shape-shifting practice, is compelling not only because of the immense range of work on display, but also as a record of her grand indifference to playing the art-world game.

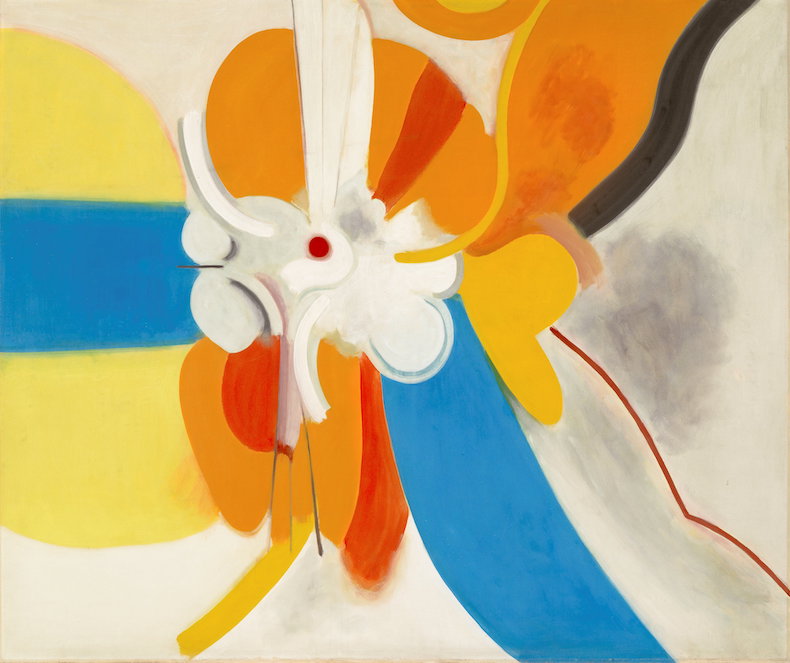

Dawson, now 90, was a precocious and hothoused youth. When she was six, her mother booked an appointment with the director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales to discuss her artistic future. Dawson began taking private art tuition at the age of 11 and later attended art school in Melbourne before travelling to Italy on an art scholarship. It was at this point, working alone for the first time, that she began to think about abstraction. These early experiments are polite; Cross to Oval (1960) and Circle and black bar (1961) show Dawson looking for harmonious compositions and a balance of tensions. From there, works such as The origin of the Milky Way (1964) grow bolder with colour, using a clear central point to create an exploding sense of energy and vitality.

The two works that appeared in ‘The Field’ show how Dawson continued to think about how energy flowed through the world and across the canvas. The accordion folds of Rollascape 2 (1968) suggest the play of light on physical forms, while Wall (1968) didn’t exactly hide its reference to the built environment. Dawson destroyed this work and recreated it on canvas and it’s this version, Wall II (1968–69), that appears in ‘Far Away, So Close’. With its taut, powerful line work, this large painting feels remarkably contemporary.

Dawson’s reputation as an abstract painter and printmaker seemed assured after ‘The Field’ but she soon began to incorporate elements of the natural world in her work, as in Ripple 3 (1970). Some years later she reflected, ‘Well, what is abstraction? It’s not a person, it’s not a country, it’s not a friend… abstraction is way of making a painting so why shouldn’t I betray it. I mean, it’s nothing!’ There are some 80 paintings, prints and drawings in ‘Far Away, So Close’ and they could easily feel like the work of several different artists, but Dawson’s enduring interest in the natural world provides a sense of continuity.

The retrospective frames Dawson as a rule-breaker and iconoclast, which is true in more ways than one. In 1974, she moved to Binalong in rural New South Wales with her husband. The Australian art world revolves around Sydney and Melbourne and there’s a tendency to equate rural with irrelevant. Dawson, however, had a clear sense of her practice, and has talked about wanting to ‘live as a working creature’. The exhibition includes photos of life on their farm at Scribble Rock as well as artefacts of other projects such as local community newsletters. It was a different definition of what a serious artist might look like.

Dawson lived at Binalong for the next 40 years and it shaped her practice. The works from the 1970s are abstracted landscapes. Some include energetic vertical lines reaching like trees. Old cloudy moons 1 and 2 (1979) is a geometric composition with the pearly luminosity of a winter’s night. These investigations eventually gave way to more traditional landscapes, although Dawson continued to study light and the moon in particular, as in the small, brooding pastel-on-paper work Morning Star (1993) and the tondo Moon at dawn through a telescope, January 2000 (2000).

In these later works, Dawson captures moments where the vastness of life feels intimate. They are acts of close observation. Her still lifes are just as attentive, but also show a worker’s pragmatism. Scribble Rock cauliflower (1993–97) considers a giant homegrown cauliflower in a plastic bucket. Kookaburra (1999) is a compassionate, unsettling study of the colours and textures of a dead bird; another small pastel drawing depicts sheep bones scattered over a bright yellow phone directory.

Dawson continued to exhibit but the curatorial attention she received was inconsistent, and her figurative work often felt out of step with the contemporary market. The 50th anniversary of ‘The Field’ brought her fresh accolades. Her work was included in significant exhibitions of Australian abstraction at the National Gallery of Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria and, in 2020, in the NGA’s major exhibition of women artists, ‘Know My Name’. The retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales is the first major state gallery exhibition to fit all the pieces of her practice together. Though it refrains from any overt feminist framing of how Dawson blended her art-making and her rural domestic life, it is refreshing to see her career considered in full.

‘Janet Dawson: Far Away, So Close’ is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, until 18 January 2026.