On 31 December 1739, Jean de Jullienne (1686–1766) was admitted to the French Academy as ‘Conseiller honoraire et Amateur’. The Academy thereby acknowledged receipt of his Recueil Jullienne, a proto-catalogue raisonné devoted to Antoine Watteau. But the distinction also formalised Jullienne’s status as a member of a particular 18th-century tribe. The ‘amateur’ was situated between the aristocratic world of the patron and the new, increasingly bourgeois, world of the collector. Though he had considered becoming an artist himself, Jullienne ultimately made his money in the family trade, cloth. It was probably around the Gobelins tapestry manufactory, where he spent much of his life, that he first came into contact with artists. He married into the upper classes in 1720, but by 1736 his business success had bought him a patent of nobility, and ‘Jean Jullienne’ acquired an aristocratic ‘de’. In placing his newly ennobled name at the centre of the Recueil, Jullienne secured everlasting fame as the most important friend of the talented, tragically departed young artist – but he also called attention to his status as the owner (and, potentially, vendor) of many of his friend’s most important paintings.

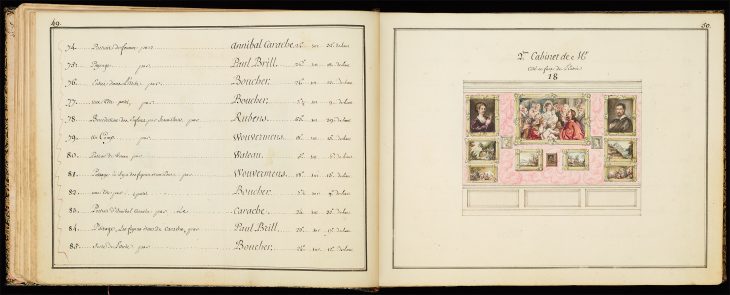

Pages 49–50, with an inventory of the ‘second cabinet’, of the Catalogue des Tableaux de Mr Jullienne (c. 1756), compiled by Jean-Baptiste-François de Montullé. Morgan Library and Museum, New York

It is possible to appreciate Jullienne’s activities as an ‘amateur’ beyond the Recueil, thanks to the Morgan Library’s digitisation of a catalogue of his art collection. Compiled in or around 1756 by his cousin, Jean-Baptiste François de Montullé, this inventory-cum-handlist is illustrated by 42 coloured plates of Jullienne’s home in Paris. It lists 367 paintings and drawings, 152 reproduced in detailed miniature watercolours, preserving a glimpse not only of the collection’s contents, but also its setting. By the standards of the time, Jullienne’s collection was comparatively open to visitors, and the catalogue, similarly, seems to have been created to a certain extent with an audience in mind. The hang is conceived with reference to the vogueish notion of the ‘trois écoles’ – art had developed in Italy and the Netherlands, whence on to the natural successor, France. Within this display are the works of the two French artists with whom Jullienne was most publicly associated: Watteau, and François Boucher, whose artistic training had largely consisted of engravings for the Recueil. They hang together in Jullienne’s ‘second cabinet’, where two Boucher heads in pastel frame a self-portrait by Watteau (now lost), alongside works by Flemish and Italian artists: Wouwermans, Rubens, Paul Bril, and Annibale Carracci. The selection of two small heads and a self-portrait suggests that, when it came to his artist friends, Jullienne preferred evidence of intimacy to ambition and range. He had once owned almost all of Watteau’s output, but the self-portrait was one of just eight pictures he retained from the days of the Recueil. It is probably not coincidental that the most significant of the others, the Fêtes Vénitiennes (now in the National Gallery of Scotland), is also thought to include a self-portrait, along with the likeness of another artist in Watteau’s circle, Nicolas Vleughels.

Detail of frontispiece of the Catalogue des Tableaux de Mr Jullienne (c. 1756), designed by Francois Boucher. Morgan Library & Museum, New York

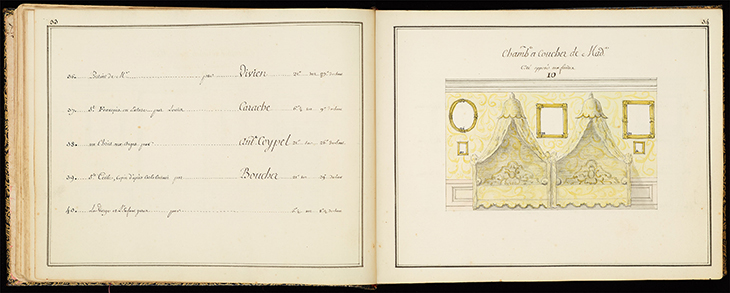

It is inevitable for lists of artworks to invite speculation about their spatial contexts, but Montullé’s catalogue is distinctive for the care it lavishes on Jullienne’s home. Architectural and decorative details receive the same treatment as works of art. Window frames, panelling, wallpaper and clocks are all faithfully rendered. Madame de Jullienne’s two single beds jut against frames representing her Carracci, her Coypel, and her Boucher. It is a reflection of the contemporary interest in the interior as a coherent decorative whole. In the catalogue’s elaborate Boucher-designed frontispiece, a group of putti (one holding a copy of the catalogue) are surrounded by pictures, but also smaller objets d’art – a Chinese buddha, a pile of shells, a nautilus – with which the easel paintings are therefore at least partially equated. It also indicates an interest in the collection as a physical experience. Several of the drawn doors remain ajar, providing vignettes into adjacent rooms whose hangs are rendered with the same exactitude as the primary paintings. As in the real house, the paintings in the painted gallery can be glimpsed from the cabinet that precedes it.

Pages 33–34, with an inventory of the the bedroom of Madame de Jullienne, of the Catalogue des Tableaux de Mr Jullienne (c. 1756), compiled by Jean-Baptiste-François de Montullé. Morgan Library and Museum, New York

For all the precision of the catalogue, it is a record of a collection almost continually in flux. Jullienne did have a paintings store, but only 12 paintings are recorded as ‘non placés’ in 1756. Yet, by the time of the legal inventory drawn up at his death in 1766, he had disposed of 30 of the works shown here, and acquired 76 new ones. The care of the catalogue may therefore reflect Jullienne’s acquisitive process. He apparently lacked the all-consuming drive to accumulate that characterises many collectors, including his friend Boucher, who bought liberally from Jullienne’s collection at its sale in 1767 (and whose own accounted for nearly 70 per cent of his estate). He seems rather to have been a careful acquirer, equally ready to sell and to buy, every object contributing to a carefully conceived and constructed whole.