From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘I am nothing – “another” speaks in me,’ declared Jean Cocteau in a Paris Review interview published in 1964, just a few months after his death. ‘The Juggler’s Revenge’, at the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice, illustrates the accuracy of his self-assessment: his imagination resembled a hall of mirrors, an infinite machine of collage and juxtaposition. The photograph on the cover of the catalogue depicts the artist as a six-armed figure holding a book, a fountain pen, a pair of scissors, a cigarette, a paintbrush, while one hand rests upturned at his waist as if awaiting his next task. Cocteau was a polymath, a protean conjurer of worlds, a juggler – and, if the curators are correct, this exhibition offers revenge on all the critics who called him a dilettante. Despite his near-Warholian embrace of surface, celebrity and everything new (‘I myself do not’ read anything serious, he said in the same interview), he inhabited a world of ancient myth and melodrama, creating a friendly environment for both his sexuality and his desire to identify as a poet.

The films of this restless maker were poésie cinématographique, his drawings poésie graphique. And what a beautiful hand he possessed. Profiles, penises or the dome of La Salute in Venice – Cocteau could bring anything to life in unerring curls and swerves. Portrait of Raymond Radiguet (1923) is alive with a delicacy of touch: the young writer (he was 20 and would die that year) with small, sensuous lips, looks down at his hand, knuckles gently pinching a cigarette. In his Mandrake series (1936), Erotic Scene (1937–39) and Sailor Couple (1947) the drawings are marked by a mix of classical poise and uninhibited eroticism. As a colourist – even as a painter – he was tin-eyed. Oedipus, or, The Crossing of Three Roads (1951), has a cartoonish goofiness, its hues sickly and unharmonious, like some outtake from The Simpsons.

Oedipus, or, the Crossing of Three Roads (1951), Jean Cocteau. Private Collection. © Jean Clement Eugene Mar Cocteau, by SIAE 2024

At the age of almost 70, he drew a Sphinx (1958) as a creature afflicted by desire. Recalling the polymorphic sensuality of his Mandrake drawings, her head looks like a sentient mass of genitalia, with two eyes extending like penises, its bulging jaw a scrotum. The sphinx (she also appears in Testament of Orpheus, 1960, Cocteau’s final film) puffs out her chest, her breasts like cathedral domes, and even her anus, revealed as she lifts her tail, participates – its dark, circular form indistinguishable from the penis-eyeballs on her head. The faint outline of a Greek temple in the background and an asterisked signature complete the image: classical culture, life as a hermaphroditic riddle, and the artist’s name, all delineated with a sense of exquisite fun.

Despite Cocteau’s flair as a draughtsman, most of the drawings come across as playful ephemera that punctuated his life as a storyteller. Cocteau was a magnificent thief, adapting old stories and ideas – the poet doesn’t invent but listen, he said. Yet as a film-maker he was supremely inventive, with scenes from The Blood of a Poet (1930), such as when the poet splashes through the surface of a mirror, enduringly sublime. The ascension in Beauty and the Beast (1946), or Orpheus penetrating a mirror to enter the underworld (Orpheus, 1950) – these are beautifully rendered moments that honour the tone of the myths while taking up with ardent glee the latest tricks offered by modernity. The exhibition, above all, provoked in me a desire to rewatch all of Cocteau’s films. Or indeed see them for the first time: Les Parents Terribles (1948), based on his play of 1938, is often cited as his best film among cineastes, but I haven’t seen it, and it seems less celebrated – in the art world – than his Orphic trilogy.

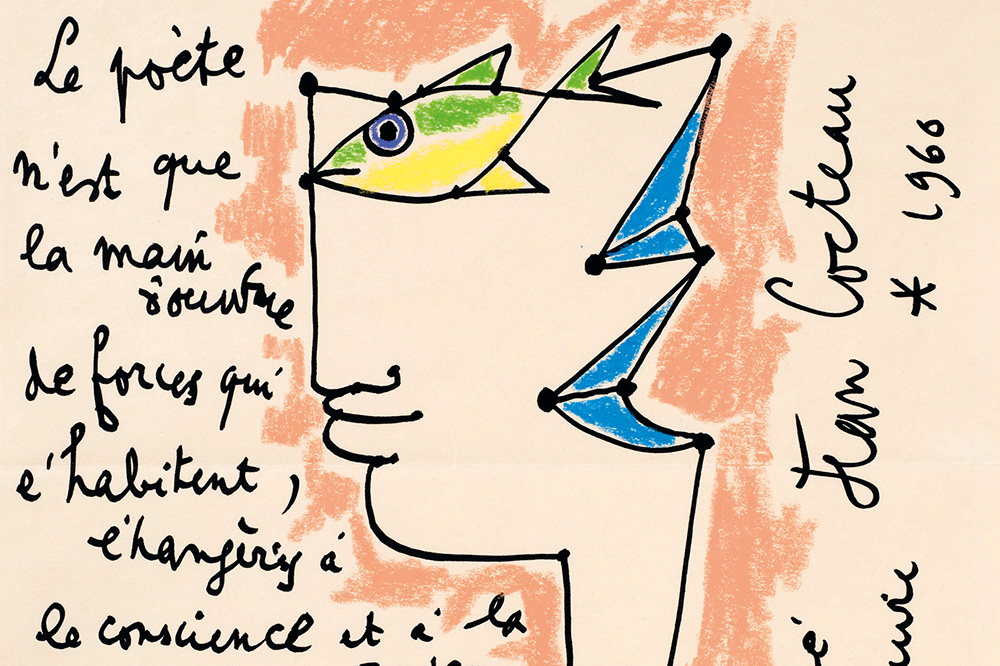

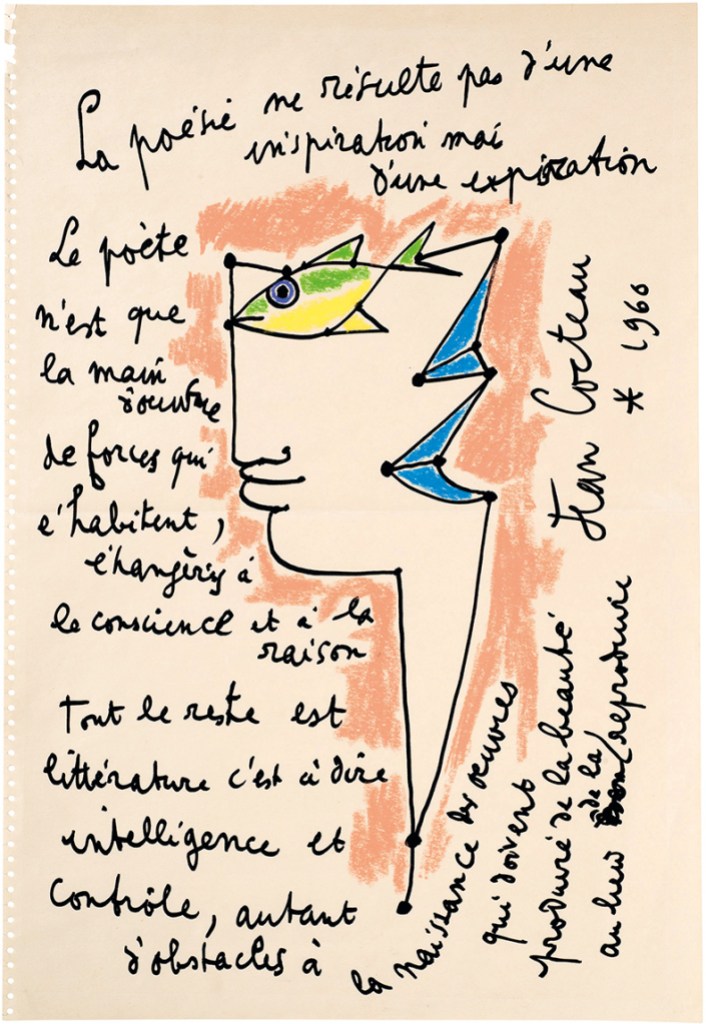

Movies transported the artist into a world beyond the Parisian avant-garde. A room of film posters, a gallery devoted to jewellery and other objets d’art that he designed, and shots of the artist cavorting with celebs (Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich, Maria Callas) are reminders of his restless promiscuity across high and low. But even in his twilight years he made wonderful drawings, including a felt-tip doodle titled Poetry (1960): an Orphic profile with a green-and-yellow fish for an eye, surrounded by a kind of manifesto: poetry does not come from inspiration, but expiration. The artist’s hand and eye were one with the poet, his body and his breath.

Orpheus’s Mirror (1960), Jean Cocteau. Collection Kontaxopoulos Prokopchuk, Brussels. © Jean Clement Eugene Mar Cocteau, by SIAE 2024

In his catalogue essay, curator Kenneth E. Silver opens with an anecdote recounted by Peggy Guggenheim in her memoirs. Planning to inaugurate her Cork Street gallery with an exhibition of Cocteau’s work in January 1938, Guggenheim plucked him from his opium-soaked apartment and took him out for dinner in a Parisian restaurant, recalling that the artist couldn’t keep his face out of a nearby mirror. Where the gallerist saw vanity, Silver senses insecurity. But perhaps something else was afoot. Sitting in a restaurant, his head abuzz with opium and the flattery of his gallerist, he perceived his reflection as a foreign object, ultimately unknowable, yet something his imagination could appropriate and use. I too exist in a hall of mirrors, he confirmed to himself.

Mirrors open the exhibition, including Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Orpheus Twice) of 1991, a pair of mirrors the dimensions of doors leaning against the wall, and Cocteau’s own Orpheus’s Mirror (1960/89), a small bronze sculpture. The wall text refers to ‘narcissistic doubling’ and the artist’s Orphic trilogy. In The Blood of a Poet, the sculpture (played by Lee Miller), roused from its ‘secular sleep’, encourages the poet to enter the mirror, which he drops into like a bath. Returning from the abyss, the poet remarks that ‘mirrors should reflect a bit more before sending back images’.

If the line surprises with its comedic tone of annoyance, as if a mirror should offer something more substantial than a fleeting reflection, the sentiment shines a light on Cocteau’s obsession with mirrors and doubling. The artist is a ‘nothing’, a collagist who redeploys a vast compendium of images, from a snippet of his visage in a Parisian restaurant to Greek myth. If his hero returned from the underworld frustrated, Cocteau was right: there is nothing beyond this existential hall of mirrors. And, like Orpheus himself, he couldn’t help but turn around to take another look.

Poetry (1960), Jean Cocteau. Collection Kontaxopoulos Prokopchuk, Brussels. © Jean Clement Eugene Mar Cocteau, by SIAE 2024

‘Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge’ is at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, until 16 September.

From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.